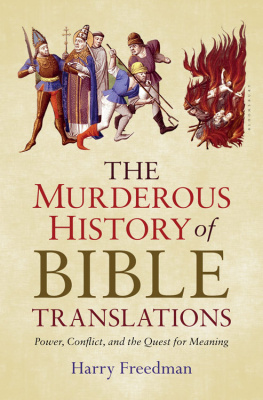

The Murderous

History of Bible

Translations

For Eli. Already gifted in several tongues.

The Talmud: A Biography

The Gospels Veiled Agenda

Pursuing the Quest: Selected Writings of Louis Jacobs

Jerusalem Imperilled

How To Get a Job In a Recession

The Murderous

History of Bible

Translations

Power, Conflict and the

Quest for Meaning

Harry Freedman

Most of us take the Bible for granted. That is to say, irrespective of our religious beliefs we assume that the Bible in our hands, or the one we never take off the shelf, or the copy in the hotel drawer, has always been the way we see it now. Like any other book, it was written, printed, bound, published and is sometimes read. It may or may not be, depending on our views, sacred or divine. But thats not the point. It is what it is; its the Bible.

The Bible that most of us are familiar with is not printed in its original languages. Its a translation. Translators tend to be anonymous people; when we read a foreign book in our own language we know who wrote it; we dont think much about who translated it. But the people who translated the Bible, many of them anyway, were not just ordinary translators commissioned to render a piece of literature into a different language. Almost without exception, they had a story. And for many of them, their story is every bit as illuminating, and frequently as violent, as the Bible itself.

In 1535, William Tyndale, the first man to produce an English version of the Bible in print, was captured and imprisoned in Belgium. A year later he was strangled and then burned at the stake. A co-translator, John Rogers, was also burned. In the same year, the translator of the first Dutch Bible, Jacob van Liesveldt, was arrested and beheaded. They werent the only Bible translators to meet a grizzly end, they just happen to be among the best known.

The history of Bible translation has not always been murderous, but it has rarely been lacking in contention. Even in our own time the controversies have rarely gone away. The politics of modern Bible translation is peppered with arguments and disputes about how to read the Good Book, and what it really says. The violence has dissipated but, given the history of religious conflict, it is not unthinkable that it may one day return. Religion generates extreme emotions. Unlikely as it may seem, there is only a fine line between Bible translation and sectarian conflict.

The translated Bible lends itself well to polemic and religious manipulation. The sixteenth-century translators of the Geneva Bible harnessed it to promote their anti-monarchist views. The medieval Church used it as a whipping boy, prohibiting its use to ensure that people believed what they were told, not what they read, or had others read to them. Missionaries and evangelists throughout history have relied upon it to promote their message among non-believers.

The Bible is central to western civilization and the Judeo-Christian tradition. One doesnt need to be a believer to recognize that many of the principles we hold dear come straight from its pages. Can we imagine a world in which it had not been translated? If the Bible had remained exclusively in the hands of the priests, would science, education and freedom have prospered? Alternatively, had the hallmarks of civilization developed wholly independently of religion, is it conceivable that someone would not have translated the Bible?

The translated Bible was intended to be radical, liberating and inspirational. Yet in the hands of religious conservatism it became a negative force, a barrier to social evolution. In its earliest narrative, the story of the translated Bible reflects the separation of early Christianity from its Jewish ancestry. Centuries later, it became a paradigm for the battle between medievalism and modernity. And in modern times the experiences of the translated Bible encapsulate all the uncertainties afflicting formal religion in an open and secular age. But at no time has the translated Bible been free from violence; even now, when there is little physical threat, the turbulence a new translation engenders is palpable. The translated Bibles history is truly murderous.

Nobody ever sat down with the intention of writing a Bible. How could they? The concept didnt exist. Over the course of many centuries, individuals under varying degrees of inspiration wrote accounts of revelations, histories, prophecies and myths. The Bible is a collection of some of these accounts, or more accurately, three collections. The earliest collection is known colloquially as the Old Testament, the Bible of the Jews. The most recent is the Christian New Testament. A third, slightly less revered compendium is known to the Catholics as the Deuterocanon and to everyone else as the Apocrypha.

The process of translating the Bible, of bringing it to the masses, began even before the collections, or canon, were complete. Parts of the Bible were being translated even as it was being written. The book of Nehemiah, one of the later volumes in the Old Testament, relates how Ezra the Scribe translated the Five Books of Moses for the benefit of Aramaic-speaking, Jewish refugees returning home from Babylon. Acts of the Apostles describes how the Bible was miraculously translated into many languages simultaneously. But the first Bible translation controversy did not erupt until much later, early in the second century of the Common Era. The cycle of controversies took several hundred years to reach a climax. Things moved more slowly in those days.

This book tells the story of those for whom the idea of a Bible that ordinary people could read was so important that they were willing to give up their time, their security, often even their lives. It tells the story of the translated Bible, but it does not pretend to be a comprehensive history of the translated Bible. Too many books on the Bible are overlong and full of dry facts; that is fine for an academic work but it can wear down readers who are not looking to become experts in the field. So, in this eclectic account, many translations, and many seminal characters in the translated Bibles history, get scarcely a mention, either because they managed to remain free from controversy, or because their story adds little to what has already been said. For similar reasons we do not delve into the technicalities of translation techniques, nor fret over contentious interpretations. The Bibliography lists many of the good books available on these and other subjects, for those who are interested.

Just a word on terminology. No designation of the Bible or its various constituents will satisfy everybody. For Jews the Bible is only the Old Testament, but the name itself is inappropriate because it implies that their Bible has been superseded. For Christians the Bible means both Old and New Testaments, together with the Deuterocanon, or Apocrypha, for Catholics and Orthodox, and without it for many Protestants. The order of the books in the so-called Old Testament is different for Jews, Protestants and Catholics. To keep things simple I have used the traditional terms of Old and New Testament throughout and tried not to dwell overmuch on the various definitions of what actually constitutes the Bible.

The Legend of the Septuagint

The story begins, as many good stories do, as a shard of truth, deeply buried within a legend. We are unlikely ever to uncover the whole story but the legend is as good a place to start as any.

Next page