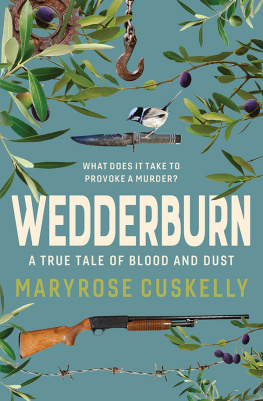

Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

First published in 2018

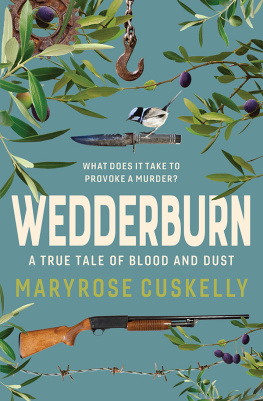

Copyright Maryrose Cuskelly 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76052 807 2

eISBN 978 1 76063 759 0

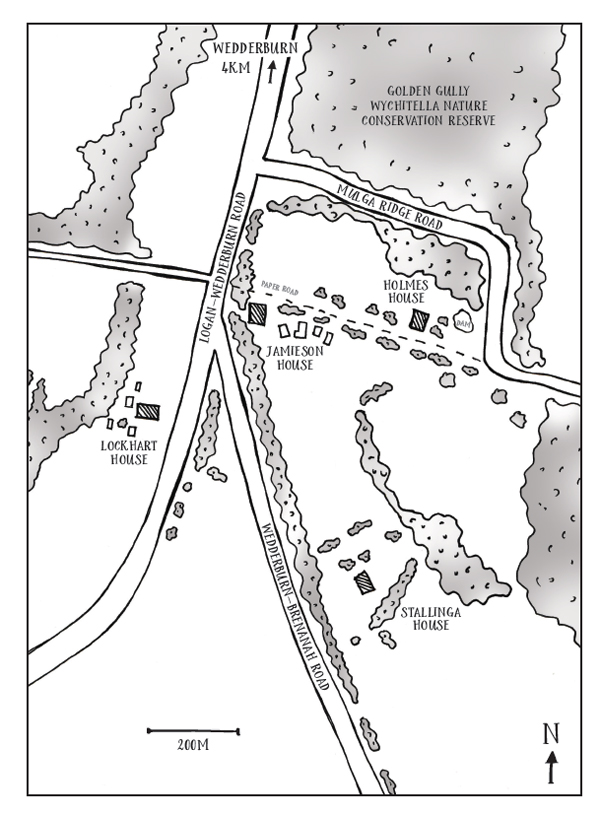

Map by Christa Moffitt

Set by Bookhouse, Sydney

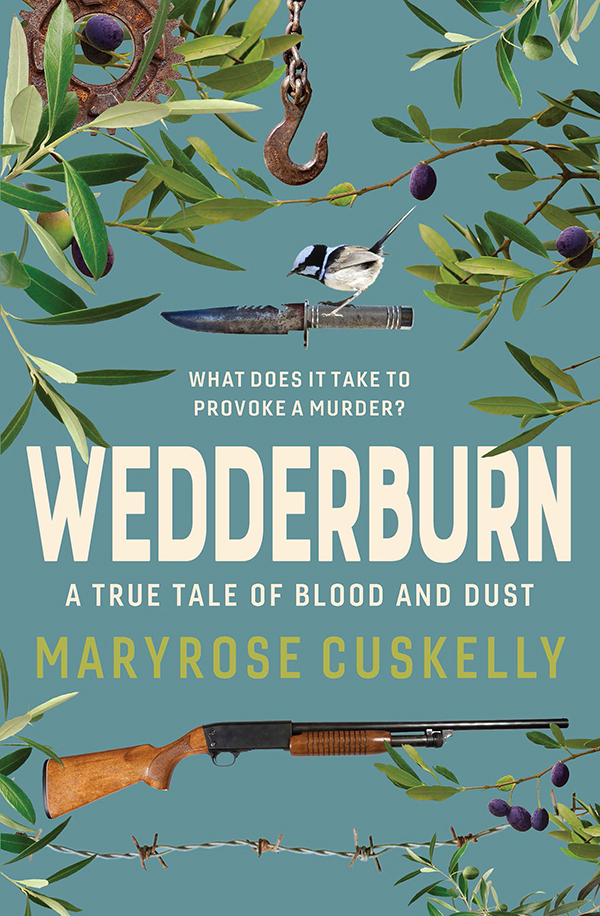

Cover design: Christabella Designs

Cover photos: Shutterstock

In memory of Peter Lockhart, Mary Lockhart

and Gregory Holmes,

and for all those left broken-hearted

That is what is so convenient in tragedy. The least little turn of the wrist will do the job.

