Also by Patrick Leigh Fermor

The Travellers Tree

The Violins of Saint-Jacques

A Time to Keep Silence

Mani

Roumeli

A Time of Gifts

Between the Woods and the Water

Three Letters from the Andes

Words of Mercury, edited by Artemis Cooper

In Tearing Haste: Letters Between Deborah Devonshire and

Patrick Leigh Fermor, edited by Charlotte Mosley

Translated and edited

The Cretan Runner by George Psychoundakis

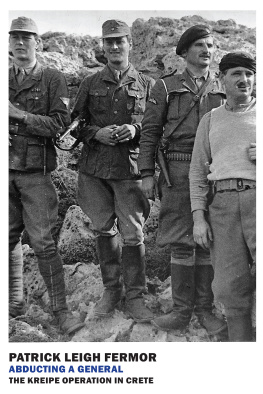

Abducting a General

The Kreipe Operation in Crete

PATRICK LEIGH FERMOR

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS, NEW YORK

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Text Copyright 2014 by the Estate of Patrick Leigh Fermor

Foreword and notes copyright 2014 by Roderick Bailey

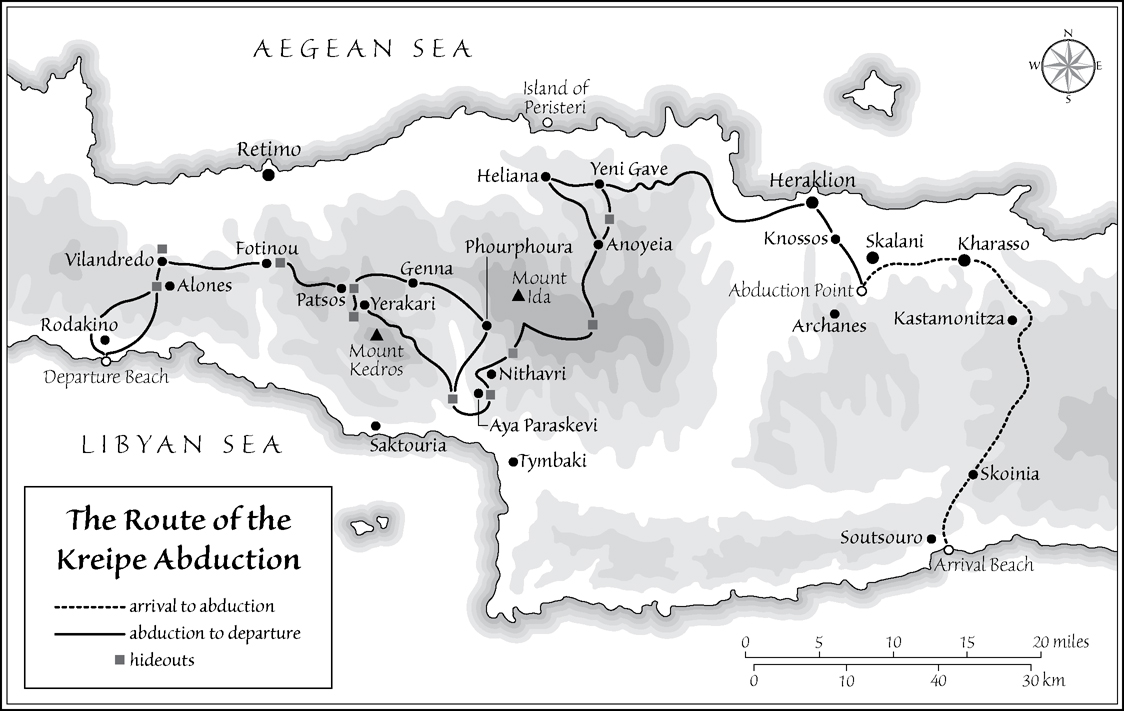

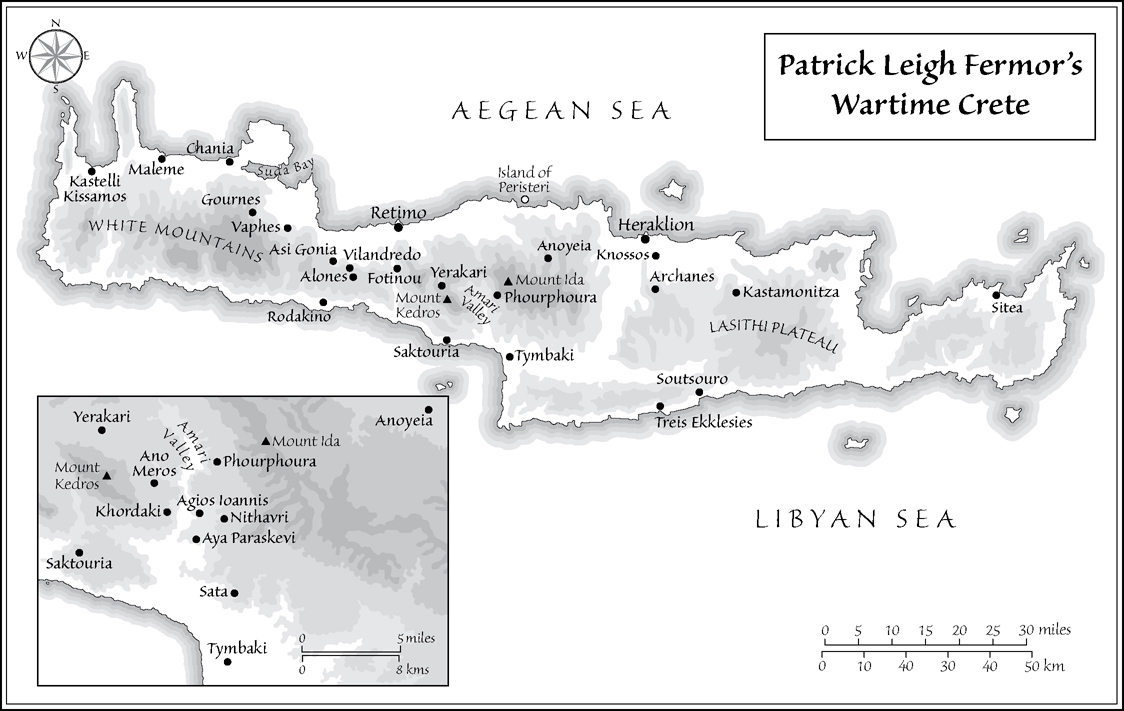

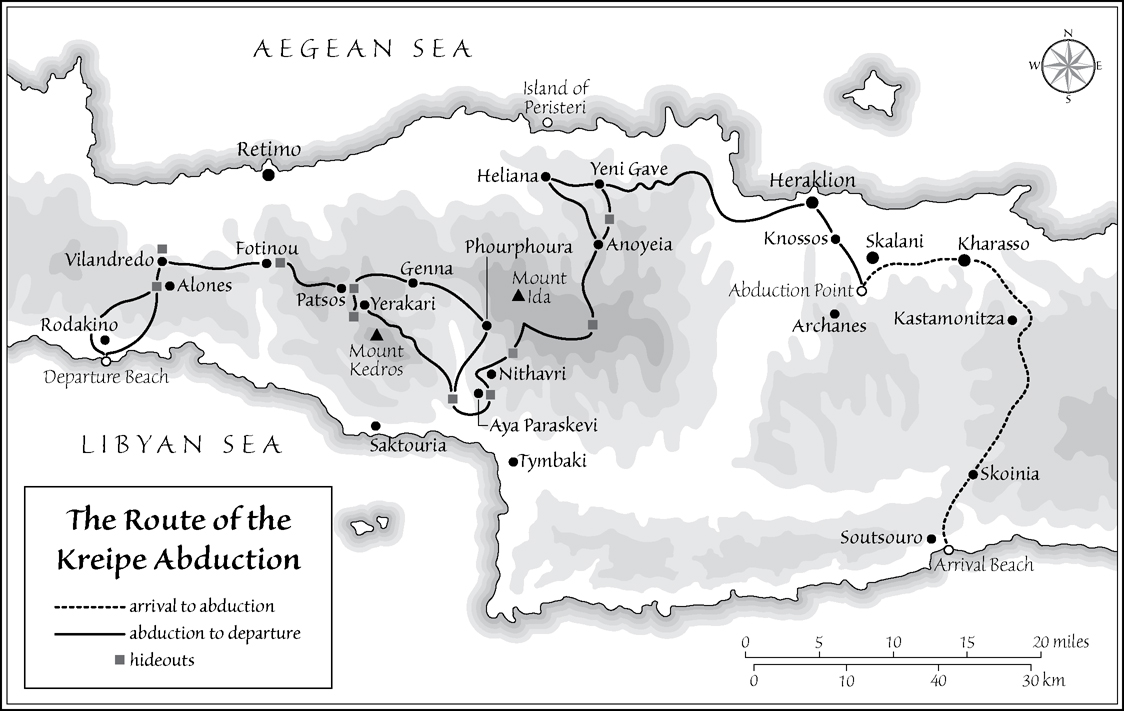

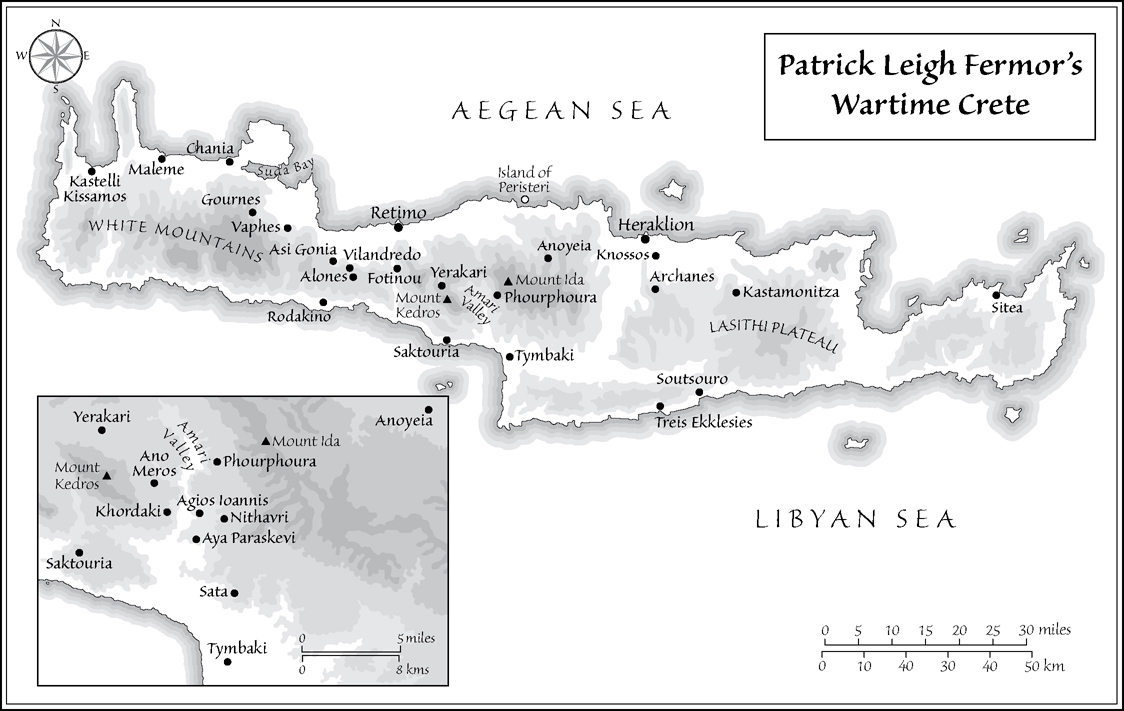

Guide to the Abduction Route 2014 by Chris White and Peter White

All rights reserved.

