Contents

Guide

ALSO BY DALE COCKRELL

Demons of Disorder:

Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World

The Ingalls Wilder Family Songbook (editor)

Excelsior: Journals of the Hutchinson Family Singers, 18421846 (editor)

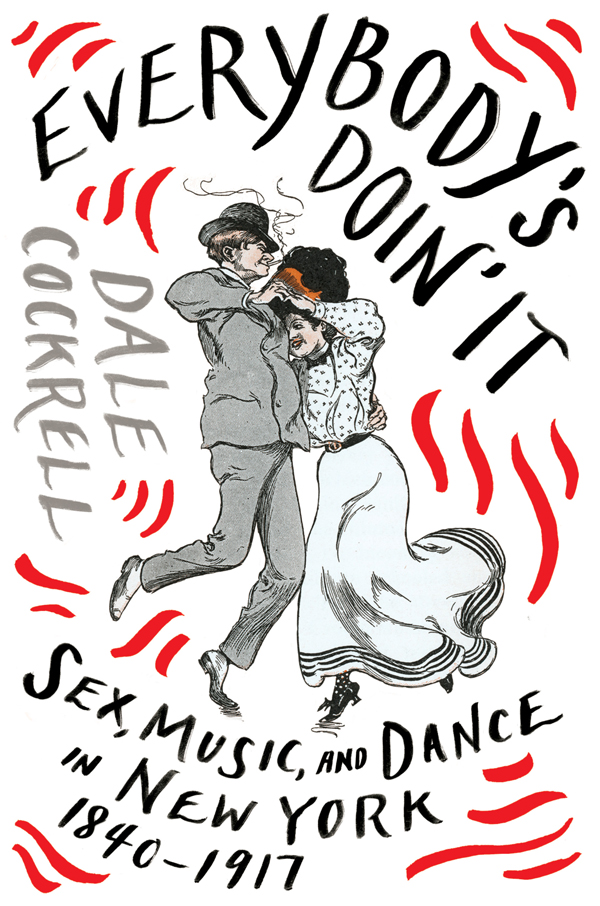

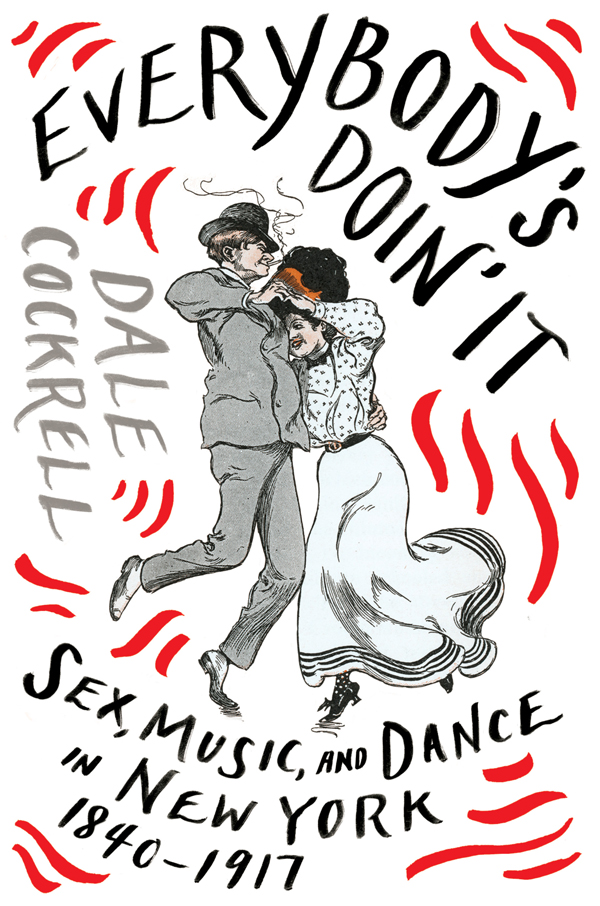

EVERYBODYS DOIN IT

Sex, Music, and Dance in New York, 18401917

DALE COCKRELL

W. W. Norton & Company

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York  London

London

Copyright 2019 by Dale Cockrell

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at

specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Dana Sloan

Production manager: Anna Oler

Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Cockrell, Dale, author.

Title: Everybodys doin it : sex, music, and dance in New York, 18401917 / Dale Cockrell.

Description: First edition. | New York : W. W. Norton & Company, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019000965 | ISBN 9780393608946 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Popular musicNew York (State)New YorkTo 1901History and criticism. | Popular musicNew York (State)New York19011910History and criticism. | Popular musicNew York (State)New York19111920History and criticism. | Popular musicSocial aspectsNew York (State)New YorkHistory.

