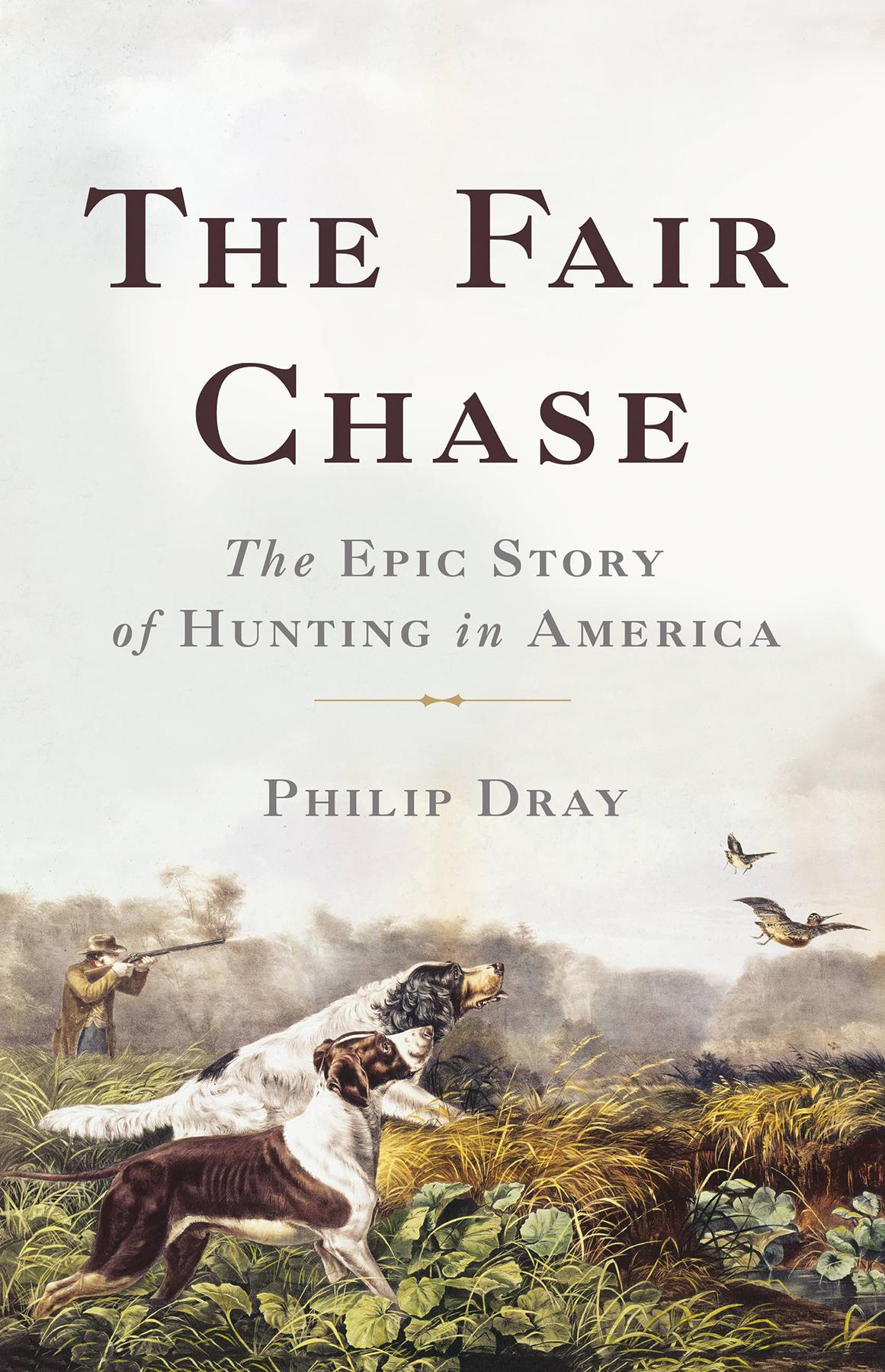

Less than 10 percent of the population now hunts, but they still represent a large symbolic place in our national narrative. Philip Dray helps us understand why hunting and hunters continue to shape our ongoing debates about our relationship to wildlife, endangered species, and environmental policy. Given the dramatic changes in the management ethos of our natural resources brought on by the Trump administration, The Fair Chase is a timely and engaging reminder of whats at stake.

