The route to basic training, from Barrie, Ontario, to Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Quebec, wound coincidentally through Ormstown, where my Grandpa Thompson was buried. Dad and I stopped by after lunch at the Husky diner on the side of Highway 401, where I had a chicken club, sloppy with mayo. Dad had insisted I needed support on the drive, although it felt more like he was escorting an unruly deserter, since hed brought his own car to get himself home once the new officer cadetmewas delivered to the Forces.

Grandpa had died two years earlier, when I was sixteen, and I hadnt been to his grave since. Not much had changed about Ormstown: the streets were still haunted by clunky farm machinery; still dotted with brick houses that appeared abandoned or derelict. But Grandpa was here, in the soft ground, and I wanted to take root in the muck that sucked at my shoes, plant myself like a frothy hydrangea so that my impending military career would wither before it even sprouted.

After 9/11, Id convinced myself that the attack on the Twin Towers demanded that I carry on the Thompson military legacy, which extended back four generations on both sides of the family. Nearly two years later, the memory of a burning New York was still sharp enough to stir the patriotism Id felt when I watched the news from my grade twelve English class. Yet I was terrified, somehow already aware that military life and I werent exactly well-matched; unsure of a future with a rifle instead of a pen in my hand, because Id always thought I wanted to be a writer, never a soldier. Dangling like a carrot was the free university degree that I was two years into, paid for by the Forces, and the chance to do something that felt more important than putting my words onto the pagesomething in service of others instead of myself. Grandpawho served in the Korean War and had encouraged my stories and now lay at my feetwould have understood my uncertain reasoning. Yet for Dad, a thirty-five-year veteran, the only legitimate reason for enrolling was protecting Canada.

