16/18 Woodford Rd.

Names: Feldman, Andrew, 1973- author.

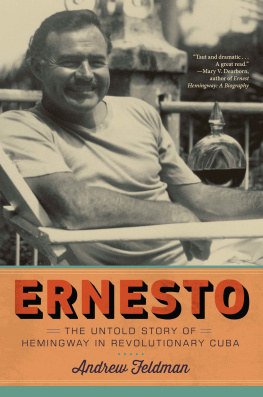

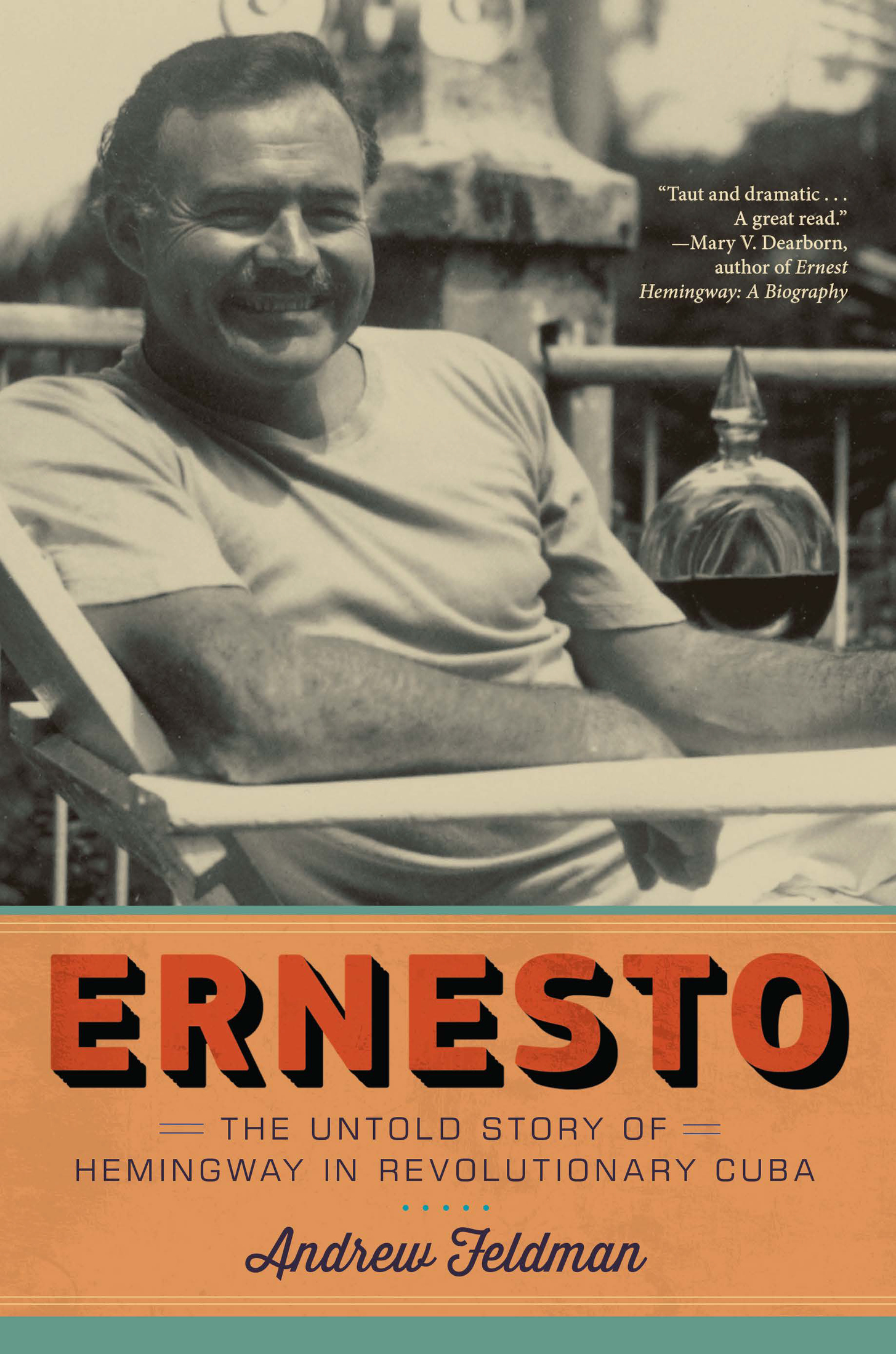

Title: Ernesto : the untold story of Hemingway in revolutionary Cuba / Andrew Feldman.

Description: Brooklyn : Melville House, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018050528 (print) | LCCN 2018055010 (ebook) | ISBN 9781612196398 (reflowable) | ISBN 9781612196381 | ISBN 9781612196381 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781612196398 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Hemingway, Ernest, 1899-1961Homes and hauntsCuba. | Hemingway, Ernest, 1899-1961KnowledgeCuba. | Authors, American20th centuryBiography. | AmericansCubaBiography.

