To Elise

CONTENTS

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

________________________________

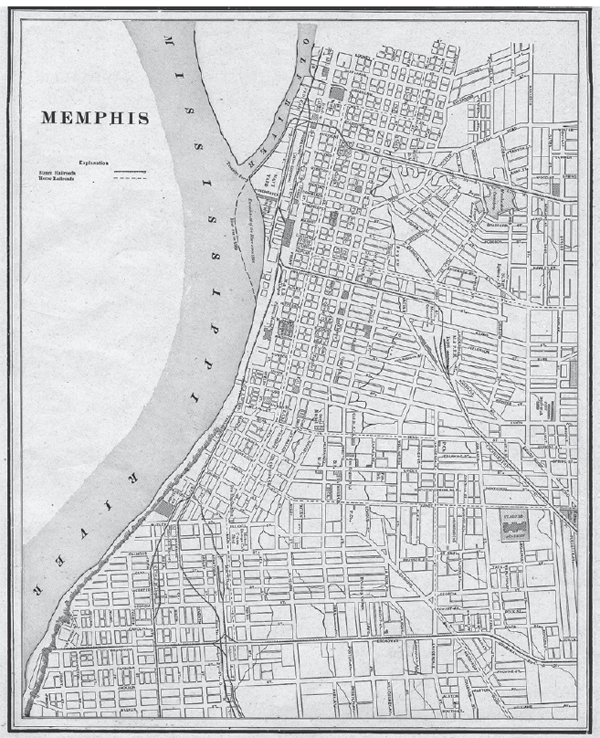

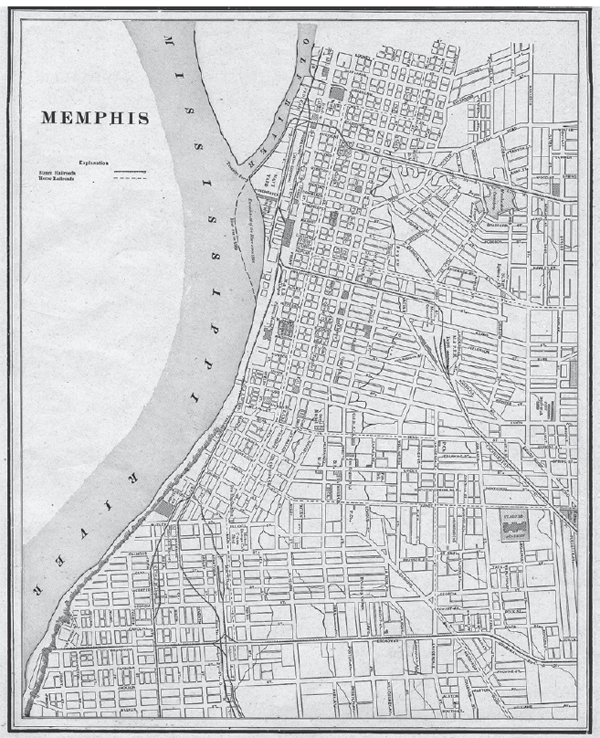

Memphis in 1901.

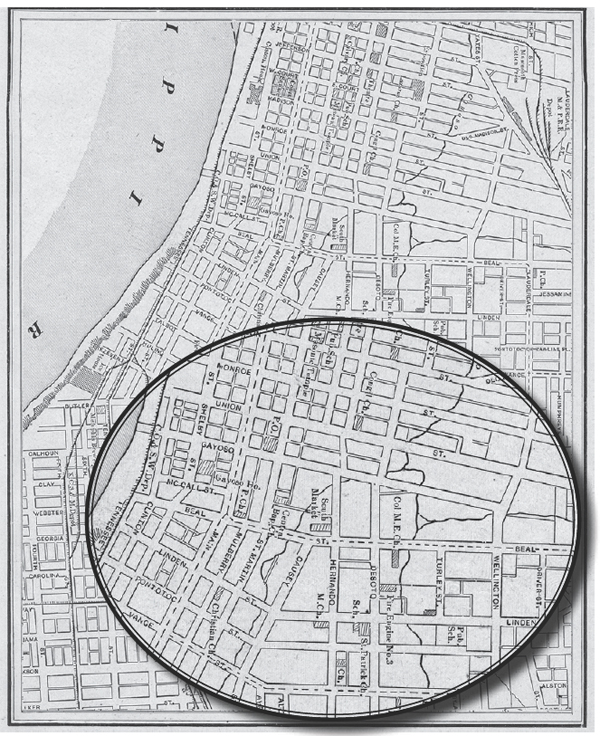

Downtown Memphis, 1901. Inset: Beale Street District.

BEALE STREET DYNASTY

JUNE 6, 1862,

DAWN ON THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER

AT MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE

Artillery thunder ricocheted over the river, jolting the crew of the Victoria . She was an eight-hundred-ton paddle-wheel steamer, at the moment employed for the cause of the Confederacy as a blockade-runner, shuttling supplies between her home port of Memphis and New Orleans.

Captain and crew gathered on deck to watch the five Yankee gunboats and two ironclad rams meet a rebel fleet of eight river steamboats armored haphazardly with scrap metal.