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

John Murray (Publishers), an Hachette UK Company

Maps by Rodney Paull

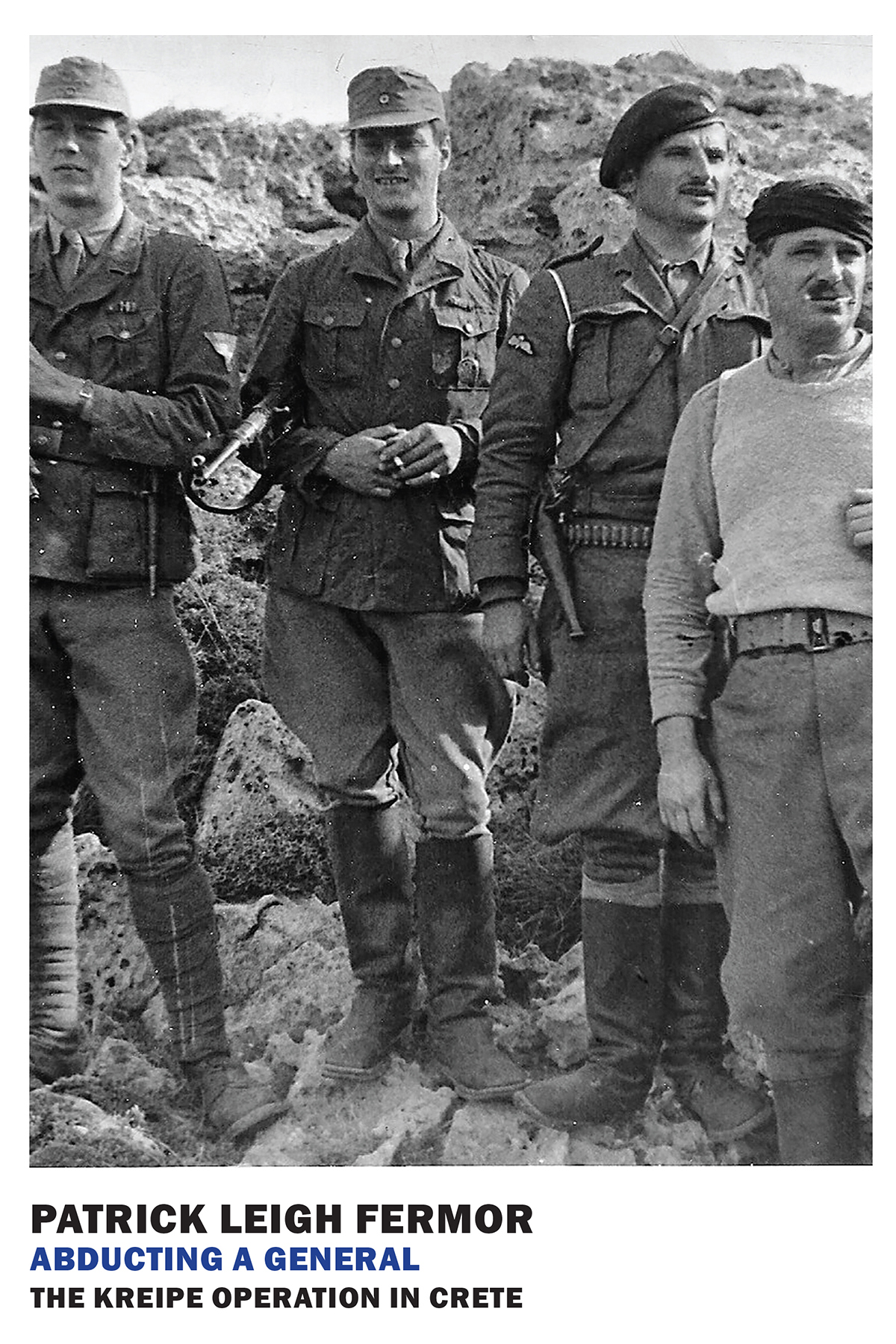

Cover: Members of the abduction team, left to right:

William Stanley Moss, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Manoli Paterakis,

Antoni Paleonidas; photograph The Estate of William Stanley Moss

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fermor, Patrick Leigh.

Abducting a general : the Kreipe Operation and SOE in Crete / by

Patrick Leigh Fermor; introduction by Roderick Bailey.

1 online resource.

Originally published: London : John Murray, 2014.

ISBN 978-1-59017-939-0 () ISBN 978-1-59017-938-3 (alk paper)

1. Kreipe, KarlKidnapping, 1944. 2. World War, 1939-1945

Underground movementsGreeceCrete. 3. Fermor, Patrick Leigh. 4.

Fermor, Patrick LeighTravelGreeceCrete. 5. SoldiersGreat

Britain-Biography. 6. World War, 19391945Secret serviceGreat

Britain. 7. Great Britain. Special Operations Executive. I. Title.

