T here are certain people who, without seeking or even wishing to do so, acquire an immense importance in the lives of others they touch. They are the men and women who configure new worlds, create landscapes, conjure up horizons or redirect life along unforeseen paths.

Relationships with such individuals are rarely evenly balanced but this need not imply any offence to either party involved. Anyone with the good fortune to have come within their orbit learns how impossible it is to respond to them in an even-handed manner. For these individuals, men and women alike, are walking treasures. Their personalities emanate a rich charisma that extends well beyond what might normally be expected. Or else they exercise the kind of influence on their circle that well exceeds that of any ordinary artist.

Patrick Leigh Fermor was one such individual.

I knew him when he was already well advanced in years. He could scarcely see and had considerable difficulty in hearing. Without a doubt, my appearance was little more than a fleeting and hazy shadow at the end of his days. In contrast, the mark he himself left was profound and enduring.

What follows is an unabashed homage. A homage to the adventurer and author, to the gentleman and jovial host, and to the intrepid warrior. The person who knew how to transform himself into an invincible elderly man, proud and adorable, while retaining every one of the aforementioned attributes.

This text lays no claim to be exhaustive or biographical. It is merely intended as an affectionate portrait: a sketch inspired by informal chats, dinners, whole evenings and an impressive quantity of wine drunk together. Most of all, it is intended to evoke my stays at the home of this author in the weeks before his death.

Readers who are as yet unaware of the life of Leigh Fermor would do well to consult the biographical appendix before starting to read this book from the beginning. They will then enjoy the ensuing pages all the more, having once familiarised themselves with the brief account of the his adventures.

It will come as no surprise that Sir Patrick Leigh Fermor is almost invariably referred to with the simple familiarity inherent in the nickname Paddy. That was the name his friends and acquaintances knew him by, as did indeed the literary media. In Greece he was more usually known as o Mihalis, but thereby hangs another tale

(Kardamili)

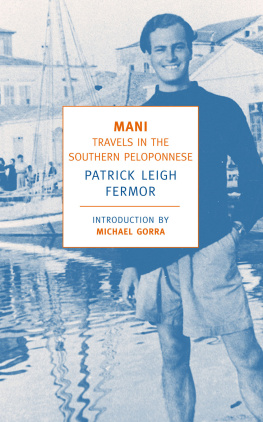

Cooled in summer by the breeze from the gulf, the great screen of the Taygetus shuts out intruding winds from the north and the east; no tramontana can reach it. It is like those Elysian confines of the world where Homer says that life is easiest for men; where no snow falls, no strong winds blow nor rain comes down, but the melodious west wind blows for ever from the sea to bring coolness to those who live there. I was very much tempted to become one of them

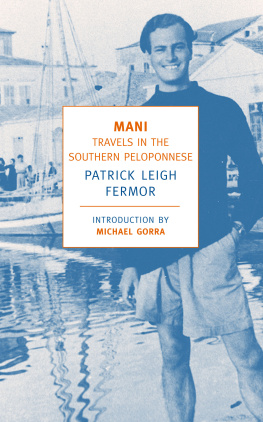

MANI

T he route to Kardamili is a treacherous one. Very deceptive as Paddy used to say, working hard to pinpoint the right adjective, which to a Spanish listener possesses a sonority with hints of disappointment (even while this is not its literal meaning a better route might be to get there by venturing along the coast. Instead the reverse turns out to be the case. The road switches back to meet the sky and returns deep into the labyrinthine mountains once more. It twists and turns, so much so that one can all too easily become lost in a mass of precipices, under the misleading impression you are continually going in the wrong direction, all the time increasingly convinced that you are penetrating further into the inhospitable hearts of the Taygetus mountain range, rather than heading down to the gentle shores of the sea at Messenia. It makes no difference how often you have made the journey, every time you are bound to worry whether you are on the wrong track. It is a feeling that persists for the best part of an hour. But if you resist the temptation to perform an about turn and retrace every step thus far taken, reward finally arrives. Finally, after a terrifying bend that takes one along the edge of a vertiginous precipice, the horizon opens and the coastline of Mani appears, where the enchanting village of Kardamili nestles at the foot of the mountains.

To Spanish translators, the noun decepcin is a false friend: it sounds like deception but means disappointment.

Today the journey is considerably less hazardous. The motorway between Athens and Kalamata has now been completed.

(Of gallantry and grace)

I wouldnt in the least object to having another glass. Would you be so kind, darling?

He would hold out the glass awaiting a refill, and the ice cubes in it jingled. Elpida had hidden away behind the living room door, from where she would issue half-concealed and conspiratorial gestures. Despite her silent and desperate messages, the situation was hopeless. Paddys glass had to be filled up again. Try to drink slowly, that way you can postpone pouring the second or third glass The doctor says you need to serve him smaller quantities. The problem was that whenever Paddy held out his glass for topping up, the only possible option was to obey. Nor was there any chance to substitute good for gold, of replacing full measures of whisky or gin, or vodka, for he drank all kinds of spirits with extra tonic or soda water. Paddy would notice immediately, and just as immediately demand rectification. He became irritated, for he couldnt stand to be treated with condescension. Here, as in so many other instances, Paddy remained invincible. Beneath the outward appearance of a fragile, elderly and amiable old man there persisted a will of iron. No counsel and no warning succeeded in getting him to alter his lifestyle by one iota. And, given that he had survived ninety-six boisterously merry years in this style, one has to conclude that he had right on his side, rather than all those who strive to increase life expectancy by making it boring. (Now Paddy is departed the years do indeed appear all the more tedious).

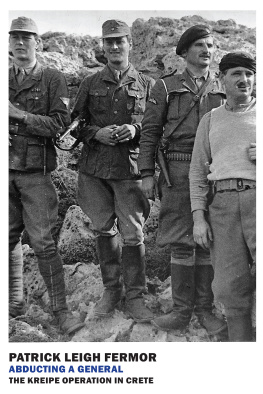

Many opinions were advanced concerning his supposed fortitude or its opposite. Most people regarded him rather as one might an oak tree; his longevity alone inevitably fed such a perception. Those who had known him longer, sometimes over decades, added that he had never really been all that strong. Even as a young man, Paddy had suffered several major ailments, and he had fallen fell seriously ill during the war. In fact his doctors at the Military Hospital where he spent a number of months were on the point of giving him up as a hopeless case. Mention was made of polio, then of various types of rheumatic fever, possibly precipitated by the harsh conditions he had undergone during his time as an SOE officer working with the Cretan Resistance movement: long night marches, extreme cold, living in caves dripping with humidity, where he had slept little and eaten less. Not only did he survive, but he stubbornly manoeuvred to get himself sent back behind enemy lines, back into his beloved Crete my refuge where the Minotaur roars and where he resumed living as unhealthily as before. He was a heavy smoker until the age of fifty, and a monsoon drinker the term was of his own description until the very last night of his life. He ate with relish, and there was little that reached his table that could have qualified as a light meal. He defied every medical statistic in the same way as he ignored every medical opinion, although a fair few had been brought to assist in a diagnosis. With reference to alcohol, it was utterly impossible to throw him off its scent. He could scarcely see, yet he retained an eagle eye for seeking out bottles. If the wine jug used at meal times vanished from its place on the table cloth, or its level dropped more than he reckoned it should, Paddy noticed immediately and, in tones of polite authority, demanded the provision of replenishments.