Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR MY WIFE

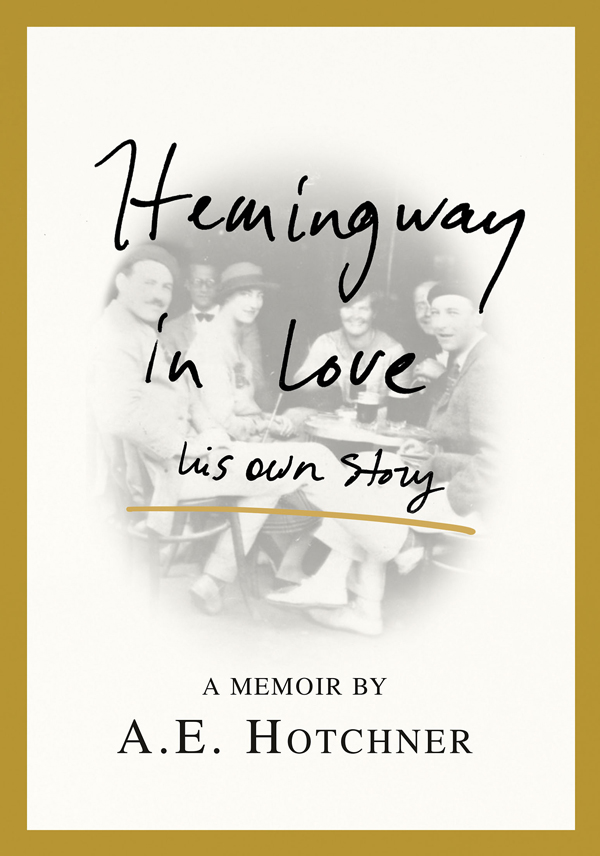

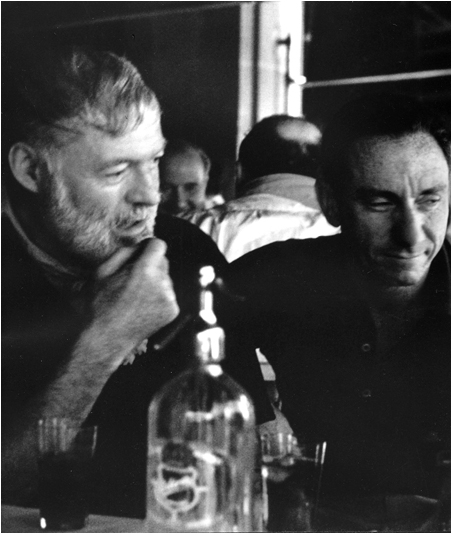

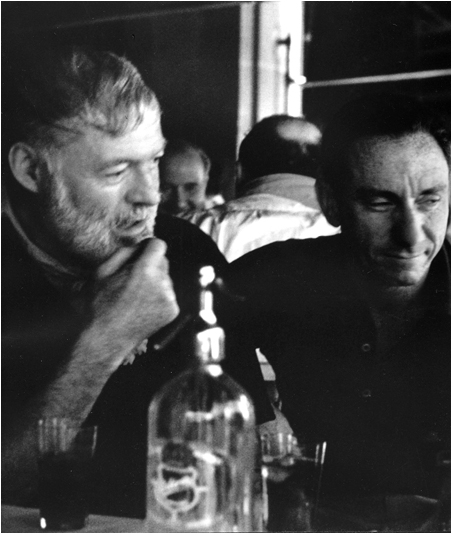

Pamplona, Spain, 1954: Ernest and Hotchner at El Choko bar during La Feria de San Fermn.

All things truly wicked start from an innocence.

ERNEST HEMINGWAY

Fifty years ago, a few years after Ernest Hemingways death, I wrote Papa Hemingway, an account of our thirteen years of adventures and misadventures. For those who may not have read it in Papa , I am again referring to the spring of 1948, when I was dispatched to Havana on the ridiculous mission of asking Hemingway to write an article on The Future of Literature. I was with the magazine Cosmopolitan, then a literary magazine, before its defoliation by Helen Gurley Brown, and the editor was planning an issue on the future of everything: Frank Lloyd Wright on architecture, Henry Ford II on automobiles, Picasso on art, and, as I said, Hemingway on literature.

Of course, no writer knows the future of literature beyond what hell write the next morning, if that, but there I was, checking into the Hotel Nacional for the express purpose of knocking on Hemingways door and asking him to read his literary tea leaves for good old Cosmo. I had tried to avoid this obnoxious assignment, but I was on a go do it or else basis, and I could not afford an or else as I had been but six months on the job, the only one I had been able to land after dissipating my air force severance pay with a frivolous year in Paris.

As a compromise I took the cowards way out and wrote Hemingway a note, asking him to please send me a brief refusal, which would be very helpful to The Future of Hotchner.

