THE GOOD LIFE

ACCORDING TO

HEMINGWAY

EDITED BY

A. E. HOTCHNER

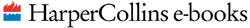

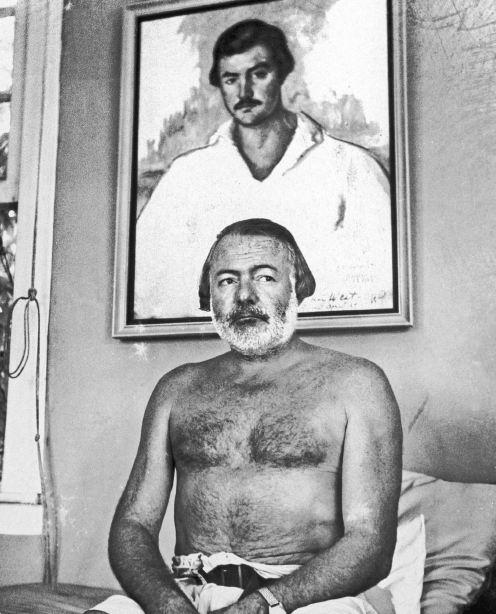

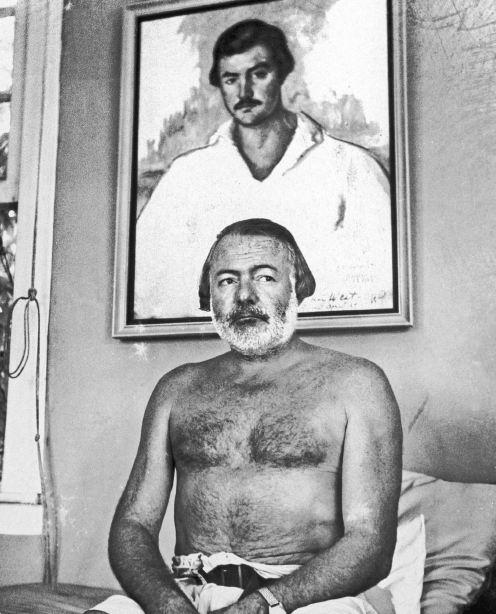

At Finca Viga.

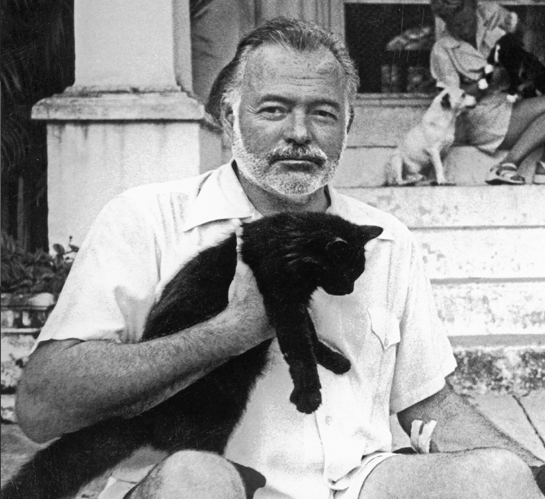

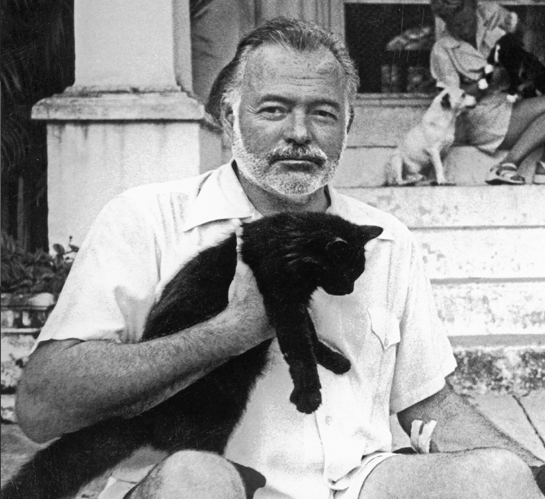

On safari with white hunters, Philip Perceval (at left), and his son, Richard.

To the memory of my good friend

Jack Hemingway

CONTENTS

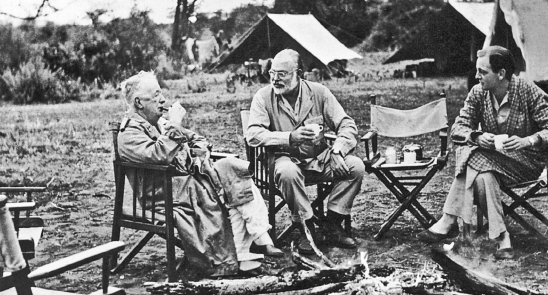

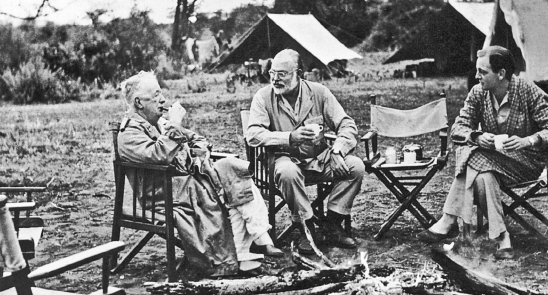

Hunting with Hotchner, Ketchum, Idaho, 1956.