J AN E. D IZARD , author of Going Wild and Mortal Stakes

They say bear is tastiest in late fall because the animals have been feeding for weeks on acorns, but it was pelts my friends wanted. It was early morning when luck blessed us: a she-bear and her cubs at the edge of a swamp. We cut the canoe in sharply toward shore and muffled our paddles, and not until we beached did the three of them run, the two cubs scrambling to the top of a tree, where they commenced to whine like puppies. Mama bruin doubled back the moment she missed her offspring, and faced us, partly rising on her hind legs. Swanson brought his rifle at his shoulder, and at the flash she fell where shed stood. We went over and were looking at her black coat, when suddenly instead of a dead bear we had a very live one, and the way George and I got out of reach was very rapid but inelegant. Swannie fidgeted too long with his gun, or so it seemed; finally he fired, and she was ours for good.

The boys began taking the skin, and then George decided he also wanted a cub, both of whom were still cowering in the treetop. A shot to the head brought one tumbling down. Seeing this gave Rusty bear fever, and he declared he wanted the other cub alive. With some difficulty they shook him out of the tree.

Once the mother bear was skinned we took the live cub with us, but the little bear would not sit still in the boat, so we let him go. He seemed tame enough then, and I stroked him on the back before he disappeared in the bushes. We floated down to Rainbow Lake, landed and George soon had a splendid trout dinner cooked

That night when the fire was fading Old Sturgis stopped by. He must have been about eighty, smoked a long Churchwarden pipe, and owned property thereabouts: a local character. When we mentioned our encounter with the bear and the cubs he puffed thoughtfully for a moment, and said, It reminds me of an incident up here long ago.

The four of us exchanged glances. We were already in our sleeping bags and bone-tired; no one was in the mood for one of his stories; but then he said, Had to do with a panther.

A panther? we exclaimed.

Solitary creatures, he nodded, loading the pipe, but abundantly sly. I doubt he even noticed our sudden interest, or maybe he took it for granted, for he was already lost in reminiscence. It was late in the fall, about this time of year, 1957. My brother Dick and I had come up with a new rifle he wanted to try. On our third day out we were just south of the falls when Dickie glassed a monstrous buck on the far side of the lake. When we crossed over we tracked him 1,000 yards up an old dry-wash and then not only lost him but ourselves, too. That evening Dick had to go back to town but I stayed on, determined to meet that deer again.

Night fell and I made camp next to a stream, just a mile or so from where we sit now. I built a fire and slept like the dead, but sometime during the night, long after my fire had gone cold, I awoke to one of the strangest sensations.

What was it? I asked.

Leaves; branches of dry leaves were being heaped upon me. I opened one eye long enough to see the panther slink off. She was trying to hide what she took for choice carrion: me!

Well, I resolved not to become anyones supper and to oppose cunning with cunning. I found a thick bough of a fallen tree and dragged it to the fire, put some leaves atop it, then went and hid behind a rock. She appeared before long, followed by two hungry cubs. Slowly she crept to within fifteen paces of the spot where she had left me covered up with leaves, and crouched down with her green eyes glaring at the log; the next instant she made a spring, struck the claws of both her fore feet into it, and buried her sharp fangs deep in the rotten wood.

Boys, the look on her face when she found herself deceived! She stayed for a moment in the same attitude, quite confounded. But I did not leave her time to deliberate; I put a bullet right into her brain, and down she dropped.

Jesus! What if youd missed?

Oh, I hate to think.

And what happened to the cubs?

I never knew, he said. Theyre likely all grown up and lurking around here even now, he said for effect, at which we all laughed, as we inched our beds a little closer together.

When hed left I asked Swanson if what the old codger had told us could possibly be true. No, he yawned. Go to sleep

Next morning we were all up just before sunrise, dressed, and after some barely warmed-up coffee walked out to the big meadow where deer were said to browse. We separated. I chose a large black walnut tree to settle under, the field slanting downhill before me and a small creek murmuring behind. Perhaps I dozed. Then as the sky lightened there came the sound of animals waking: yard dogs barking; the tinkle of a goats bell; some lambs mewing from over the ridge; out of the woods came a snorting sound, likely an elk or a deer. But I saw no deer, only listened to a woodpecker hammering away down in the valley.

As a boy I devoured stories like these, occasionally beneath the covers by flashlight, enthralled by the hunters stealthy advance into the nonhuman world, the sudden stir of leaves, and the well-made shot. All of Minnesota then seemed connected to the sport: antlered deer and moose stared down from the wood-paneled walls of local restaurants; one could buy a box of shotgun shells at many filling stations, and everywhere, even at the end of city blocks, paths led away to woods or wetlands. From an early age I heard the implied summons to wilderness in the states enchanted nickname, the Land of Sky Blue Waters. And it was with a sense of determination akin to pilgrimage that our first family vacation included a stop at the Hotel Duluth, where in 1929 a hungry black bear had smashed violently through a plate glass window and entered the coffee shop, the premises of which now displayed the intruder as a stuffed tourist attraction.