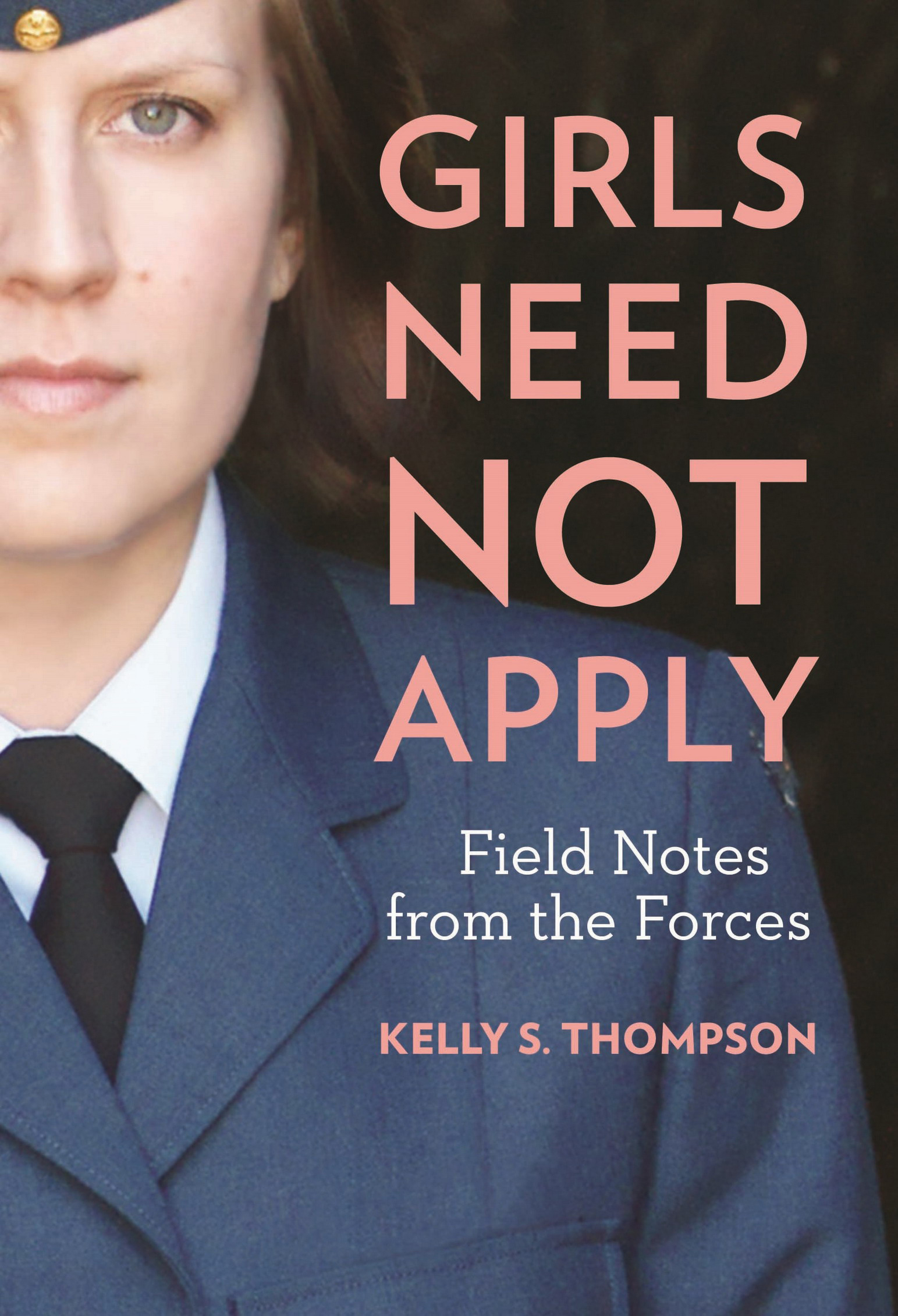

I was going to be a logistics officer in the Canadian Air Force, a fact Dad encouraged but also ribbed me for, as the air force was known as the cushier environment within the Forces. In the four generations of military Thompsons, all had been army men, enlisting in the combat arms or support trades as non-commissioned members. I was breaking pattern by being a woman, enrolling as an officer, in the air force, in a support trade with a human-resources focusa path that was more focussed on paperwork than rifles. I didnt want one of the sexy combat jobs that involved countless tours to war zones, lugging a rucksack on my back. I didnt want to have to shoot anyone, and knew my odds of having to do so would be significantly higher if I joined the army. Ultimately, I just wanted to help people in a way I saw as being suited to my personality, and in that desire I was straying from protocol, already the familys black sheep.

Dad and I stood shoulder to shoulder in front of Grandpas grave, my Volkswagen Beetle parked on the dirt road near the church cemetery behind Dads car. Even in May, the ground was soggy with moisture, my Doc Martens sinking into the earth and liquid seeping through the seams despite Dads overaggressive polishing of the toe box. His eyes were trained on the headstone as though he needed to memorize the inscription. Our family, without ever saying it, resented Grandpas burial so far from home. All of us felt aimless in our mourning without a grave nearby. But army brats have no particular origin, no one place that demands allegiance. Instead there is a series of locations, places once called home, punctuated by blurry memories no longer important. Home is wherever the family is at that moment, and so finding a final resting place might as well be done with eyes closed and a finger jabbed on a spinning globe. I shivered with the knowledge that my life would continue to follow that same wobbling path of disintegrated roots, moving every two or three years, a life of goodbyes and nice-to-meet-yous.

Whether Grandpa Thompson was in the ground beneath my feet or hovering in the air like a cartoon angel, I knew he would have been proud of me. He had been a soldier turned babysitter extraordinaire, who cared for me when Mom returned to work and my older sister Meghan was at school. Our days were filled with my stories, which he encouraged and enhanced with questions about character and plot. When storytelling was over, sometimes Id ask him to put lipstick on me, but then Id cry because he never stayed inside the lines like I was told to do in my colouring books. Other times he would pop his dentures out of his mouth and drop them in my hand, still warm and full of saliva, insisting only I knew how to brush them properly. On nice days, I would zip around the driveway on my bike while he chain-smoked from a plastic lawn chair on the porch. I lived for his approval, which he gave steadily and assuredly. With him I didnt feel the usual pang of anxiety rising from deep in my stomach. By contrast, Grandpa-less nights were spent nibbling on my cuticles (which I feared made me a cannibal, a word Id looked up in my parents large dictionary), and then worrying about the fact that I was worrying. Nerves were in my genesanother generational traitbut those before me had proven that anxiety could be overcome.