I first met Ernest Hemingway in the winter of 1948, when, as a literary bounty hunter, I was sent by a magazine to Havana to ask him to write an asinine essay. I had become a bounty hunter because, at the conclusion of my four-year service in the Air Force, bloated with severance pay, I had elected to be discharged in Paris, where the dollar ruled supreme and where I was enjoying a romantic relationship with a young lyric soprano of the Paris Opera who had proposed cohabitation at her place in Neuilly.

The only problem with this nirvana was that while I was reveling in my Paris excesses, the editorial jobs that possibly could have been mine were quickly being filled by diligent military personnel who had been promptly discharged in the States. My friend Arthur Gordon, who had been in the Air Force with me, had become editor of Cosmopolitan, then a reputable literary magazine, before its corruption by Helen Gurley Brown, during my two years of Parisian frolic had several times offered me an editorial position, but when I finally did return to the States, my finances having dwindled to the price of a cabin-class ticket on the Ile de France, neither Arthur nor any other editor had an opening for ex-Major Hotchner, lately a bon vivant of avenue Neuilly.

Faced with the alarming prospect of having to return to the St. Louis law firm from which my draft board had extricated me, Arthur, a very compassionate man, out of pity invented a job for me: he gave me a list of writers who had written for Cosmo during its long, illustrious past, with the understanding that I would seek them out and attempt to induce them again to contribute to the magazine. The list was intimidating: Dorothy Parker, Sinclair Lewis, John Steinbeck, Edna Ferber, James Thurber, Pearl Buck, Fannie Hurst, Ernest Hemingway, John OHara, William Faulkner, Robert Benchleya roll call of the most important writers of their time. My remuneration would be expenses plus a $300 bonus for every writer I bagged. It wasnt much, but it was either skimp along on that, or slink back to St. Louis and that affiliation I had grandly renounced (after less than two years of practice) with the firm of Taylor, Mayer, Shifrin and Willer.

At first it was daunting to contact the prestigious names on my bounty list and convince them to write something for old times sake, but to my surprise, I found that writers of their stature were almost never invited to write for specific publications; rather, they sent their compositions to their agents or directly to their publishers. Famous though they were, some of those on my list were flattered by the attention, and as a result I did have some success. Dorothy Parker, sadly in need of income, not only wrote a short story about a deadly game of charades, but remained a good friend until her death many years later. Edna Ferber had been frozen (her word) since the atrocities in Germany, but she too broke the ice and wrote a story; like Dorothy, she continued to stay in touch with me for years afterward. In fact, a few months after our initial meeting at her apartment in the Sherry-Netherland in New York City, she invited me to a memorable dinner she hosted, which was attended by George Kaufman, Moss Hart, Alexander Woollcott, Kitty Carlisle, Groucho Marx, Mary Astor, Helen Hayes, and Robert Benchley. Of those on my bounty list, only John OHara and William Faulkner dismissed me abruptly.

The one name on the list I did not attempt to contact was Hemingway. For me, he was more formidable than the others, not only as a writer but also as a prestigious member of the celebrity echelon of that time. His exploitsshooting wild beasts on safari, fishing the high seas, involving himself in the world of bullfightingwere widely covered in the media, often with considerable exaggeration. (As I write this, I am reminded of an incident that occurred years later when we were having a drink at the bar of the Stork Club, prior to being seated in the exclusive Cub Room by the proprietor, Sherman Billingsley. An inebriated gentleman detached himself from his group at the end of the bar and swayed over to Hemingway, his drink hoisted in toast position. You know who the three most important people in America are? he asked slurringly. General Eisenhower, Ernest Hemingway, and Tom Collins!)

I had been in awe of Hemingway ever since Hilda Levy my high school English teacher, introduced me to Hemingways autobiographical Nick Adams stories. My favorite was a story called The Battler, which, as it turned out, I was destined to dramatize twenty years later for NBCs Playwrights 56, which initiated me as a playwright, as well as the young actor Paul Newman, who played the lead. I had read all of Hemingways books and seen the movies allegedly based on them. In fact, during the war, I had seen For Whom the Bell Tolls, starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman, in a hangar in Tripoli where my outfit, the 13th Wing of the Air Force AntiSubmarine Command, was stationed.

Why havent you contacted Ernest Hemingway? Arthur wanted to know. Cosmo ran a section of To Have and Have Not in advance of its publication, so were on friendly grounds.

But, Arthur, you want me to ask him to write an article on the future of literatureI cant ask the great Hemingway to write something as dumb as that. Hell level me.

Its part of a seriesFrank Lloyd Wright on the future of architecture, Eugene ONeill on drama, Henry Ford II on automobiles, Balanchine on ballet, and so forth. Distinguished company. Dont be a coward. Get your freckled ass down to Cuba or youll be back in St. Louis with your nose buried in a Corpus Juris Secundum.

When I arrived in Havana in 1948, I took the cowards way out and wrote a note to Hemingway, telling him that I was there on an embarrassing assignment, to request that he write an article on the future of literature. Would he please send me a turndown so I could keep my miserable job at Cosmopolitan? I arranged for a messenger from the Nacional Hotel, where I was staying, to deliver my note to Hemingways place in San Francisco de Paula, a little village on the outskirts of Havana.

That afternoon, the phone in my room rang and a hearty voice said, This Hotchner? Dr. Hemingway here. Got your note. Cant let you abort your mission, or youll lose face with the Hearst organization, which is about like getting bounced from a leper colony. You want to have a drink around five? Theres a bar called La Florida. Just tell the taxi.