Contents

Guide

The patients named here were identified in the news media at the time, together with their progress. Those who were not identified publicly are referred to only by first names, which have been changed, as have their physical characteristics. Names and physical characteristics have also been changed by others who are identified only by their first names.

To my daughters,

Alexandra and Victoria.

I warn you to travel in the middle course, Icarus, if too low the waves may weigh down your wings, if you fly too high the fires will scorch your wings. Stay between both.

Ovid

Close to the Sun

Copyright 2019 by Stuart Jamieson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used

or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or

mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval

systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

For information, please contact RosettaBooks at

, or by mail at

125 Park Ave., 25 th Floor, New York, NY 10017

First edition published 2019 by RosettaBooks

Interior photographs come from the personal archive of the author.

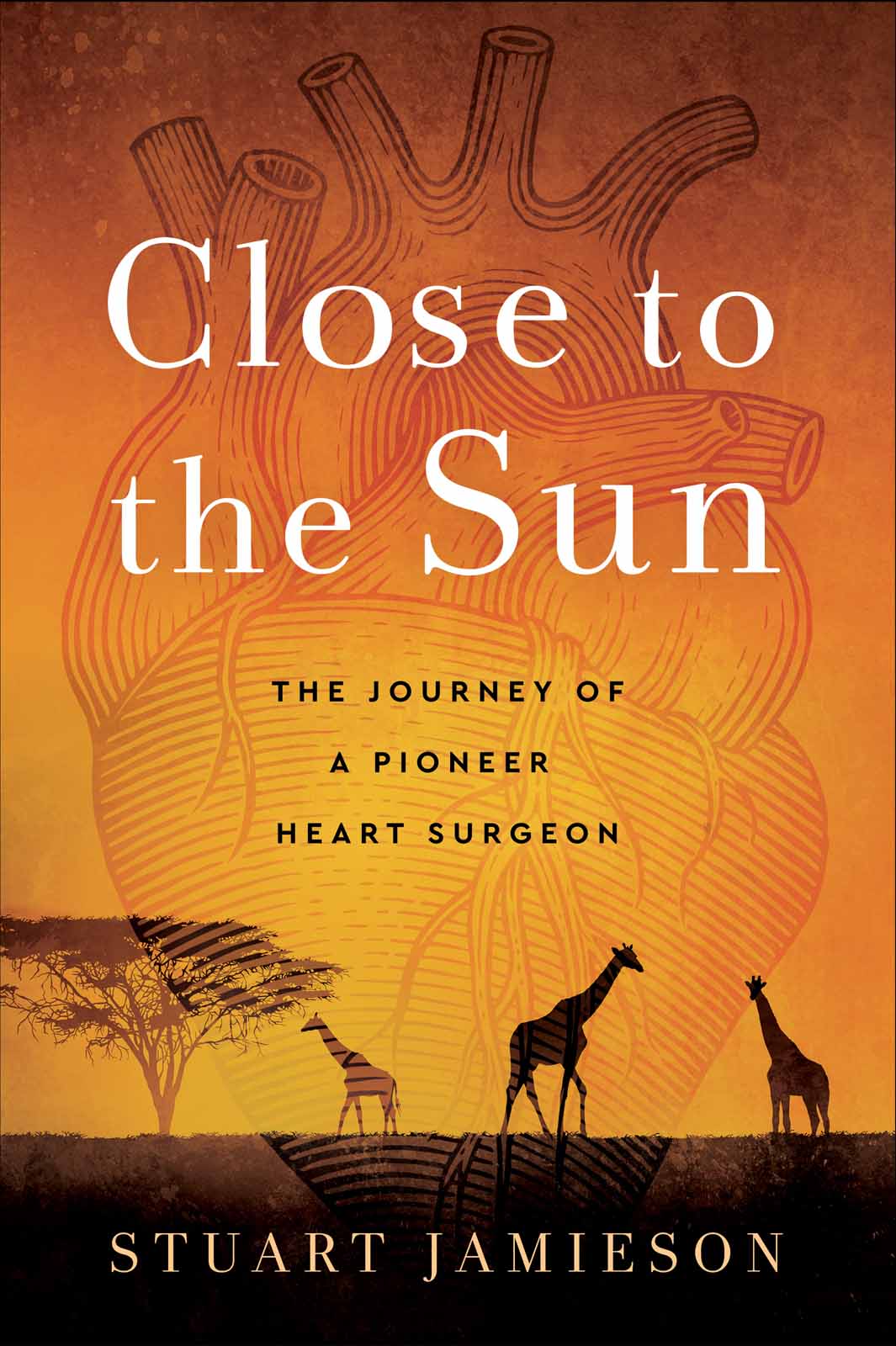

Cover design by Mimi Bark

Interior design by Alexia Garaventa

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018950744

ISBN-13 (print): 978-1-9481-2232-0

www.RosettaBooks.com

Printed in the United States of America

Foreword

One of the most significant scientific advances of the past century is the ability to perform surgery on the human heart. Cardiac surgery ranks in importance with space travel, computers, antibiotics, control of communicable diseases, and other major breakthroughs made during the twentieth century.

