All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

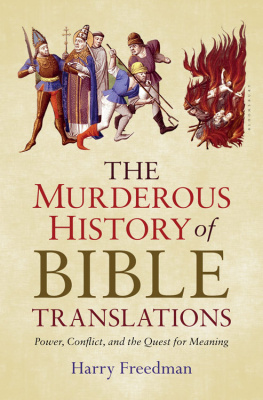

On the Burning of Heretics

E arly in the year of Our Lord 1428, the mortal remains of a former rector of the parish were exhumed from beneath the flagstones in the chancel of St Marys Church in Lutterworth, a market town in the English Midlands. An array of powerful men stood out from the plain crowd of local people in the church. Richard Fleming, the bishop of Lincoln, in whose see Lutterworth then lay, was present with his chancellor, his suffragan bishops and the priors and abbots of the diocese. The high sheriff of Leicestershire was attended by his officers. A coterie of canons and lawyers huddled round the gravediggers as they worked. An executioner looked on with professional interest.

The coffin was raised, and opened, and its contents were exposed to the onlookers. The body was then taken out through a small door in the south side of the chancel, as the dying rector had been carried by his parishioners forty-four years before, after he suffered a stroke while celebrating mass in December 1384. His remains were borne in solemn procession, under the dripping yews in the churchyard, along the streets of the town and down the wooded hillside to a field next to the hump back bridge that crossed the River Swift.

This was a field of execution. Public hangings continued here into coaching days, when Lutterworth was an important staging post on the route north from London past Leicester. The dead rector, however, was thought too evil to hang. A stake had been set up in the ground and piled with timber and kindling. Iron chains were attached to it at shoulder height. He was to be burnt.

A brief ceremony was held. Bishop Fleming confirmed that he was carrying out the command sent to him from Rome by Pope Martin V on 16 December last. This ordered him to carry out the sentence that had been passed on the body in 1415 by the great Council of the Church meeting at Constance on the GermanSwiss border. The council had condemned two hundred propositions put forward by the dead man, John Wycliffe, the former master of Balliol College at Oxford and rector of Lutterworth, that touched on core doctrines of the Catholic faith. The council found that since the birth of Christ no more dangerous heretic has arisen, save Wycliffe. It instructed that his body be removed from the consecrated ground in the chancel at Lutterworth and destroyed.

Tradition allowed for the body to be dressed in the vestments that the rector had worn to celebrate mass, so that these could be stripped from him, chasuble and stole, one by one, to signify that he was unfrocked and deposed from the priesthood. We do not know if this ritual was observed, or whether Wycliffes skull and fingers were scraped, to represent the removal of the oil with which he had been anointed at his ordination. Certainly, the bishops solemnly cursed him and commended his soul to the devil.

Heresy had been declared to be treason against God by Pope Innocent III in 1199, and was thus regarded as the worst of all crimes. Its vileness was said to render pure even Sodom and Gomorrah, while the great medieval theologian St Thomas Aquinas declared that it separated man from God more than any other sin. The Church imposed a double jeopardy on heretics. The earthly poena sensus, the punishment of the senses, was achieved by the stake and the fire. If, like Wycliffe, the person was convicted after he was dead, the penalty was imposed on his remains. The poena damni proclaimed by the bishops on Wycliffe pursued his soul into the life everlasting. It damned him to absolute separation from God and to an eternity in hell.

The Church could not itself carry out a burning. To do so would defy the principle that Ecclesia non novit sanguinem, the Church does not shed blood. Pope Lucius III had bypassed this inconvenience in 1184 by decreeing that unrepentant heretics should be handed over to the secular authorities for sentence and execution. After cursing the remains, Bishop Fleming therefore delivered them up to the high sheriff of the county, as the representative of the civil power. The sheriff declared that they should be burnt by the executioner.

The executioner attached the dead man to the stake with the iron chains before setting fire to the kindling. He made sure that the bones and skull were burnt to ash in the fire, breaking them into small pieces with a mattock to help the process, until they merged into an indistinguishable grey pile of ash and embers. These were carefully scraped into a barrow. When the last particles of dust were swept clean from the patch of scorched earth, the barrow was tipped into the waters of the Swift.

Only then was the bishop sure that he had fulfilled the papal instructions, to rid the world of all physical trace of the heretic. Any relic might otherwise be gathered up by the dead mans supporters and placed in a shrine to perpetuate his accursed memory.

Fleming did his work well enough; he earned his altar-tomb in Lincoln Cathedral, where his bones lie undisturbed, and his renown as the founder of Lincoln College at Oxford. Only a few physical scraps remain that connect directly with Wycliffe: a fragment of his cope, an ancient pulpit and a font that he may have used. waters of the Swift, his followers noted, flowed into the Avon, the Avon into the Severn, and the Severn into the sea, so that the whole world and all Christendom became his sepulchre.