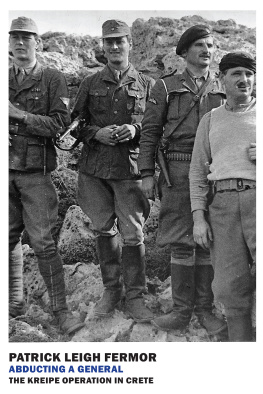

PATRICK LEIGH FERMOR (19152011) was born of Anglo-Irish descent and raised in Northamptonshire and London. After his stormy schooldays, followed by the walk across Europe to Constantinople that begins in A Time of Gifts (1977) and continues through Between the Woods and the Water (1986), he lived and traveled in the Balkans and the Greek Archipelago. His books Mani (1958) and Roumeli (1966) attest to his deep interest in languages and remote places. In the Second World War he joined the Irish Guards, became a liaison officer in Albania, and fought in Greece and Crete. He was awarded the DSO and OBE. He lived until the end of his life in the house he designed with his wife Joan in an olive grove in the Mani. He was knighted in 2004 for his services to literature and to BritishGreek relations.

KAREN ARMSTRONG, a historian of religion, spent seven years in a Roman Catholic religious order; she has written about this experience in Through the Narrow Gate and The Spiral Staircase. She is also the author of many books, including A History of God, The Great Transformation, and, most recently, The Bible: A Biography.

Other books by Patrick Leigh Fermor

Published by New York Review Books

A Time of Gifts

Between the Woods and the Water

Mani

Roumeli

The Traveller's Tree

A TIME TO KEEP SILENCE

PATRICK LEIGH FERMOR

Introduction by

KAREN ARMSTRONG

Drawings by

JOHN CRAXTON

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

W HEN Patrick Leigh Fermor walked up the hill to the Abbey of St. Wandrille de Fontanelle in northern France seeking a quiet, cheap place in which to write, he entered a territory that was alien in a different way from the remote places he had described in his other travel books. Indeed, as he soon discovered, the monastery represented another world, one that entirely and deliberately reversed the norms of secular life. I had a similar experience when I entered a convent as a young girl. To an outsider, the life of monks and nuns seems forbidding and even perverse, but for centuries it has exerted an irresistible appeal, not only in Western Christendom but in almost all cultures and religious traditions.

The monastic life is so at odds with the outside world that it often inspires immense hostility. As Leigh Fermor notes repeatedly, the ruined buildings of the great abbeys and convents of Europe recall the savagery of the kings and reformers who so repeatedly razed them to the ground. Even today, people often feel affronted by the lifestyle of monks and nuns, which challenges so many of our more secular values and seems inhuman, inhumane, and joyless. Instead of seeking wealth, comfort, and material success, monks opt for poverty and do not even own their own toothbrushes. Their voluntary celibacy and renunciation of intimacy seem to violate basic human instincts in a world that lays such emphasis on family values. And, hardest of all, perhapsthough this is something Leigh Fermor does not explorethey give up their freedom and personal autonomy, vowing obedience to their superiors in a way that is repugnant to the independent ethos of modernity. And yet people continue to choose this austerity. As Leigh Fermor shows, even though their abbeys were destroyed again and again, the orders always came back and resumed the disciplines that brought the monks a peace and fulfillment that they could not find in the outside world.

Monasticism tells us something important about the structure of our humanity. Almost every single one of the major world traditions has developed some form of coenobitic life. Just as some peopleat all times and in all cultureshave felt impelled to become dancers, poets, or musicians, others are irresistibly drawn to a life of silence and prayer. They have an unusual talent, by no means granted to all the faithful, for meditation, and they will never be satisfied unless they are able to develop and practice it assiduously. The athlete and the dancer reveal the potential of the human body; they willingly subject themselves to a painful, rigorous, and exhausting discipline, giving up many comforts and pleasures in order to learn their craft. Because of this dedication, they are able to perform physical feats that are beyond the reach of an untrained person. In the same way, the contemplative gladly submits to an equally demanding regimen and, once he or she has become adept, manifests the full potential of the human spirit.

It is significant that the monastic life follows a similar pattern all the world over. People have found, by trial and error, that certain practices are efficacious and that others are not. The monks monotonous way of life has been deliberately designed to protect them from the distractions of, and the lust for, novelty: they do the same things day after day; they dress alike and shun individuality and personal style. They keep almost perpetual silence, so that their attention is directed within. They chant their scriptures together, so that the sacred texts become a part of their inner landscape. Community life is very important because the experience of living with people whom they have not chosen and may not find congenial gradually erases the selfishness that will pre-vent them from attaining the transcendent experience they seek.

The monastic life demands a kind of deaththe death of the ego that we feed so voraciously in secular life. We are, perhaps, biologically programmed to self-preservation. Even when our physical survival is not in jeopardy, we seek to promote ourselves, to make ourselves liked, loved, and admired; display ourselves to best advantage; and pursue our own interestsoften ruthlessly. But this self-preoccupation, all the world religions tell us, paradoxically holds us back from our best selves. Many of our problems spring from thwarted egotism. We resent the success of others; in our gloomiest, most self-pitying moments, we feel uniquely mistreated and undervalued; we are miserably aware of our shortcomings. In the world outside the cloister, it is always possible to escape such self-dissatisfaction: we can phone a friend, pour a drink, or turn on the television. But the religious has to face his or her pettiness twenty-four hours a day, three hundred and sixty-five days a year. If properly and wholeheartedly pursued, the monastic life liberates us from ourselvesincrementally, slowly, and imperceptibly. Once a monk has transcended his ego, he will experience an alternative mode of being. It is an ekstasis, a stepping outside the confines of self.

The ascetics of India have pursued the same goal and their way of life is remarkably similar to that of Christian monks. They designed the disciplines of yoga, for example, precisely to take the I out of their thinking. They thus acquired a new vision, finding that once it was no longer regarded self-referentially, even the humblest object revealed a numinous quality. Yogins train themselves to do the opposite of what comes naturally: they learn to sit without the motion that is a sign of life, as though they were statues or plants; they control their respiration, the most reflexive of our bodily functions; and they learn to curb the stream of restless thoughts that ceaselessly invade the human mind. When they have transcended the condition of normal, secular consciousness, they experiencethe texts tell usthe indescribable joy and liberation of Nirvana. A Christian monk might say that they come into the presence of God.