This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781407027166

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

First Published in New Zealand by Awa Press in 2007

This edition published in 2009

by Ebury Press, an imprint of Ebury Publishing

A Random House Group Company

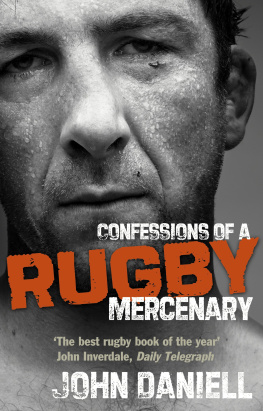

Copyright John Daniell 2007

Epilogue copyright John Daniell 2009

John Daniell has asserted his right to be identified as the author of thisWork in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

Addresses for companies within the Random House Groupcan be found at www.randomhouse.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781407027166

Version 1.0

To buy books by your favourite authors and register for offers visitwww.rbooks.co.uk

First edition published in 2007 by Awa Press16 Walter Street, Wellington, New Zealand.

| Agen | Sporting Union Agen Lot et Garonne |

| Bayonne | Aviron Bayonnais |

| Biarritz | Biarritz Olympique |

| Bourgoin-Jallieu | Club Sportif Bourgoin-Jallieu |

| Brive-la-Gaillarde | Club Athltique Brive Corrze Limousin |

| Clermont-Ferrand | Association Sportive Montferrandaise ClermontAuvergne (Montferrand) |

| Castres | Castres Olympique |

| Montpellier | Montpellier Hrault Rugby Club |

| Narbonne | Racing Club Narbonne Mditerrane |

| Paris | Stade Franais |

| Pau | Section Paloise |

| Perpignan | Union Sportive Arlequins Perpignan |

| Toulon | Rugby Club Toulonnais |

| Toulouse | Stade Toulousain |

Introduction

Mercenary is not a pretty word. It sounds like a cold-eyedthug ready to change his loyalty for money. Iam a mercenary, and so are most of my friends. If,as George Orwell said, serious sport is war minus the shooting,we are its soldiers, playing out make-believe conflicts infront of partisan crowds. We do this for money and for thelove of the game, but mainly for the money.

As a rule we are known as professional rugby players. Thisis a bit like calling a spade a shovel: you could be forgiven forthinking they are the same thing, but if you have to actuallywork with one you soon see the difference. To understandwhat makes them different (professionals and mercenaries,not shovels and spades), you need to know about rugby.

These days rugby may look like an organised career move,but I fell into it for want of anything else to do. My degree inEnglish literature hadn't proved to be the instant passport toa high-flying career in journalism I had hoped. I had donesome work for a regional television station, but the stationhad quickly gone bust. After finishing a temporary job as assistantproducer for Radio New Zealand's Morning Report, Iwas looking for something to turn my hand to.

Foreign shores looked attractive. Friends from universitywere fetched up in far-flung, exotic places such as Paris,Moscow and New York. I applied to the Australian HighCommission for a job organising a forum in Nauru, a remoteisland with a population of 11,000 people and a landscapescarred by a century of phosphate mining. The job hadn'tpreviously featured on my ideal career path, but I was guttedto miss out. Various other possibilities turned out to be deadends.I was stuck in the young person's Catch-22 whereall jobs require experience and there is no way to acquireexperience because you can't get a job.

And then rugby went professional. It felt like winningLotto without even buying a ticket. At 24, I al ready had fifteenyears' experience of the game, and given the limited timespan of a rugby career I could even be said to be approachingmy peak. Rather than struggling to get on to the bottom ofthe ladder in some other rat race, I could slot in somewhere inthe middle of the newly created, and apparently relatively lucrative,rugby market.

Of course, no one starts out playing rugby because of money.Like any sport, you get into it because it looks like fun, oryou are press-ganged by an overbearing father. As is often thecase in New Zealand, I started playing at school. Whereveryou start, part of rugby's attraction is the reassuring sense ofbelonging to something bigger than you. You make friendswith team-mates, and have a role to play in a group thatneeds you to perform well. Representing your school or yourclub or your town against all comers, you share the joy ofvictory and the bitter taste of defeat, discover the benefits ofhard work, learn how to complain about the referee and theunfairness of it all, and generally grow up.

So far, this is much like any other team sport. The magicof rugby, though, lies in its peculiar emphasis on two basicpillarsinclusiveness and interdependence. Compared to arelatively simple game such as soccer, rugby's rules arecomplex enough to need a variety of different body types andskills. In a rugby team there is a place for everyone: fat kids(or 'big-boned children', if their parents prefer) prop thescrum; the tall and ungainly like me are predestined to playlock; rangy, athletic types become loose forwards; the moredexterous, intelligent players run the game from the halfbackpositions; nimble runners find themselves in the outsidebacks. If you are scrawny, slow, dull-witted and uncoordinated,you may find your participation limited to bringing onthe oranges at half-time; the writing is on the wall. You couldalways become a referee.

Put simply, the aim of a rugby team is to get hold of theball, and to organise so that one player places the ball behindthe goal-line to score a try. Equally important, of course, ispreventing the opposition doing the same thing. All this requiresteamwork, certain special skills and physical courage.I am not going to get involved in rules or tactics because thatwould take up a book in itself. Yes, you can kick the ballbetween the posts as well, but that isn't really the heart of thegame. History buffs will tell you the reason a try is called a'try' is that when the game was first played it was worthnothing: putting the ball behind the line merely gave you thechance to try for a shot at goal. But the game has moved onsince then.

The nature of rugby as a contact sport'collision sport'is perhaps more appropriatemeans physical courage isimportant. In terms of injuries, rugby is right up there at thetop of the table. Throwing yourself at someone running atfull speed is, under normal circumstances, verging on theinsane, and not something that comes naturally. For youngmen this is, of course, part of the attraction: the danger raisesthe stakes, and by facing up to it you get to prove to yourpeers that you are reliable and brave. Your mates have toprove themselves as welleach player must provide his ownparticular skills if the team is to be successful, and strongbonds of mutual respect soon form. The performance of theteam becomes a source of pride, reinforcing the sense ofbelonging to the community. Rugby playersincludingwomenare often seen as macho, and there is a pleasinglyprimal element to the game that appeals to unsophisticatedbut deeply rooted parts of our nature.