Also by Patrick Leigh Fermor

The Travellers Tree (1950)

The Violins of Saint-Jacques (1953)

A Time to Keep Silence (1957)

Mani (1958)

Roumeli (1966)

A Time of Gifts (1977)

Between the Woods and the Water (1986)

Three Letters from the Andes (1991)

Words of Mercury (2003) edited by Artemis Cooper

In Tearing Haste: Letters between Deborah Devonshire and Patrick Leigh Fermor (2008)

The Broken Road (2013)

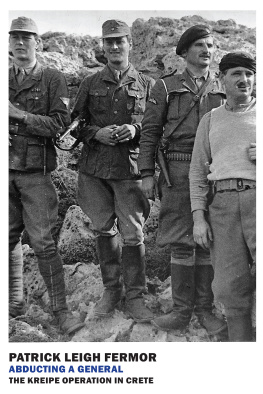

Abducting a General (2014)

TRANSLATED AND EDITED

The Cretan Runner by George Psychoundakis

Also by Adam Sisman

A. J. P. Taylor: A Biography (1994)

Boswells Presumptuous Task (2000)

The Friendship: Wordsworth and Coleridge (2006)

Hugh Trevor-Roper: The Biography (2010)

One Hundred Letters from Hugh Trevor-Roper (2013)

with Richard Davenport-Hines

John le Carr: The Biography (2015)

Patrick Leigh Fermor

A Life in Letters

Selected and edited by Adam Sisman

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Letters of Patrick Leigh Fermor copyright 19402010 by the Estate of Patrick Leigh Fermor Compilation, notes, introduction, and editorial matter copyright 2016 by Adam Sisman

All rights reserved.

First published in Great Britain in 2016 by John Murray (Publishers), an Hachette UK Company

Cover illustration by Nathan Gelgud

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fermor, Patrick Leigh, author. | Sisman, Adam, editor.

Title: Patrick Leigh Fermor : a life in letters / Patrick Leigh Fermor ; selected and edited by Adam Sisman.

Description: New York : New York Review Books, 2017. | Original title: Dashing for the Post

Identifiers: LCCN 2017014756| ISBN 9781681371566 (paperback) | ISBN 9781681371573 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Fermor, Patrick Leigh,Correspondence. | Travel writersGreat BritainCorrespondence. | SoldiersGreat BritainCorrespondence. | BISAC: LITERARY COLLECTIONS / Letters. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Literary. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Adventurers & Explorers.

Classification: LCC PR6056.E65 Z48 2017 | DDC 910.4092 [B]dc23LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017014756

ISBN 978-1-68137-157-3

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

In memory of Robyn Sisman

Contents

Introduction

The letters in this volume span seventy years, from February 1940 to January 2010. The first was written ten days before Patrick Leigh Fermors twenty-fifth birthday, when he was an officer cadet, hoping for a commission in the Guards. He had hurried back to England from Rumania in September 1939, expecting to die within weeks of being sent into action, like a junior officer in the First World War. The last two were written on the same day in 2010, when Paddy (as he called himself, and almost everyone else called him) was ninety-four, a widower, very deaf, and suffering from tunnel vision, which made it hard for him to read even his own handwriting. His voice was already hoarse from the throat cancer which would kill him seventeen months later. But these last letters, like the first and most of the others printed here, exude a zest that was characteristic. From first to last, Paddys letters radiate warmth and gaiety. Often they are decorated with witty illustrations and enhanced by comic verse. Sometimes they contain riddles and cringe-causing puns.

Although, as I have mentioned, he was only twenty-four when he wrote the first letter in this volume, one of the two achievements for which he is best known was already behind him. Paddy had set out at the age of eighteen to walk to Constantinople (as he called it), after a premature exit from his boarding school (which would honour him later in life as a free spirit). He left England early in December 1933, and arrived at his destination just over twelve months later, on New Years Eve 1934. In the course of this Great Trudge across Europe, he slept under the stars and in schlosses, dossed down in hostels, awoke more than once with a hangover in the houses of strangers, sat round a campfire singing songs with shepherds, frolicked with peasant girls and played bicycle polo with his host. He observed customs and practices that dated back to the Middle Ages, many of which were about to vanish for ever swept away, first by the catastrophe of war and then by Communism. As Paddy puts it in one of these letters, a sudden Dark Age descended that nobody was ready for. He would give an account of his experiences in what became a trilogy of much admired books, which remained incomplete at his death: A Time of Gifts (1977), Between the Woods and the Water (1986), and the posthumously published The Broken Road (2013).

Paddy would spend the late 1930s oscillating between Greece, Rumania, France and England. In the late summer of 1938, before leaving for Rumania, he left with a friend in London two trunks, which were subsequently lost with their contents, among them notebooks he had kept on his walk and letters home to his mother. The loss helps to explain why there are no pre-war letters in this volume. Nor are there more than a couple from the war itself. Rather than going into the Guards, which had rated his capabilities as below average, Paddy had been snapped up by the Intelligence Corps, on the basis of the fact that he spoke German, Rumanian and Greek; and after being evacuated first from mainland Greece and then from Crete as the Germans invaded, he had been infiltrated back on to Crete to operate under cover, liaising with the local resistance. It was during this period, as Paddy made regular clandestine visits to German-occupied Crete from his base in Cairo, that he planned and executed the abduction of an enemy general, the other achievement for which he is best known. The second letter in this volume, written to the mother of his second-in-command, Billy Moss, refers to this daring exploit, albeit discreetly.

After the war Paddy worked for the British Council in Athens for just over a year his only period of peacetime employment, as it would turn out, which ended in his dismissal. It became quickly apparent that he was unfit for office work. Included here is a letter written during a lecture tour of Greece undertaken on behalf of the British Council, and another to Lawrence Durrell in which he complains at being let go, prompting a rare lapse into profanity.

The rest of his long life was spent as a writer. Before the war he was already pursuing literary projects, and had translated a novel from French into English; after leaving the British Council, he accepted an invitation to write the captions for a book of photographs of the Caribbean, a task that grew into a full-length book, The Travellers Tree, published in 1950. (Paddy would invariably exceed any word limit he was given, just as he could never keep to a deadline.) From then on, though often short of money, he seems never to have considered any other form of work. His experiences in the Caribbean inspired him to write a novel (his only work of fiction), The Violins of Saint-Jacques (1953). He was already working on a book drawing on his travels in Greece, part autobiographical, part ethnographical, which grew into two volumes: Mani (1958) and