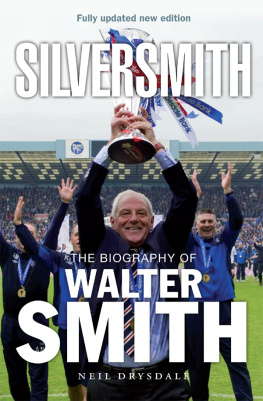

SILVERSMITH

Neil Drysdale has been involved in journalism since the mid-1980s and has been praised for the quality of his writing across a wide range of sports. He was an award-winning writer with Scotland on Sunday for 15 years, but now works freelance, mostly for the Herald and STV. He is the author of three other books Dads Army; the autobiography of Alan Rough; and Dario Speedwagon, a biography of Dario Franchitti. He is married and lives in Aberdeen.

SILVERSMITH

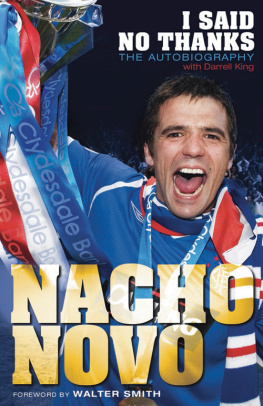

The Biography of Walter Smith

Neil Drysdale

This edition first published in 2011 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Neil Drysdale, 2010

The moral right of Neil Drysdale to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 84158 992 3

eBook ISBN: 978 0 85790 067 8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Designed and typeset by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Craig Brown, Terry Butcher, Ewan Campbell, Ronnie Esplin, Andy Goram, Jim Guy, Sandy Jardine, Ally McCoist, Robert McElroy, Scott Nisbet, Alan Rough, Stephen Smith, Colin Stein, Sandy Tyrie, the Scottish Football Museum and Chick Young. Thanks are also in order to a number of former Rangers players and supporters, who asked for their contributions to remain anonymous, although since the majority of these respondents were expressing praise for Walter Smith, this shyness was sometimes difficult to understand.

I would also like to thank Neville Moir and Peter Burns at Birlinn and my agent, Mark Stanton, for exuding his usual calmness under pressure. Duggie Middleton worked assiduously in editing the original manuscript with his usual diligence. Finally, my wife, Dianne, had to tolerate me deploying my thumping two-finger typing style, often until 4.30 in the morning, and remained a pillar of support throughout the project, for which I thank her.

Neil Drysdale

CHAPTER ONE

A MAN IN THE CROWD

This club is different. This is Rangers Football Club

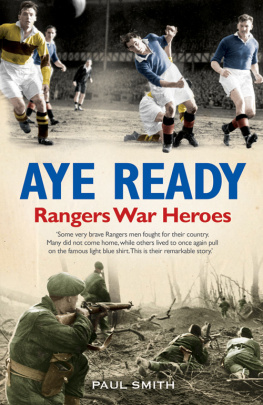

Long before there came Heysel or Hillsborough with their relentlessly grim television images, incongruous floral tributes and uncomprehending vales of tears, there was one Saturday evening in Glasgow on which mothers and fathers, sons and daughters and many friends of friends clung anxiously to the hope that their loved ones would eventually make it home, and confirm that they had escaped the Ibrox Disaster. The majority did come home, and others such as Walter Smith, Alex Ferguson and Andy Roxburgh clambered around the mangled heaps of bodies and stricken souls, the emergency workers and Old Firm volunteers on Stairway 13, and thanked their lucky stars before absorbing the enormity of what had transpired. For 66 other families there was the spectre of a long nights journey into the void, and recognition that the catastrophe which engulfed Ibrox stadium at the end of the New Year match on 2 January 1971, had snatched away their menfolk, and in Margaret Fergusons case, her daughter.

Decades on, pictures from the newsreels reflect collective mystification and bewilderment, accompanied by a sense of futile anger at the casual fashion in which so many lives were sacrificed. But beyond that is a numbness among the grieving families, possibly reflecting their feeling that such hackneyed phrases as Time is a great healer and Theyre in a better place now are but platitudes for those fortunate enough never to have been obliged to identify relatives with faces blackened and life squeezed out of them. Talk to men such as Smith, Sandy Jardine or John Greig hard-nosed artisans from an industrial background and you will not hear easy sentiments, but rather hushed voices and instinctive sympathy for victims who, in other circumstances, could have been their very selves. Then prod them gently on their memories of that ghastly event, and they will relate their accounts of a tragedy which, all too fleetingly, tore through Glasgows sectarian curtain and saw Orangemen shed tears in the company of priests throughout the west of Scotland and yonder into Edinburgh, before snaking across the Forth Bridge to the Kingdom of Fife and the community of Markinch, where Peter Easton, Richard Morrison, David Patton, Mason Phillips and Bryan Todd, schoolboys who lived within a few hundred yards, perished together on that stairway, which had witnessed an accident in 1961 and near-disasters in 1967 and 69.

Sandy Jardine, one of the celebrated ex-players who still walks the corridors of Rangers FC, describes the terrible events:

In these days, this was probably the biggest fixture of the season, considering that the Old Firm clubs only met twice a year, but it was dreadfully ironic that what had been a fairly good-natured occasion, with neither trouble on the terraces nor on the pitch, should develop into a waking nightmare for so many people. Everybody knows the circumstances whereby Jimmy Johnstone sent Celtic in front with a minute to go. The ball got centred, we equalised at once [through Colin Stein] and the referee blew full-time immediately. So you had Rangers supporters who thought: Oh, thats the game over when Jimmy scored turning to go down the big staircase, then turning back when they heard the huge roar which greeted Colins strike, and that coincided with a massive number of spectators making their path towards the exit and the subway. Then suddenly somebody fell, and the whole terrible business began.

The thing is that I was on the ground staff, I had actually swept these stairways, and they were huge, really solid objects, so I could never understand how they could get mangled so badly by any number of human beings. But they were. Just think of it: the pressure of all those bodies cascading over one another and the panic which must have spread... Ach, there are no words in the dictionary to describe adequately what happened during those next few minutes. But you have to realise that we as players were completely unaware anything was wrong at that stage. We were in the dressing room fairly happy to have managed a draw, just sharing a few laughs together before getting into the bath. Well, I was one of the last guys to climb out, but as I re-emerged the order came that there had been an accident, and we all had to leave the room as quickly as possible. It could have been a fire alert or anything, but while we started putting our clothes on as fast as we could, the authorities started to bring some of the dead bodies into the place, and as you can probably imagine, everybody turned grey at the sight of them. But even then we had no real idea of the extent of the fatalities.

As I drove back to my home in the east end of Edinburgh, I heard there were two dead, but soon enough the figures mounted up. It was 12, then 22, then 30, then 44 I dont know why, but that number sticks in my mind and finally it climbed to 66 as the news filtered out to all the parents and kith and kin of the folk who had attended the match, and then gone to pubs or restaurants or picture-houses afterwards. I have spoken to hundreds of fans since 1971, and they have told me of how vast crowds assembled at all of the drop-off points for the buses to find out whether their loved ones were okay. The telephone lines were jammed, Glasgow was in turmoil, the hospitals were all packed to overflowing. Anxiety, terror, pain, sadness, horror... a blanket of all these emotions was draped over the whole country that night, but there was nothing remotely comforting about it.

Next page