Copyright 1994 by Yale University

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Designed by Gillian Malpass

Set in Linotron Bembo by Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Daniell, David.

William Tyndale: a biography / by David Daniell.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-06132-1 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-300-06880-1 (pbk)

1. Tyndale, William, d. 1536. 2. Reforamtion-England-Biography.

I. Title.

BR350. T8D33 1994

270.6&'092-dc20

[B] 94-17509

CIP

A catalogue record for this book is available from

The British Library

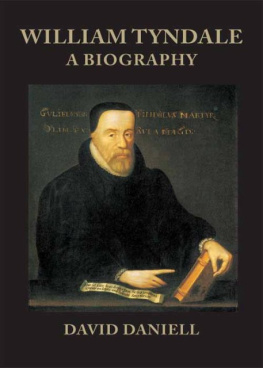

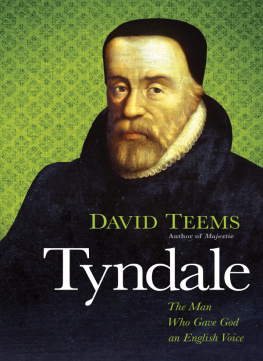

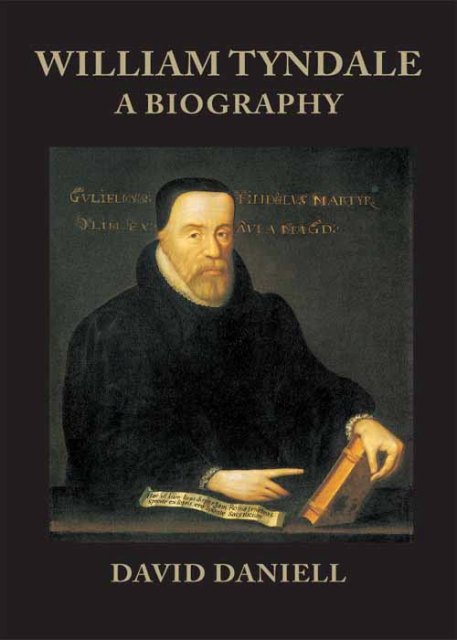

Frontispiece: Anon., William Tyndale,

mid-sixteenth century (?).

Reproduced by kind permission of

the Principal of Hertford College, Oxford.

4 6 8 9 7 5

To Andy

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people have contributed to the making of this book. I want first of all to thank Tyndale enthusiasts across the world, a band that seems to increase daily, whose inspiring letters and phone calls have meant a great deal in the two years of its writing. I have felt compassed with so great a multitude of witnesses as Tyndale puts it in Hebrews 12, and I am sorry that it is not possible to mention all by name.

I am especially grateful for specialist help in London. In the Library of University College London, John Spiers has been unfailingly resourceful and prompt with advice, with suggestions and even with books in hand, showing a patience with me that cannot have been easy amid the minute-by-minute demands from queues of students. Dr Michael Weitzman of the Department of Hebrew Studies at University College has illuminated my understanding of the Hebrew Bible with great wisdom and, again, patience, in many sessions. In the later stages Vanessa Champion-Smith did excellent research.

Professor Gerald Hammond of the University of Manchester gave much-needed encouragement and advice throughout the writing, and made his expertise freely available. Dr Anthea Hume of the University of Reading gave me permission to use her unpublished 1961 doctoral thesis, A Study of the Writings of the English Protestant Exiles, 152535: as will be apparent, her pioneering work has influenced my thinking at many points and I am glad to express in this book my particular appreciation. Miss Joan Johnson, the Gloucestershire historian, and Dr Joseph Bettey of the University of Bristol answered my questions by return of post.

For help with pictures I am glad to thank Vanessa Champion-Smith again and Tim Davies, Robert Ireland, Gertrude Starink, Andrew Valentine and the Revd. Dr Morris West.

I owe a special debt of thanks to Sue Thurgood, who worked under the greatest pressure to get the final text in order and presentable, twice. Without the initiative, skills and patience of Gillian Malpass at Yale University Press this book would not have happened.