Classification: LCC ML3477.8.N48 C63 2019 |

DDC 781.6409747/109034dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019000965

ISBN 9780393608953 (eBook)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

Dedicated to the untold thousands of women upon whose anonymous bodies an American music was built.

We must never forget.

CONTENTS

But I must have said this before, since I say it now. I have to speak in a certain way, with warmth perhaps, all is possible, first of the creature I am not, as if I were he, and then, as if I were he, of the creature I am.

SAMUEL BECKETT

E VERYBODYS D OIN I T began, as has so much in my scholarly life, while I was enfolded in the majestic silence of the American Antiquarian Societys Reading Room. The National Endowment for the Humanities had awarded me a research fellowship in the mid-1990s to complete work on what became Demons of Disorder: Early Blackface Minstrels and Their World , and I was joyously working my way through the rich resources of the AAS. During my intellectual journey there I first started to glimpse with some modest clarity the relationship between Jacksonian-Era people who inhabited New Yorks working-class neighborhoods and those who practiced the music of early blackface minstrelsy. Both groups were frequently charged with being disorderly, a term with legal and social (and musical) implications. Legally, then as still today, the term meant immoral or indecent conduct; socially, Noah Webster in that time defined disorderly as contrary to rules or established institutions. The implied opposition in both casesorderwas owned by those in power, and, without subversion through disorderly behavior and disorderly music, lower-class people were trapped at the bottom of an imposed, orderly world.

At some point in my work, I peered far ahead from Demons to the development of early jazz and wondered about a hypothetical connection between that disorderly point in time and space, with its resulting riotous music, and Jacksonian disorder and its brand of riotous music. This book follows from that moment of reflection, an effort to connect some of the dots between the 1840s, when Demons of Disorder left off, and 1917, when jazz hit America.

Many of the same obstacles confronted in Demons of Disorder stood in the way of Everybodys Doin It , as did some of the same research strategies I employed to overcome them. Since civil authorities tended to take special note of disorder and attempt to do something about it, my attention has frequently been drawn toward laws, legal matters, police and court records, chronicles of alleged illegalities, newspapers, and the records of organizations devoted to social reforms. In such documents are often found accounts of the disorderly and their behaviors, if not the inner realities of their lives.

In general, my people (for I have come to love and admire them) tended to live below what I called in Demons of Disorder the horizon of record. To many of these people, the spoken word weighed more than the written, for they were an oral lot. Narratives were vaporous, and of the moment. Then, too, it is in the very nature of documents and artifacts that they tend to be preserved in a ratio commensurate with the social standing of the subject; archives are seldom maintained for those of low social class. In order to reconstruct the lives of the working-class actors in this book, I have often had to rely on the words of literate middle-class witnesses who, as a group, condescended to those beneath their place. It is likely that their biases are embedded in their accounts. Given that, one should be suspicious, as I have tried to be, of many of my sources historical accuracy. As a rule of thumb, disparaging views written by urban middle-class reporters about the urban hoi polloi should probably be dialed back a notch or two, sometimes even more. Stilland importantlyenough common ranting across a body of narratives likely indicates some underlying truth.

Disorder has often been employed as a code word for prostitution, a social issue writ large in Demons of Disorder , as, of course, in this book too. In fact, when I began the research for Everybodys Doin It , I imagined a book that would be a comprehensive treatment of the demimondes role in the development of American music and dance. I learned, without much effort and contrary to much commonly held wisdom, that prostitution was a large, highly developed urban industry throughout the United States from the Jacksonian Era up to World War I. Furthermore, there was a mountain of documentation (some forty-three, city-commissioned vice reports from across the nation, for example), and I laid plans to climb it. In a pivotal conversation with Wendy Strothman, my agent, she suggested that I focus this book only on New York City. The logic was immediately compelling; I did not require much convincing; and the weight of the world lifted. But I still glance occasionally over more-relaxed shoulders and glimpse yet-unwritten books, articles, and dissertations on sex, music, and dance outside of New York (and some still on sex, music, and dance in New York), for it turns out that its a very big subject. If only the shuffle dance with this mortal coil werent so damned insistent!

A word on words. What are today acknowledged as highly derisive, deeply pejorative, bluntly racist terms were commonly used and printed in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America. Some of these show up here embedded in quotations. Their usage is a form of historical evidence and I have reproduced them as written, but always with a flinch and a silent mark of anachronistic condemnation. Outside of quoted material I have generally opted to use black when referring to African Americans, for it was a relatively benign word in common usage during the period of this study and remains so today.

London

London