CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

One day in the summer of 2010, as I was chatting with the Yellowstone National Park archivist and historian Lee Whittlesey about the challenges of writing a revisionist history, he handed me a quotation from the distinguished Western historian Elliott West, which he kept pinned to the wall of his office: The use of revisionist has always struck me as odd. We historians are all in the revision business, arent we? If we dont ask new questions and work toward some fresh understanding, whats the point? Treating past historians respectfully is our obligation; revising and building on what they have done is our job.

This, then, is a revisionist history, and it seeks to ask new questions about the nineteenth-century West. My intention has not been to pull back the curtain on the dark side of Yellowstone, although some readers may well see it that way. Rather, it is an account, starting with Lewis and Clark and ending with the last spasms of the Indian wars, of how the intertwined paths of settlement, exploration, violence, and institution-building all converged toward the discovery in 1870 of the most remote, inaccessible, and mythic corner of the Western frontier.

It is a story of men at a particular moment in history, of individuals who acted not only according to the dictates of their own character but within the values, culture, and institutions of their time, with all their attendant passions, ambitions, ideals, fears, and uncertainties. Strange contradictions arise in people during times like these, when societies are in the process of being redefined. Principled citizens justify acts of extreme violence, and ruthless military men develop a passion for education and knowledge. Retiring city-dwellers become intrepid explorers, and venal businessmen display unexpected bursts of altruism.

Historians often warn against presentismthe danger of relying on contemporary values to pass moral judgment on people of a different time. A certain amount of presentism is probably inescapable, but I have done my best to place my characters in the fullness of their historical contextthe decade following the Civil Warwith all its contradictions. At the heart of my story is a great paradox: that no matter how deeply flawed these characters may be as individuals, no matter how mixed their motives, and no matter how much damage they caused along the way, the paths they opened led to one of the true glories of American historythe creation of the worlds first national park. In that sense, the epic of Yellowstone is a quintessentially American story, of terrible things done in the name of high ideals, and of high ideals realized by dubious means.

At first it felt presumptuous for a foreign-born New Yorker to write about a period and a place that has already filled so many bookshelves. But the more time I spent in and around Yellowstone, the more I was struck by the fact that while some of the friends I made there were natives of Montana or Wyoming, the majority were not. They came from Pennsylvania and upstate New York, from Michigan and Arkansas, from Virginia and New Jersey, from Oklahoma and Ohio. All of us are drawn to this place, I think, by the same magnetic force that worked on the nineteenth-century settlers and explorersthe sheer wonder of the landscape of mountains, rivers, and skies, the sense that something primordial is still present and available to us.

I am deeply indebted to these friends for whatever virtues this book may possess. In particular I thank Paul Schullery, Kim Allen Scott, and Lee Whittlesey, who know these places more intimately than I ever will and read drafts of this manuscript with care and insight. Many others have offered generous support and companionship along the way, or enriched my travels with their insights into particular corners of the Yellowstone landscape. They include Linda Baker, Doug Barasch, Frances Beinecke, Glenn Brackett, Peter Carey, Emily Cousins, Louise Desalvo, Gerald Doane, Jason Doane, Dr. Wilton Doane, Bob Doerk, Maya Dollarhide, John Echohawk, Mike Foster, Janet Gold, Bruce Gordon, Andrew Graybill, Laurie Gunst, Phil Gutis, Karl Hepner, Darrell Kipp, Jack Lepley, Jesse Logan, Amy McCarthy, Forrest McCarthy, Wally MacFarlane, Bill McKibben, Dick Manning, Marlene Deahl Merrill, Peter Messina, Cullen Murphy, Jane Pargiter, Karen Perszyk, Philip Perszyk, Ken Robison, Paulette Running Wolf, Tracy Stone-Manning, Meredith Taylor, Laura Wright Treadway, Tom Turiano, L. J. Turner, Louisa Willcox, and Lesley Wischmann.