Anything will set it going

Jean Anouilh, Antigone

The littlest thing can cause a fallout.

Gavan Holt, Councillor for Wedderburn Ward, Loddon Shire

The first account I heard of the killings had the logic and trajectory of a fairy tale. Not a Disneyfied souffl of princesses in citrusy pastels, but a grisly fable such as might have been told by the Brothers Grimm. Essentially it centred around an uncomplicated plot, set in train by conflict impelled by the actions of archetypal characters and climaxing in a scene of cathartic violence.

Foremost among the slain was a tyrant, feared and hated, then the tyrants weak wife and her warrior son. The latter had recently returned from battle, wild and strange from the things he had seen and done. There were even hints of a stepdaughter imprisoned against her will, who fled under the protection of the man who would become her husband. Then there was the stern loner, who dispensed harsh justice to the tyrant and his family in an act of righteous vengeance. Finally, there was the village, freed from the yoke of the tyrants malignant presence.

Of course, the reality was neither so neat nor so simple. The protagonists were not archetypes, but complex and flawed human beings, whose motivations were clouded, and whose state of mind was contested by those who knew them. What was clear was the scale of the violence and the blast-like devastation of its fallout. The slaughter was extravagant and bloody. The grief and horror of the victims family and those close to them were profound, their lives blighted by the knowledge of what had been done to their loved ones. And yet there were people in the small town of Wedderburn in Central Victoria who, while they did not exactly rejoice, quietly thought that Ian Jamieson, who murdered his three neighbours one night in October 2014, had done them all a favour.

When I first began to probe into the killing of Peter Lockhart, his wife Mary and her son Gregory Holmes, I did so with little more than curiosity as to where the story might lead and what it might reveal.

There were the murders themselves, obviously, and how they unfolded. But after I read the first scant reports that a feud fuelled by dust was behind the violence, the crime itself was the thing of least interest to me. I was more intrigued by questions relating to the community in which it happened; the relationships between all of those involved; and what could lead a person, over months and years, seemingly inexorably, to the point where they could commit such an act.

Inevitably, my view of the murders and the protagonists was framed by the perspectives of those I first spoke to about them. Aspects of the killings that were told to methe events that were known to precede them; the nature and character of the protagonists; and the communitys response to the slayingwere relayed in such a way that at first I wondered if this story posed the question if it is ever justifiable to kill a bad man. What could be behind the rumours I heard that at least some of those living in the community viewed the killings, in particular the murder of Peter Lockhart, as an understandable reaction to extreme provocation? How could anyone, apart from the most callous individual, describe the killing of another person as a favour?

These and other questions kept me going back to Wedderburntalking to one person and then another, walking its wide, country-town streets, and then attending the court proceedings concerned with the charges against Ian Jamieson. As I did, the story kept opening out like a chatterboxa folded-paper fortune teller that I used to make as a kidevery choice unfurling to reveal more possibilities to explore beneath. I did this for months before committing to writing a book about the murders. There was a story here, but it was not initially apparent to me what, at its heart, it was about.

As I spent the next two and a half years researching and writing, I came to see, of course, that this was not a story about one thing but about many things: violence, masculinity, families, the judicial process, the life of small communities, and the pull and sweep of emotions and human qualities, both base and lofty. And in coming to know, a little, those caught up in the sorrow and disruption generated by the deaths of Peter and Mary and Greg, my detachment began to leach away.

The triple zero operator asks him if anyone needs an ambulance.

No. I think theyre past that. I took their heads off.

The police were at his neighbours place earlier and would have already found the body of the younger bloke, he tells the operator. If they went to the house across the road theyd find the other two.

They just push people, the operator overhears him saying, presumably to his wife. They dont know when to give up, these cunts.

It is hot for spring and the rainfall for October is tracking well below average, as it has been for the past several months. In fact, the whole district has been in drought for almost two years. The paddocks are parched and the roads are dusty. Everything is dusty.

By mid-afternoon on Wednesday 22 October 2014, the temperature has reached 33C. At around two-thirty, 64-year-old Ian Jamieson and his wife, Janice, return to their house on the LoganWedderburn Road from a hospital appointment in Bendigo, a one-hour drive away. Janice has been ill and, while she and her husband are separated, she sometimes stays with Ian at the home they once shared.

Shortly before four-thirty, Peter Lockhart drives his yellow Kubota tractor along the dirt track that runs beside Jamiesons boundary fence. The fence separates the property belonging to Greg Holmes, Lockharts stepson, from Jamiesons place. The track, which lies on Holmess side of the fence, is a paper road: a surveyed but unsealed right of way.