Table of Contents

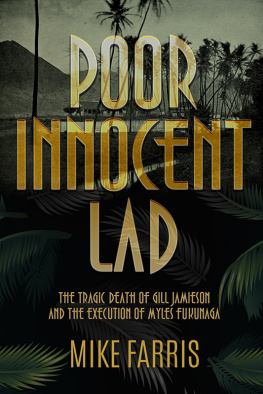

Poor Innocent Lad: The Tragic Death of Gill Jamieson and the Execution of Myles Fukunaga

By Mike Farris

Copyright 2018 by Mike Farris

Cover Copyright 2018 by Untreed Reads Publishing

Cover Design by Ginny Glass

The author is hereby established as the sole holder of the copyright. Either the publisher (Untreed Reads) or author may enforce copyrights to the fullest extent.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher or author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If youre reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to your ebook retailer and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Also by Mike Farris and Untreed Reads Publishing

Wrongful Termination

www.untreedreads.com

Dedication

To Susan: Ive said it before and Ill say it againAloha nui loa.

Acknowledgments

When you write a novel, you get to simply make up stuff. But when youre writing nonfiction, especially a story that happened nearly 90 years ago, one of the hardest things is to gather the historical records of the events youre writing about. After all, accuracy is paramount to nonfiction. I owe thanks to a number of people and institutions for helping me gather the records for Poor Innocent Lad. They either obtained documents for me or pointed me in the right direction, and I could not have done this without them, and I owe them my thanks and gratitude.

Because this is a true story, involving real people, I have tried to be consistent with the historical record, particularly when quoting directly from transcripts and newspaper articles or setting out statements and transcriptions exactly as they appeared in the original documents. Doing so may result in apparent typographical errors or seeming inconsistencies or, on occasion, raising unanswered questions. I hope this doesnt create any confusion, but I felt duty-bound to honor the original record.

Kathryn Kat Arinaga in the Hawaii & Pacific Section of the Hawaii State Library was invaluable in providing dozens of contemporaneous news accounts from the Honolulu Star-Bulletin and the Honolulu Advertiser, as well as other media outlets from the time. Ju Sun Yi and Troy Kimura at the Hawaii State Archives also provided hard-to-find documents.

When I thought I had hit a brick wall tracking down the trial transcript of the criminal case of Territory of Hawaii v. Fukunaga, it occurred to me that, since the defense attorneys had appealed the conviction to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, they would of necessity have filed the transcript there as part of the appeal. Lisa Larribeau at the Library and Research Services for the Courts of the Ninth Circuit directed me to the National Archives, where records from that far back were archived, and to the Gallagher Law Library at the University of Washington, where others were archived. Charles Miller, an archives specialist at the National Archives at San Francisco was able to locate and send me the transcript, while Caitlyn Stephens at the Gallagher Law Library provided copies of the appellate briefs.

Alyson Helwagen, publisher of Honolulu Magazine, and Mike Keany, executive editor, provided articles that I never thought I would find, and DeSoto Brown at the Bishop Museum did as well.

I also owe a debt of gratitude to my agent, Donna Eastman, and the fine folks at Untreed Reads, including Jay Hartman and K.D. Sullivan, for their efforts in gettig this book out to the public. I had two readers I relied heavily upon for feedback. One is Susan Heygood McCoy, who provided invaluable input and discussion, and I will be forever grateful for her help.

The other, last but certainly not least, is my long-suffering wife, Susan, who read and reread the manuscript nearly as many times as I did, and who had to listen to me obsess over the book every step of the way.

As they say, it takes a village.

Introduction

Mas. Gill Jamieson, poor innocent lad, has departed for the Unknown, a forlorn Walking Shadow in the Great Beyond, where we all go to when the time comes.

Those words, printed in a handwritten letter delivered to the Honolulu Star-Bulletin on the morning of September 20, 1928, told the city of Honolulu that 10-year-old Gill Jamieson, the only son of Hawaiian Trust Company vice president Frederick Jamieson, was dead. What had begun as the search for a kidnap victim quickly turned into a search for Gills bodyand for his unlikely killer, a 19-year-old Japanese man named Myles Fukunaga. Within a space of three weeks from the date of Gills murder, Myles was arrested, confessed, was tried, convicted, and sentenced to death. An open-and-shut case.

Or was it?

I first learned about this story while working on my book A Death in the Islands: The Unwritten Law and the Last Trial of Clarence Darrow. Attorney Robert Murakami represented David Takai in the notorious Ala Moana/Massie case discussed in that book, in which five young men were unjustly accused, in 1931 Honolulu, of raping a woman named Thalia Massie, wife of naval lieutenant Thomas Massie. While researching Murakami, I discovered a fascinating book called Jan Ken Po: The World of Hawaiis Japanese Americans (University of Hawaii Press, 1973) by Dennis M. Ogawa. Chapter 6 of that book, entitled Reaping the Whirlwind, told the story of the tragic death of Gill Jamieson and the execution of Myles Fukunaga, and piqued my interest.

I also quickly learned, as I dug into it a bit more, that there was a tremendous overlap in the historical figures who factored in both cases. Besides Murakami, Judge Alva Steadman, who presided over the Fukunaga trial, and who sentenced him to death, also presided over the Ala Moana case. Judge Albert Cristy, who denied a motion for new trial filed by Fukunagas attorneys, presided over the grand jury that indicted the defendants in the Massie case. City and County Attorney Charles S. Davis prosecuted the case against Fukunaga, and later replaced Judge Cristy as the trial judge in the Massie case. Attorney William Heen assisted in police interrogations of Fukunaga, and also owned the home that was rented by the Fukunaga family. In the Ala Moana case, he represented defendants Ben Ahakuelo and Henry Chang. Attorney Eugene Beebe, who assisted the prosecution, behind the scenes, of the Ala Moana defendants, and who is credited with planting the idea to kidnap Joe Kahahawai in the mind of Tommie Massie, was appointed as defense counsel by Judge Davis to represent Myles Fukunaga in his murder trial.

And in a particularly interesting coincidence, the family of Gill Jamieson resided at 2751 Kahawai Street in the Manoa section of Honolulu, while Tommy and Thalia Massie later resided just a block away at 2850 Kahawai Street.

In the Reaping the Whirlwind chapter of Jan Ken Po, Dennis Ogawa described what appeared to be an open-and-shut case of abduction/murder in which the right man justly went to the gallows. But I sensed that there was more to the story. The conviction and execution of Myles Fukunaga touched off a furor of racial antagonism in Hawaii, particularly involving the Japanese community, which made up in excess of 40% of Hawaiis population in the late 1920s. The prevailing feeling among the Japanese was that the speed with which Myles was tried and convicted15 days from arrest to pronouncement of the death sentenceand the unwillingness to concede that Myles may have been insane, were driven by his race.