One of the Victoria s cabin boys bore the captains name and likeness. Robert Church was twenty-three years old. He belonged to his father not only as a son but as a slave. Captain took care of him, though, and Robert had enjoyed as adventurous and free an upbringing as was available to anyone, much less a Negro, in nineteenth-century America. Capt. Charles Church had instilled in his son a degree of personal pride, telling him, Dont let anyone call you nigger.

River life gave an outlet to Roberts courage and wit and provided him an education unlike anything most slaves could comprehend. He had survived disaster, like the fiery sinking of his fathers steamboat the Bulletin No. 2 in 1855. He studied rich white planters and blackleg gamblers at leisure. He procured their whiskey, attended their card games, and learned their thirsts.

The Mississippi cultivated some of the elite black men of the nineteenth century, and Robert Church came of age with Blanche K. Bruce, a future U.S. senator from Mississippi, and P.B.S. Pinchback, who would become the nations first African-American governor, serving Louisiana. These leaders grew familiar with the feeling of cash and coin in their pockets, and they would be noted for their craftiness and flash.

Now the gunboats flying Old Glory overtook the rebel ironcladsand presented Robert a dilemma. He could either stay with the Victoria and await Federal captureand possible liberation from slaveryor risk his life swimming to the Confederate shore.

As the story goes splash!

Sloshing through the water, he couldnt have known that hed safely make it ashore, much less that he would grow there into something the world had never seen, that he would reach a yet-incomprehensible status: the Souths first black millionaire.

Even more improbable is how he would do it. Like many a great and wealthy man, Robert Church was also compromised. He courageously built a fortune through taking unbelievable personal risks, for while black men across the South were being hanged and burned alive for committing alleged and unproven offenses against white women, Church became the wealthiest black man in the South due in large part to his whorehouses that employed white women.

He built not only a fortune but a civilization around himself.

This is the story of how a slave became an emperor and of the dynasty Robert Church created. Though he founded it on debauchery, he ran his kingdom with sensitivity to virtue. He helped support both Ida B. Wells, as she developed into a radical civil rights journalist, and W. C. Handy, as he laid the foundation of American popular music. The Church dynasty evolved from a red-light real estate empire into the most powerful black political organization of the early twentieth century.

Beale Street ranks as the dynastys crowning achievement. Thanks in large part to Robert Churchs audacity, vision, and acumen, Beale became the Main Street of Black America, a site of monumental innovations, thrilling promise, and devastating tragedy that wrote the headlines, played the soundtrack, and forged the secret history of an era, unmatched in prowess by any three-block stretch in the land.

Beale was both of America and exceptional. Entertainer Rufus Thomas, a Memphis mainstay from the 1930s to his death in 2001, said, I told a white fellow... If you were black for one Saturday night on Beale Street, you would never want to be white anymore.

In a climactic struggle, Beale Street also fueled the powers that would destroy Robert Churchs legacy. But before Church could build a dynasty, he had to make himself.

BIRTH OF

A KINGPIN,

18661885

I wonder why they gave it

such a name of old renown;

This dreary, dismal, muddy,

melancholy town.

W. H. RUSSELL

THERE IS

NO YANKEE DOODLE

IN MEMPHIS

SPRING 1866, MEMPHIS

A lone mule pulled the streetcar down Main. People on foot, on horseback, or in buggies, and hacks and drays of cotton and lumber wore the cobblestones slippery and black. The street shot southward toward the fort. Five solid blocks of brick buildings had lately grown up here, some as high as five stories.

Past Beale Street, Mains cobbles turned to dust, and brick buildings shrank to whitewashed log shanties. The change and its suddenness, in the half-dozen blocks from the heart of town down to South Street, felt like a jump from eastern metropolis to western frontier.

The trouble started down this way.

Blue-coated Negro soldiers from Fort Pickering congregated in the rough-built groceries and makeshift cabins, drinking and firing their pistols on Gradys Hill.

At the last stop before unyielding darkness stood a large rambling frame structure, set on a huge yard with a few small sheds and dwellings scattered around. Here a white woman named Mary Grady ran a Negro dance hall and served drinkswine, soda water, brandy peaches, and such as you would find in any little shebang, she would say. Here the disturbances grew louder every night of April 1866. As Gen. George Stoneman, commanding officer at Fort Pickering, the garrison at Memphis, later explained, These soldiers, inflamed with liquor, coming and going from this house, were in the habit of firing their pistols promiscuously, in all directions, endangering the safety of my command.

Though Memphis had emerged from the Civil War physically intact, forces were converging to make the city a key battleground in the next phase of national conflict. Just over a year after Gen. Lees surrender, Memphis told the country that reconciliation would be even more vicious and bloody than anyone had feared.

Memphis had sprouted from one of the few sites along the Mississippi River that could accommodate a metropolis. With the Chickasaw Bluffs protecting it from annual floodingand providing Memphiss distinctive moniker, the Bluff Cityits location on the river guaranteed prominence in the national flow of goods to market, as did its proximity to potentially millions of acres of cotton. In 1857 the Memphis-Charleston Railroad had opened the first route from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean across the South, establishing a route between a large East Coast slave market and the envisioned inland cotton empire. A Confederate triumph might have made Memphis one of the more prominent cities on the continent.

Next page