Librarians and archivists are one of our societys unsung treasures, and I am grateful to Jodie Foley, Lory Morrow, Zoe Ann Stolz, and their colleagues at the Montana Historical Society in Helena; Patricia Engbretson at Montana State University in Bozeman; Colleen Curry, Anne Foster, Bridgette Guild, and Jackie Jerla of the Yellowstone National Park Heritage Research Center; Alison Purgiel at the Minnesota Historical Society; and the staffs of the American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming, Laramie; the Museum of the Mountain Man in Pinedale, Wyoming; the Butler Library at Columbia University, New York; the Beinecke Library at Yale University; and the incomparable room 315 at the New York Public Library.

These are tough times in the world of publishing, and I am endlessly appreciative of the wisdom and friendship of my agent, Henry Dunow, who has now held my hand through three very different books. For his sharp critical eye and warm support of this project, I am grateful to my editor at St. Martins Press, Michael Flamini. Vicki Lame, Eric Meyer, and John Morrone shepherded the manuscript effortlessly through the production process. Rob Grom, Michelle McMillian, and Baker Vail have made the book beautiful as well as, I hope, readable.

My special good fortune is to share my life with Anne Nelson, whose loving support and acute insights as a writer and editor have helped this book along in innumerable ways. She, David, and Julia remain the rock on which everything else is founded.

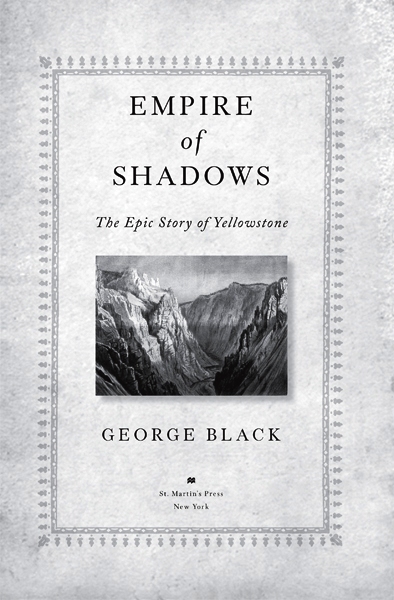

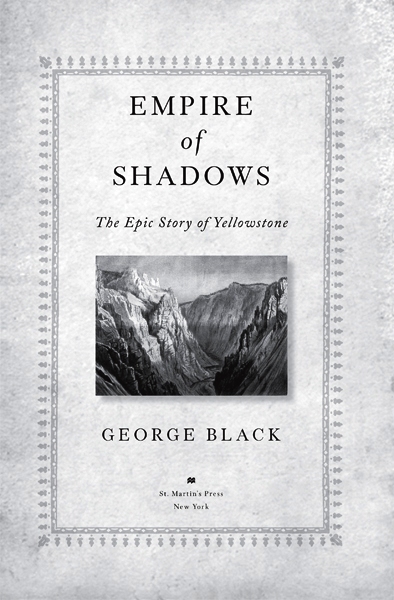

It is grand, gloomy, and terrible; a solitude peopled with fantastic ideas, an empire of shadows and of turmoil.

L IEUTENANT G USTAVUS C HEYNEY D OANE, S ECOND U . S . C AVALRY, ON THE B LACK C ANYON OF THE Y ELLOWSTONE, A UGUST 26, 1870

Prologue

THE VIEW FROM MOUNT WASHBURN

Nathaniel Pitt Langford left Helena a day ahead of the rest of the party. There were two important if unpleasant pieces of business to take care of before his unlikely group of explorers set off for the upper Yellowstone. He had chafed for five years to reveal the truth about this most inaccessible corner of the frontier, to settle once and for all the swirl of rumors about its hallucinatory wonders. Another day would not matter.

Langford was an expert horseman who had ridden alone for thousands of miles across the forbidding landscapes of Montana Territory with a shotgun strapped to his saddle, and he made a formidable impression. He was a handsome man of thirty-eight, with a black beard so dense that birds might have nested in it, a high forehead, a downturned mouth, and an intense, blazing stare. Most of the extant photographs capture his fierce charisma, though they also suggest an absence of humor, the self-righteousness of a man with strong and fixed ideas, and a taste for melodrama.

It was mid-August of 1870, but in one of those capricious turns in the weather that are so common in the Northern Rockies, Langford was caught in a snowstorm near the Three Forks of the Missouri. He bedded down there in the home of a retired army major, one of a straggle of cabins that some wishful thinker had called Gallatin City.