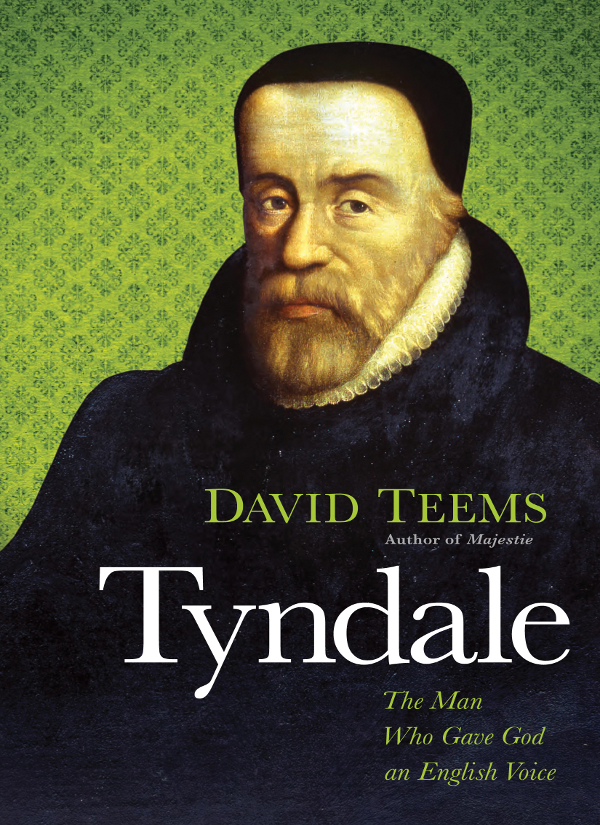

Praise for Tyndale: The Man Who Gave God an English Voice

Teems concentrates not on what was important to Tyndales peers and contemporaries, nor yet to his more modern biographers, but on what was important to William Tyndale himself... It is an unfashionable thing today to speak of spiritual matters in any biography, but Teems, rightly, is not afraid to do so.... He writes pithily and concisely: this is no stodgy pudding served up on a pedants plate, so dont expect to be left with the usual bout of mental indigestion halfway through.... Teems biography will refresh many peoples thinking concerning the unique and remarkable man, William Tyndale.

Dr. William Cooper,

The Tyndale Society Journal

From the time we first met David Teems, I have loved this mans heart, mind, and writing. I have followed the trail, both of his words to music and also his poetry and prosethe depth of his soul, the sharpness of his insights, and the breadth of his subject matter. These, added to the tender compassion and sensitivity of his art, have culminated in the carefully researched and beautifully written Tyndale: The Man Who Gave God an English Voice.... Teems paints not only a scholar focused on translating the scripture in its original intention, but a poet who did so with such simplicity and beauty that we still quote and set to memory the perfectly-turned phrases and sentences given to us in the 16th century by William Tyndale.

Gloria Gaither

I have been personally inspired and challenged by the life of this great man William Tyndale, and am in great debt as well to David Teems for brilliantly bringing this remarkable story to life.

Ricky Lee Jackson, MD

Teems provides an amazing account of an amazing man, of whom not much is written or known. But through the writings we can see into the heart of William Tyndale and the gentleness with which he approached his task and his detractors. I cannot recommend this book enough to students of history, of the Bible, or [people] compelled to write or translate a great work.

M. Bailey

2012 by David Teems

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, scanning, or otherexcept for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published in Nashville, Tennessee, by Thomas Nelson. Thomas Nelson is a trademark of Thomas Nelson, Inc.

Published in association with Rosenbaum & Associates Literary Agency, Brentwood, Tennessee.

Thomas Nelson, Inc., titles may be purchased in bulk for educational, business, fundraising, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail SpecialMarkets@ThomasNelson.com.

Certain Scripture quotations are from the NEW AMERICAN STANDARD BIBLE, The Lockman Foundation 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995. Used by permission.

Certain Scripture quotations are from The Message by Eugene H. Peterson. 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2000. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group. All rights reserved.

Certain Scripture quotations are from the KING JAMES VERSION.

Certain Scripture quotations are from the Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV. 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved worldwide. www.zondervan.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Teems, David.

Tyndale : the man who gave God an English voice / David Teems.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-59555-221-1

1. Tyndale, William, d. 1536. 2. Bible. EnglishVersionsTyndale. I. Title.

BR350.T8T44 2012

270.6092dc23

[B]

2011028649

Printed in the United States of America

To Ward Allen

For his infectious sparkle. For his gentle nod of assent.

Where the Spirit is, it is always summer.

William Tyndale

Contents

I come no more to make you laugh: things now,

That bear a weighty and a serious brow,

Sad, high, and working, full of state and woe...

Those that can pity, here

May, if they think it well, let fall a tear;

The subject will deserve it.

William Shakespeare, The Life of King Henry VIII

THE OLD WORLD WAS DYING, AND WITH AN INCH OF POISON AROUND its heart. The Middle Ages was coming to its slow climactic end, and in a blaze of flesh and madness. It would not give up without a fight. Otherwise good men were swept up in a kind of collective psychosis. The times were treacherous. And H8 was king.

Church and state tolerated a kind of shared headshipoften a troubled or aggravated headship, but a league nonetheless. Rulers were validated with a nod from Rome, and the papal court was not unlike that of royalty. The

Christianity was indeed the matrix of medieval life. You could do very little without the blessing of the Church. The Catholic Church governed birth, marriage, death, sex, and eating, made the rules for law and medicine, gave philosophy and scholarship their subject matter. It taught the faithful how to spend their money, how to sweat their tithe, what to believe, what to think.

Culture grew within and around the Church. She was the watchful parent. And membership was not optional, it was not a matter of choice; it was compulsory and without alternative, which gave it a hold not easy to dislodge.

The Renaissance, however, with its discovery of the New World, with its reinterpretation of the cosmos and mans reassigned place within it, with the downsizing of the great myths that had driven culture along, allowed man to reimagine himself. And becoming self-aware, he didnt necessarily need nor want a demanding mother. Such an evolutionary state in the progress of man could not help but create a powerful tension. It is within this tension that our story lives.

Myopia

The aggravation was an old one that went as far back as John Wycliffe (13281384), who argued that temporal matters belonged to the civil powers alone, that the monarchy was superior to the priesthood. And while his angels-dancing-on-the-head-of-a-pin contemporaries were asking questions like Does the glorified body of Christ stand or sit in heaven? or Is the body of Christ, eaten in the sacrament, dressed or undressed? Wycliffe started asking better questions. His questions, as well as the answers he gave them, were incendiary.

Revenues were flooding into the Church from all compass points and from a variety of cleverly invented streams. Wycliffe, however, could find no justification in Scripture for the organization of the church as a feudal hierarchy, or for the rich endowments the Church enjoyed.

The Church was incensed at Wycliffe for his ideas, for his audacity, for his objection to the doctrine of transubstantiation among other things, and for his insistence on a vernacular Bible, which he and his associates produced in 1382. Had he not died of a stroke two years later, he would have burned for his trouble.

But John Wycliffe died of natural causes. William Tyndale did not. There is hardly anything natural about condemning a man to burn alive and finding contentment in the act, a pious contentment at that, as if Christ had been done some honorable service.

At the heart of medieval Christianity, if indeed it had a heart, was a reliance on fear and manipulation. The capacity to inspire terror in its faithful was the first rule of order and dominion. The only modern analogue might be radical Islam, with its commitment to

Next page