Published in 2020 by New York Times Educational Publishing

in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2020 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2020 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Caroline Que: Editorial Director, Book Development

Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Michael Hessel-Mial: Editor

Greg Tucker: Creative Director

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Hunting and gun ownership / edited by the New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York: The New York Times Educational Publishing, 2020. | Series: In the headlines | Includes glossary and index. Identifiers: ISBN 9781642823066 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642823059 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642823073 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Gun controlUnited States. | HuntingSocial aspects. | Firearms ownershipUnited States. | FirearmsLaw and legislation United States.

Classification: LCC HV7436.H868 2020 | DDC 363.330973dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

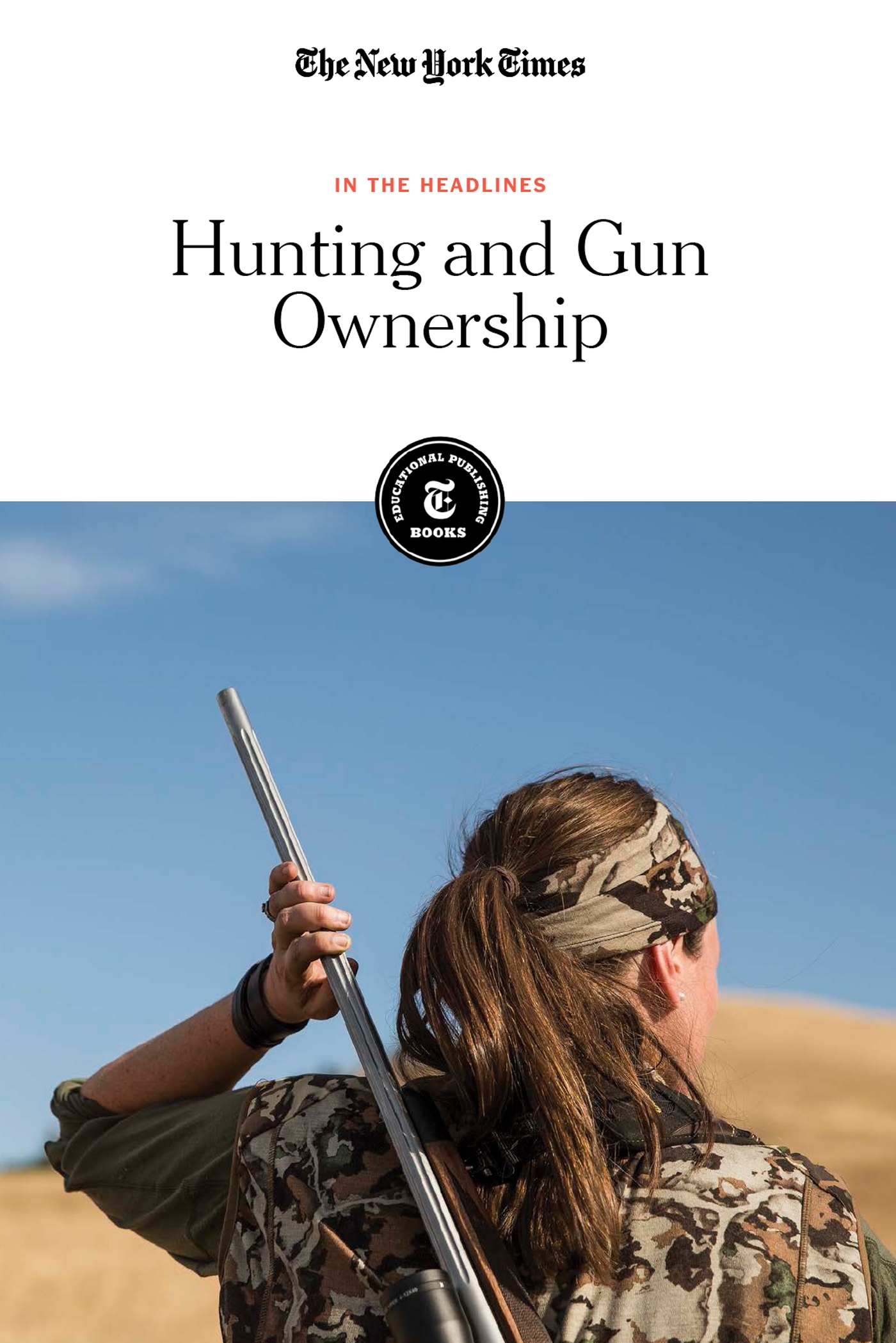

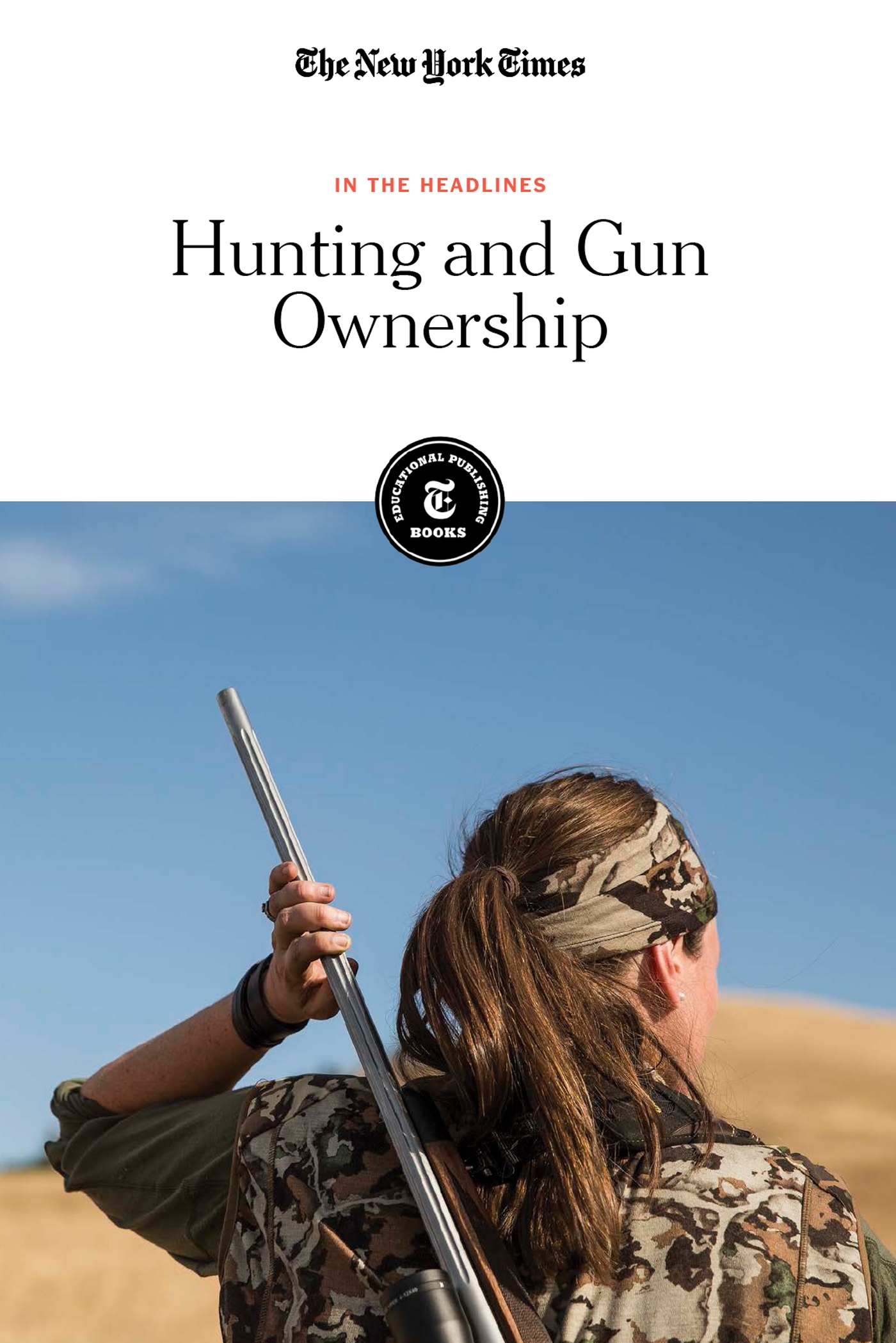

On the cover: Chelsea Cassens during an elk hunt at The Nature Conservancys Zumwalt Prairie Preserve in Imnaha, Ore., Sept. 17, 2018. More and more hunters are making the transition to copper bullets amid mounting evidence that lead bullets are poisoning the wildlife that feed on carcasses and polluting the game meat that many people eat; Max Whittaker/The New York Times.