Classification: LCC PS3515.E37 (ebook) | LCC PS3515.E37 Z5897 2019 (print) | DDC 813/.52dc23

INTRODUCTION

Along the windswept banks of a fishing village a few miles from Havana, there is a bust dedicated to the memory of a writer, set there by its inhabitants, the fishermen of Cojmar. When they first heard the news that Hemingway was dead, it felt as if they had received a blow from the long beam of their sail as wind changed and the boat came suddenly about. Still, some of them doubted the validity of the news; after all, the papers had declared his death on more than one occasion and were obliged to retract their stories when Mr. Way (as many of the fishermen, finding his full name difficult to pronounce, called him) returned from the dead, indestructible and immortal, like some hero of ancient lore. Others, sneering at the headlines, rejected the suggestion, repeating itself like a vulgar joke in the newspapers and on the radio, that his death had been a suicide. In this way, they were able for a time to maintain the fiction that their friend, Ernest Hemingway, was alive and that he had never faltered in the face of death.

For thirty years, the villagers had shared the sea and fished with Hemingway, so they believed that they knew him well. They came to love him naturally and simply, like a brother, as was their custom, and he came to love them back. Whenever he, in his motored craft, encountered them after a long day of fishing, rowing back beneath the sun, el americano would throw out a line and tow their boats back to port. Often, he would invite them for a drink in La Terraza, the village restaurant-bar beside the docks where they could talk, exchange tips about sea conditions, and enjoy some rum and one anothers company. Asking many questions, Ernest Hemingway, the writer, listened intently to their responses, to their sentiments, and to their manner of speakingslowly gathering details for his work and strengthening ties of friendship with these men.

In Cojmar where his first mate Gregorio Fuentes also lived, Hemingway kept his boat, the Pilar. It was safe there. Everyone in the village knew who owned it, and they looked after it as if it were their own. As the years passed, he had become part of their community; when Gregorio Fuentess daughters married, Hemingway, along with the other fishermen, attended their weddings.

H emingways experiences in Cojmar provided the material that allowed him to write the novel that rescued his career and restored his readers faith in his astonishing talent. His previous novel, Across the River and into the Trees, had been considered a failure. This awkward work of fiction indulgently explored two of his infatuations: his World War I wounds and nineteen-year-old Venetian beauty Adriana Ivancich, with whom he had become enamored while deep in the throes of a middle-age crisis. The book was ill received by both the public and his critics, who ridiculed its self-indulgent style, gossiped about the disgraceful goings-on of its aging author, and declared his career over. Like a counterpunch, Hemingway then released a much shorter work, over a decade in the making, condensing his experiences accumulated during a lifetime of fishing the Gulf Streamwith the fishermen he had come to admire. He called this novella, about an aging fisherman and his Cuban village of Cojmar, The Old Man and the Sea.

The work achieved immediate success and widespread praise from many of the very critics who had so roughly criticized his previous work. It won him a Pulitzer Prize and, one year later, resulted in the achievement of literatures highest honor, the Nobel Prizesolidifying his place as a literary legend. Recognizing his debt to the village and to Cuba, Hemingway immediately announced to the press that he had won the prize as a citizen of Cojmaras a Cubano sato. His gift not only underlined his gratitude but also suggested that, after twenty-two years of residence in Cuba, Hemingway believed in La Virgen too.

In the pages of Life magazine, The Old Man and the Sea first appeared with pictures of Hemingway walking along the shores of Cojmar village on its cover. Warner Brothers offered Hemingway $150,000 for the movie rights and another $75,000 to serve as the films technical advisor, an unprecedented sum for a writer to receive in 1953. Drawing from the films $5 million budget, the author also insisted upon employing all of Cojmars fishermen to assist in the production, in order to lend the film some authenticity, to recognize them, and to bring their struggling families some much-needed income.

Hemingway Dead of Shotgun Wound; Wife Says He Was Cleaning Weapon, said the newspaper, which Cojmars fishermen read before wrapping it around the baitfish that they would bring on the boat that day. Reflecting upon it, they saw Marys denial was merely her grief, and after long hours spent at sea, the realization that they were also grieving floated slowly to the surface. When they returned to port and observed his ship, the Pilar, anchored there, floating without a captain, their throats thickened from the emptiness, for they understood they missed a friend and a man that they had admired. They could not bring themselves to judge this man that they respected and loved. Gathering at La Terraza, they stood silently along the bar where their friend no longer appeared. But they wanted to do something more to honor him.

They decided to commission a sculpture and place it at the entrance of the harbor of their town. They were very poor, and they did not have enough money to purchase the material, so they melted down the propellers from their boats for a sculptor to fashion into a bust. Today the bust remains, its eyes fixed forever, gazing into the waters of the Gulf, a source of life and mystery that the writer loved and so often wrote about.