It Starts with Trouble

William Goyen and the Life of Writing

CLARK DAVIS

University of Texas Press

AUSTIN

Copyright 2015 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

First edition, 2015

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

http://utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp-form

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Davis, Clark, author.

It starts with trouble : William Goyen and the life of writing / Clark Davis. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-292-76730-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Goyen, William. 2. Authors, AmericanBiography. I. Title.

PS3513.O97Z46 2015

813'.54dc23

[B]

2014031607

doi:10.7560/767300

ISBN 978-0-292-77194-9 (library e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-77195-6 (individual e-book)

In memory of Martin Pops

What starts you writing?

It starts with trouble. You dont think it starts with peace, do you?

GOYEN, TRIQUARTERLY INTERVIEW (1982)

Contents

List of Abbreviations

| AR | Goyen, William. Arcadio. New York: Clarkson Potter, 1983. |

| BOJ | Goyen, William. A Book of Jesus. New York: Doubleday, 1974. |

| CR | Goyen, William. Come, the Restorer. Evanston: TriQuarterly Books and Northwestern University Press, 1996. Originally published 1974. |

| CS | Goyen, William. The Collected Stories of William Goyen. New York: Doubleday, 1975. |

| FS | Goyen, William. The Fair Sister. New York: Doubleday, 1963. |

| GAE | Goyen, William. Goyen: Autobiographical Essays, Notebooks, Evocations, Interviews. Ed. Reginald Gibbons. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007. |

| HHM | Goyen, William. Had I a Hundred Mouths: New and Selected Stories, 19471983. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1985. |

| HLC | Goyen, William. Half a Look of Cain: A Fantastical Narrative. Evanston: TriQuarterly Books and Northwestern University Press, 1994. |

| HOB | Goyen, William. The House of Breath. Evanston: TriQuarterly Books and Northwestern University Press, 1999. Originally published in 1950. |

| HRC | William Goyen Papers, ca. 19231984. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, the University of Texas at Austin. Box and folder numbers are cited where available. |

| IFC | Goyen, William. In a Farther Country: A Romance. Evanston: Tri-Quarterly Books and Northwestern University Press, 1995. Originally published in 1955. |

| SL | Goyen, William. Selected Letters from a Writers Life. Ed. Robert Phillips. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995. |

| WP | Goyen, William. Wonderful Plant. Palaemon Press, 1980. |

| WRC | William Goyen Papers, 19371978. Woodsen Research Center, Fondren Library, Rice University. Box and folder numbers are cited where available. Goyens family correspondence is in WRC 3.7 through 4.13; his correspondence with William Hart is in WRC boxes 13. Quoted material courtesy the Woodson Research Center. |

Introduction

I remember Marian Anderson was my first experience with what truly was a spiritual moment. Suddenly when she sang she was purely an instrument for the spirit, pure spirit. Through her mouth, here was this blessed moment, the light and the fire were on her, way beyond her training or the song itself. I was sixteen; I identified thoroughly, purely, with her. Thats where I belong, I come from that, I said. Thats why I feel so alone, because I belong to whatever that was.

WILLIAM GOYEN, TRIQUARTERLY INTERVIEW, 1982

Unlike Truman Capote, William Goyen matured without betraying his sensitivity, he became stronger without surrendering the qualities which made him both human and subtle, able to handle overtones in relationships without destroying them in the process. The balanced, harmonious maturity of sensitiveness is a rare quality in our culture, for it usually does not have the endurance to survive.

ANAS NIN, THE NOVEL OF THE FUTURE

William Goyen is a unique and lonely figure in American literature. Though praised and recognized as a remarkable talent, particularly early in his career, he never felt welcome in the literary world. When asked in 1975 if he saw himself as part of the writing generation that included William Styron, Truman Capote, and Norman Mailer, he admitted that he felt immensely apart.... I still feel apart and, well, I am apart from my contemporaries. And they dont know what to do about me, or they ignore me. I am led to believe they ignore me (GAE 96). This isolation was partly the result of a fundamental feeling of estrangementfrom home, family, from most forms of community. In part it was a function of his commitment to an idea: that the artist is his only subject and art a sacred act of finding a form for the souls disorder. For Goyen, writing was never simply a matter of self-expression, nor was it a kind of economic manufacture; it was a struggle to stay alive, to wrest a blessing from the angel. Ive limped out of every piece of work Ive done, he revealed in a lecture just before his death. Its given me a good sock in the hipbone in the wrestling. My eyes often open when I see a limping person going down the street. That persons wrestled with God, I think.... Work, for mewriting, that ishas been that renewal through wrestling, that naming, that going home, that reconciliation with old disharmony, grief, grudge (GAE 66).

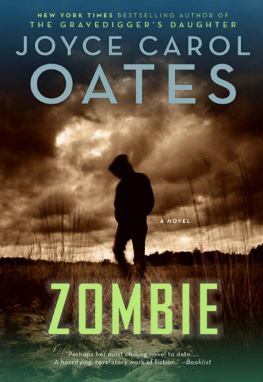

In her 1983 introduction to Goyens final collection of short stories, Joyce Carol Oates attempted to capture the wounded Texans unique place in his countrys literature, calling Goyen the most mysterious of writers. He is poet, singer, musician as well as storyteller; he is a seer; a troubled visionary; a spiritual presence in a national literature largely deprived of the spiritual (HHM vii). The description is apt and perceptive. Yes, Goyen remains a mysterious, almost elusive figure; his obsessive, worried stories do indeed live in the spaces between music and narrative; and his language, though dramatic and insistent in its way, pushes at clarity, hoping to see through the skin of the real. And yes, theres troublelots of it: deep disturbance and unspecified desire that push his lonely characters to tell their haunted stories.

But how exactly is Goyen a spiritual presence? And how can American literature be thought of as spiritually deprived?

It might have been more obvious to suggest that spiritual concerns have dominated American literature, particularly in its early phases. Literary historians often speak of the biblically soaked language and mindset of American writing at least until the Civil War, and its difficult to see the Transcendentalists, for example, as nonspiritual, whatever their other attributes. But to recognize a religiously derived culture or an Old Testament style is not to identify the spiritual itself as a mode or content of the writing. And one of Goyens primary goals for his fiction was precisely thisthe embodiment of spirit in language, the evocation through colloquial music of a real, human presence. In an interview conducted near the end of his life, he tried to explain how a story, through the discipline of style, can create a heightened form of personal encounter:

Next page