Instead of a note, I received a phone call the next morning from Hemingway, who proposed five oclock drinks at his favorite Havana bar, the Floridita. He arrived precisely on time, an overpowering presence, not in height, for he was only an inch or so over six feet, but in impact. Everyone in the place responded to his entrance.

The two frozen daiquiris the barman placed in front of us were in conical glasses big enough to hold long-stemmed roses.

Papa Doblas, Ernest said, the ultimate achievement of the daiquiri makers art. He conversed with insight and rough humor about famous writers, the Brooklyn Dodgers, who were there for spring training, actors, prizefighters, Hollywood phonies, fish, politicians, everything but The Future of Literature. He left abruptly after our fourth or fifth daiquiriI lost countbut I was able to retain in the rum mist of my head that he was going to pick me up at six oclock the next morning and take me on a tour around the Morro Castle waters in his boat, the Pilar. When I got back to the hotel, despite the unsteadiness of my pen, I was able to make some notes of our conversation on a sheet of the hotels stationery. For all the time I knew him, I made a habit of scribbling entries about what had been said and done on any given day. Later on, I augmented these notes with conversations recorded on my Midgetape, a minuscule device the size of my hand, whose tapes allowed ninety minutes of recording time. Ernest and I sometimes corresponded by using them. Although the tapes disintegrated soon after use, I found them helpful.

* * *

Steering from topside controls, Ernest took the Pilar several hours up the coast. On the way back, we hooked what he referred to as a stunted marlin, but to me it looked like an unstunted whale. He strapped me into the catch chair and handed me the big heavy rod and reel that had the marlin on the other end. I had never caught anything bigger than a ten-pound bass out of a rowboat and I probably would have had a tough struggle, perhaps even losing the marlin, but Ernest guided me every step of the way, from when to pull up to set the hook to when to bring him in to be taken. The thrill of having reeled in this monster was muted, however, when Ernest and his mate, Gregorio Fuentes, unhooked the marlin and set him free.

We just might have a new syndicat des pecheurs, he said jokingly, Hotchner and Hemingway, Marlin Purveyors. That took the sting out of not having my picture taken on the dock with the marlin, stunted or not, hanging by its tail beside me.

Over the ensuing years, I would observe Ernests gentle patience with young people like myself innumerable times. He interacted with them easily. In my case, for example, although I had had military training in firearms, I was a flop at wing shooting, but Ernest patiently led me to proficiency in jump-shooting mallards soaring from canals at the base of the Sawtooth Mountains in Idaho, and cock pheasants breaking from the cornfields. The more our friendship grew, the more I realized that the stories that had circulated about his gruff, pugnacious personality were a myth invented by people who didnt know him but judged him by the subjects he wrote about. He would stand up to any transgressor, yes, but I never saw him as the aggressor.

* * *

When we returned from the boat to the Nacional and were saying good-bye in front of the hotel, Ernest said, mentioning it for the first time, The fact is, I do not know a damn thing about the future of anything.

I assured him it was a dumb request.

He asked what they were paying, and when I said ten thousand dollars, he said well, that was enough to perk up The Future of Something, perhaps a short story, and that we should stay in touch.

We did for the next eight months, culminating in his informing me that he was at work on a novel, which I eventually edited for the magazine. In the process, I accompanied Ernest and his wife, Mary, to Paris and Venice to corroborate the details of certain sections of the novel, Across the River and into the Trees, and that was the beginning of our friendship, which over the years took us adventuring to his favorite haunts: hunting for pheasant, wild duck, and Hungarian partridge in Ketchum; bullfighting in Madrid, Mlaga, Zaragoza, and the mano a mano competitions of the great matadors Antonio Ordez and Luis Miguel Domingun; deep-sea fishing for marlin; jai alai matches in Havana; the Auteuil steeplechases in Paris; the World Series and championship prizefights in New York, to name a few.

But looking back on those years, there was one event that seriously interrupted our adventuring: the consecutive plane crashes that Ernest suffered in the African jungle. He had been subjected to a near-death experience in the second of those crashes; that experience upended him, and he was determined to tell me about a painful period in his life that he had never discussed but that he wanted me to know about in case he never got around to telling about it.

Over the following years, while we traveled, he relived the agony of that period in Paris when he was writing The Sun Also Rises and at the same time enduring the harrowing experience of being in love with two women simultaneously, an experience that would haunt him to his grave.

Some of these intimate revelations were contained in my original Papa Hemingway manuscript, but when, before publication, the publisher, Random House, submitted the script pro forma to their lawyers for vetting, the lawyers put the script through their cautious legal wringer, and as a result, those people involved who were still living had to be stricken. In questioning me about the people depicted, the lawyers even went so far as to require proof that F. Scott Fitzgerald, twenty years dead, was indeed gone.