Contents

Introduction

MANY TRADITIONAL SOCIETIES past, present and on every continent, have viewed the different species in their surrounding environment as participants in the community. The ecological relationships that make up these communities can be helpful or harmful, but the links themselves are ultimately inescapable. All human actions take place in the context of multispecies relationships. One human action that highlights these relationships is hunting, the killing of an animal for food. The practice is a return to some of the oldest foodways of human prehistory, and is for some societies critical for ongoing subsistence.

For societies that have grown distant from their food by agriculture and modern technology, hunting is seen as an opportunity to reconnect not just with their food, but with nature. In the process, hunting becomes a culture, and sometimes an elaborate one, combining scientifically designed hunting gear and collector quality firearms.

The popularity of hunting culture was cultivated by people like Theodore Roosevelt, for whom hunting represented an American ideal. In his time, when the settlement of the United States was drawing to a close and life was rapidly urbanizing, hunting was seen as a way to invigorate American identity. Roosevelt also helped support the budding conservation movement. In the process, hunters assumed some responsibility for preserving the environment, both by carefully controlling animal populations and funding conservation efforts with hunting tags. This relationship between hunting and conservation remains a pillar of many nations environmental efforts.

However, hunting has a political dimension as well. One of the many grievances that led to the French Revolution was the exclusion of peasants from hunting rights enjoyed by the aristocracy. In parallel, many modern indigenous movements in the United States and Canada fight to protect their territorial hunting and fishing rights lost to conquering European settlers. Big game hunts in Africa and Asia still prod old colonial wounds, raising the criticism that some hunts are exclusive to the wealthy. And hunting in American politics is used as an image to court voters, from Roosevelt to Johnson to the present day.

Hunting is often critical in helping or harming the most delicate ecological relationships. It is common knowledge that hunting is a tool for limiting animal overpopulation, but it is less well known that such overpopulation often results from other human activities. In South America and Australia, many recently introduced species are now invasive, requiring hunters to control them. Conflicts in Ukraine have disrupted hunting, allowing growing wolf populations to attack humans. Conversely, international groups are still fighting to break illegal poaching cartels, as elephant and rhino killings have increased. Understanding all forms of hunting, legal and illegal, helps us grasp the complex relationship between society and ecology.

At times, the link between hunting and conservation is challenged. Animal welfare groups, for example, argue frequently against the killing of animals in all forms. Elsewhere, people criticize the practice of trophy hunting in Africa and Asia, making visible the enormous wealth differences between the hunter and the ordinary people living there. Most ecologists see these criticisms as missing the more important ecological role that hunting plays, but the conversation is ongoing.

One especially powerful window into the social-ecological significance of hunting can be found in hunting traditions that have been rooted in a particular place for centuries. Some of these indigenous hunting practices are being abandoned as cultures modernize; others remain vital not just for subsistence but for conservation purposes. For example, Japanese whaling is losing ground, kept alive only by a small political faction fighting for it, while the same practice remains vital for Alaska natives. Likewise, an urbanizing Africa is working to reduce dependence on hunted bush meat, while aboriginal Australians are rediscovering the use of hunting as a conservation tool. While not all indigenous hunting traditions can be expected to persist into the next century, many are important for cultural and ecological preservation.

RENAUD PHILIPPE FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

Cezin Nottaway, an Algonquin who runs a catering business, hunts for deer, partridge and beaver in the forest near her home on the Kitigan Zibi reserve in Quebec. She is committed to preserving her ancestral hunting and cooking traditions.

For many who grew up taking off school for the first day of deer season, some articles in this title will be familiar. This volume includes many stories of waking at dawn, tramping through the elements, waiting in silence with a taut bowstring and pausing with gratitude for the life of a recently slain animal. Other stories focus on the critics and allies of hunting, sportspeople and opportunists, suburbanites with ancient spears and natives with forklifts. But taken together, these stories reflect a sense of wonder at our ecological community and our responsibility for preserving it.

CHAPTER 1

The Beginning of American Hunting Culture

Hunting for recreation emerged as settlement in the American frontier began to end. Many city dwellers began hunting to reconnect with a passing way of life. Politicians like Theodore Roosevelt went on well publicized hunting trips, while also spearheading efforts to protect wildlife. Expanding European empires led to similarly publicized big game hunts in Africa and Asia, practices which continue today. While hunting appeals to Americas frontier tradition, the downside is seen in controversies over Native territorial hunting rights and the loss of species due to overhunting.

Next page