D766.7.C7

940.54'8641094959dc23

2015028467

ISBN 978-1-59017-939-0

v1.0

For a complete list of titles published by New York Review Books, visit www.nyrb.com or write to: Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

Contents

Maps

Foreword

Knossos, the largest archaeological site on the Mediterranean island of Crete, was the mythical home of King Minos. It was also home, it is said, to the Labyrinth, the maze-like structure that held the Minotaur. Half man, half bull, this creature, which had been devouring a regular tribute of Athenian youths, was finally killed by the Greek hero Theseus with the aid of Ariadne, Minos daughter: to help his escape, Ariadne gave Theseus a lifesaving thread to play out during his descent and lead him to safety when the deed was done. Today, a stones throw from Knossos sits a pale-bricked property built in the early 1900s by Sir Arthur Evans, a British archaeologist who had pioneered excavations nearby. Quiet, airy, shadowed by trees and shrubs, the house had been Evanss home. It is still called the Villa Ariadne.

In the spring of 1944, at the height of the Second World War, with Evans long gone and Crete under German occupation, the Villa Ariadne was the requisitioned residence of the commander of the garrisons principal division. The forty-eight-year-old son of a pastor, Generalmajor Heinrich Kreipe was a career soldier who had served in the German Army since 1914. During the First World War he had fought on the Western Front as well as against the Russians, been wounded and won two Iron Crosses. Between the wars he had risen in rank to lieutenant colonel. In 1940 he had fought in France as commander of the 209th Infantry Regiment. The following year he had led his men to the outskirts of Leningrad and won the Knights Cross, the highest decoration in Nazi Germany for battlefield bravery and leadership. Promotion to general and command of his first infantry division the 79th had come in 1943.

Kreipe had been posted to Crete, to command the Wehrmachts 22nd Airlanding Infantry Division, in early 1944. He had been on the island a matter of weeks when, late one April evening, he left his headquarters in the hillside village of Archanes and, sitting in his chauffeured staff car, began the short, unescorted drive back to Knossos and the Villa Ariadne. A few minutes into the journey, at a lonely junction on the road ahead, red lamps loomed suddenly out of the dark. Kreipes car was waved to a halt. Lit by the headlights, two figures in German uniform approached...

What happened next and the relentless drama of subsequent days was later immortalised on screen in Ill Met By Moonlight, a 1957 war film produced by Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell. The film was based on a book of the same name by William Stanley Moss. []

Moss, twenty-two years old in 1944, had been the junior of the two British officers. A captain in the Coldstream Guards, he had been put ashore on Crete less than a fortnight before. Though hardened by front-line fighting in North Africa, he had never, until that moment, set foot on enemy territory. He knew little of Crete or Cretans. He spoke no Greek. But the skills and experience of Mosss friend and colleague whose role in the film would be taken by the actor Dirk Bogarde were quite different.

This officer, a major in the Intelligence Corps, twenty-nine at the time of the kidnapping, had spent the best part of eighteen months on the island, hiding with the locals, speaking their language, disguising himself as Cretan townsman or shepherd, dedicating himself to intelligence-gathering, sabotage and the preparation of resistance. Attached, like Moss, to Britains Special Operations Executive, a top-secret set-up tasked with causing trouble in enemy territory, he had already been rewarded with an OBE. The name of this young officer was Patrick Leigh Fermor.

The tale that follows this Introduction is Leigh Fermors own account of the abduction of General Kreipe. It is published here, in its entirety, for the first time. When he wrote it, in 19667, Leigh Fermor was already on the path to great acclaim as a writer. A Time of Gifts and Between the Woods and the Water, the classic chronicles of his journeys as a young man traversing pre-war Europe, were still some years away, but in 1950 he had published The Travellers Tree, an award-winning account of his recent travels in the Caribbean, and, three years after that, A Time to Keep Silence, an impression of monasteries and monastic life in England, France and Turkey. Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese appeared in 1958 and Roumeli: Travels in Northern Greece in 1966. A novel, The Violins of Saint-Jacques, was published in 1953.

It may seem strange that a man of Leigh Fermors experience and literary flair should not have written sooner about the kidnap. But he and Moss were friends and seem to have agreed early that the latter who, unlike Leigh Fermor, had kept a diary of the operation should tell the story first. Back in England in early 1945, Leigh Fermor had actually acted on Mosss behalf during an initial search for a publisher (a search that the War Office terminated on security grounds when it emerged that many of Mosss cast of British officers, mentioned by name in his text, were still engaged in behind-the-lines warfare). [likely that Leigh Fermor had no desire to steal his friends thunder; and it may be significant that he finally put pen to paper only after Mosss early death in 1965.