The specialist knowledge of my elder son, Chris, saved me from many historical follies and his interest throughout has been an inspiration. I have also been rescued by his computer skills. The book is dedicated to my younger son, Andy, who set out on a different, but parallel, intellectual voyage. My deepest debt is to my wife, Dorothy, who has lived with Tyndale as well as me for two years: without her nothing at all would be possible.

Leverstock Green

May 1994

INTRODUCTION

William Tyndale gave us our English Bible. The sages assembled by King James to prepare the Authorised Version of 1611, so often praised for unlikely corporate inspiration, took over Tyndale's work. Nine-tenths of the Authorised Version's New Testament is Tyndale's. The same is true of the first half of the Old Testament, which is as far as he was able to get before he was executed outside Brussels in 1536.

Very many of the treasures which have enriched the lives and language of English speakers since the 1530s were made by Tyndale: a long list of common phrases like the salt of the earth or let there be light or the spirit is willing; the haunting phrasing in parables like the Prodigal Son, this thy brother was dead, and is alive again: and was lost, and is found; the gospel stories of Christmas (there were shepherds abiding in the field) through to the events of the Passion in Jerusalem and the Resurrection: in the Old Testament, the telling of Creation and of Adam and Eve, right through the history told there to the Exile in Babylon. All these things came as something new to the men and women of Tyndale's time in the 1520s and 1530s. That was because Tyndale translated them, for the first time, from their original texts in Greek and Hebrew, into English; and then printed them in pocket volumes for everyone to own. Apart from manuscript translations into English from the Latin, made at the time of Chaucer, and linked with the Lollards, the Bible had been only in that Latin translation made a thousand years before, and few could understand it. Tyndale, before he left England for his life's work, said to a learned man, If God spare my life, ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou dost. He succeeded.

The outlines of Tyndale's life have been generally known: the years at Oxford and in Gloucestershire, the fruitless attempt to get the Bishop of London to support him, the exile to Germany and the Netherlands; the cargoes of Testaments smuggled into England; his arrest in Antwerp, imprisonment and, charged with heresy, burning. There has not been a full-scale study of him for nearly sixty years, since J.F. Mozley's biography of 1937, itself based on that by Robert Demaus in 1871 (Brian Edwards's excellent God's Outlaw of 1976 is a semi-fictionalised account). There is need for something more modern, especially as the quincentenary of Tyndale's birth in 1494 is widely celebrated.

There have always been those who unfashionably recognised something of his worth: but at the end of the twentieth century his achievement begins to look substantially greater than has ever been understood. William Tyndale was a most remarkable scholar and linguist, whose eight languages included skill in Greek and Hebrew far above the ordinary for an Englishman of the timeindeed, Hebrew was virtually unknown in England. His unsurpassed ability was to work as a translator with the sounds and rhythms as well as the senses of English, to create unforgettable words, phrases, paragraphs and chapters, and to do so in a way that, again unusually for the time, is still, even today, direct and living: newspaper headlines still quote Tyndale, though unknowingly, and he has reached more people than even Shakespeare. At the centre of it all for him was his root in the deepest heart of New Testament theology, a faith of the sort that can, and did, move mountains. Tyndale as theologian, making a Reformation theology that was just becoming discernibly English when he was killed, has been at best neglected and at worst twisted out of shape. Tyndale as conscious craftsman has been not just neglected, but denied: yet the evidence of the book that follows makes it beyond challenge that he used, as a master, the skill in the selection and arrangement of words which he partly learned at school and university, and partly developed from pioneering work by Erasmus. These things are shown in his treatises, but, together with his understanding of languages, they make the core of his Bible work. For him, an English translation of the Bible had to be as accurate to the original languages, Greek and Hebrew, as scholarship could make it; and it had to make sense. There are times when the original Greek, and for good reason even more the Hebrew, are baffling. A weak translator goes for paraphrase, or worse, for philological purity, and hang the sense (as the Authorised Version did often with the Prophets, for example, in those books lacking Tyndale as a base). Tyndale is clear. With a difficult word or phrase, he understands the alternatives presented by technical semantics, or changes of tone or feeling, and goes for what makes sense. In the pages that follow we shall watch that process again and again.

Next page