In his memoir, Dr. Stuart Jamieson presents a vivid account of his experiences as a member of the so-called second generation of cardiothoracic surgical pioneers. In a highly engaging and readable manner, he describes the background and formative influences that led him to choose a surgical career. Like many other creative individuals, he had a fascinating early life that did not necessarily prepare him for his later professional accomplishments. Of particular interest are the stories he tells about the adventures he experienced during his developmental years in southern Africa.

Dr. Jamiesons surgical career was marked by a new, aggressive approach to the treatment of cardiopulmonary disease. Because of his interest in heart and lung transplantation, he helped introduce many technical modifications in these procedures. He also helped pioneer strategies for overcoming tissue rejection, which had previously impeded favorable long-term outcomes. One of the most important breakthroughs to which he contributed was the early use of the immunosuppressant drug cyclosporin, which substantially improved the results of transplant procedures. Perhaps the most significant of his many accomplishments, however, is the operative procedure he devised to solve the difficult problem of pulmonary embolism. That operation is among the most challenging and complex of all cardiopulmonary procedures. His results with it are unequaled.

This book includes intimate insights into the lives of pioneers in heart surgery and transplantation, weaving the history of heart and lung surgery into Dr. Jamiesons own history. With its generous illustrations and human interest stories about both patients and physicians, Close to the Sun should appeal to medical professionals and the general public alike. Complex medical situations have been made easily understandable to laypersons.

On a personal note, I recall being asked many years ago by the British Heart Association to give an invited lecture at the Brompton Hospital. Arriving at Heathrow Airport, I was met by a bright young surgeon who introduced himself as Stuart Jamieson. He was then a registrar at the Brompton Hospital and had been assigned to escort me during my visit. We enjoyed the first of many enjoyable conversations. I was impressed by him at the time, and that excellent impression has continued over the years. I am proud of our friendship.

Denton A. Cooley, MD

Founder and president emeritus

Texas Heart Institute

Houston, Texas

PART ONE

AFRICA

CHAPTER ONE

STARTING OVER

T he plane from Cape Town was crowded. Most of the passengers were white and appeared well-off, dressed in crisp khaki and headed home from shopping in South Africa for the essentials they could no longer find in Zimbabwe. Id heard that in the years since the civil war had toppled white rule in the country formerly known as Rhodesia, it had become nearly impossible to buy anything that wasnt made there. Now a trip to the store for toothpaste required international travel. We flew over dusty plains and bouldered outcroppings. As the plane traveled into Zimbabwe and made its descent, I saw that the airport at Bulawayo, which I remembered as a grand place, was little more than a crumbling airstrip in the middle of a scrubby field. We landed, pulled up to the terminal, and got off at Gate 5an amusing conceit, as it was the only gate. Inside I noticed a few game heads on the walls, forlorn reminders of a different time.

The lines in the immigration area were long and slow. The thump of papers and passports being stamped echoed monotonously. When I at last reached the front, I handed my passport to a young black officer in a starched uniform. He looked at it for a long moment and then up at me.

You were born here, in Bulawayo? he asked.

Yes, I answered.

Welcome back, sir, he said, stamping my passport and waving the next in line forward.

I rented a car and drove through town, which took only a few minutes. After thirty years, everything looked familiar but in disrepair. The streets were crowded with people. AIDS had begun its hollowing out of the population, and nearly everyone I saw was either young or old. There was nobody in between, and nobody seemed to have anything to do. A little beyond the edge of town opposite the airport, I came to our old house. It looked more or less as it had, though it was now surrounded by a high wall. A steel gate guarded the entrance to the driveway. A sign of different times. As I looked the place over, two young boys tore around the property on small motorbikes. I remembered how my father often spent his weekends perched on a low stool weeding the lawn, looking smart in his bush hat and listening to the cricket matches on a transistor radio. Presently, a Mercedes swept up to the gate. An impatient-looking white woman honked the horn, and a gardener ran over to let her in before going back to his watering.

I headed for Whitestone, the boarding school I had gone off to as a young boy. The dirt road was now tarred, and houses stood in rows on either side where the bush had once crowded in. There were children in the schoolyard, both black and white. This Id expected, though the fact that half were girls brought me up short. Whitestone had been a boys school in the grim English tradition when Id attended, run by incompetent instructors whose ignorance and cruelty were thought to be the best sort of influence on the leaders of the future. This had been a torture then reserved for whites only. Id hated every minute of it. The students no longer wore khaki but were now smartly turned out in crimson jackets with a bird embroidered on the front pocket. The school itself appeared little changed. I ruefully contemplated the motto over the door: Veritas Omnia Vincit. Truth conquers all. Its a concept thats easy to believe until youve lived long enough to see through it.