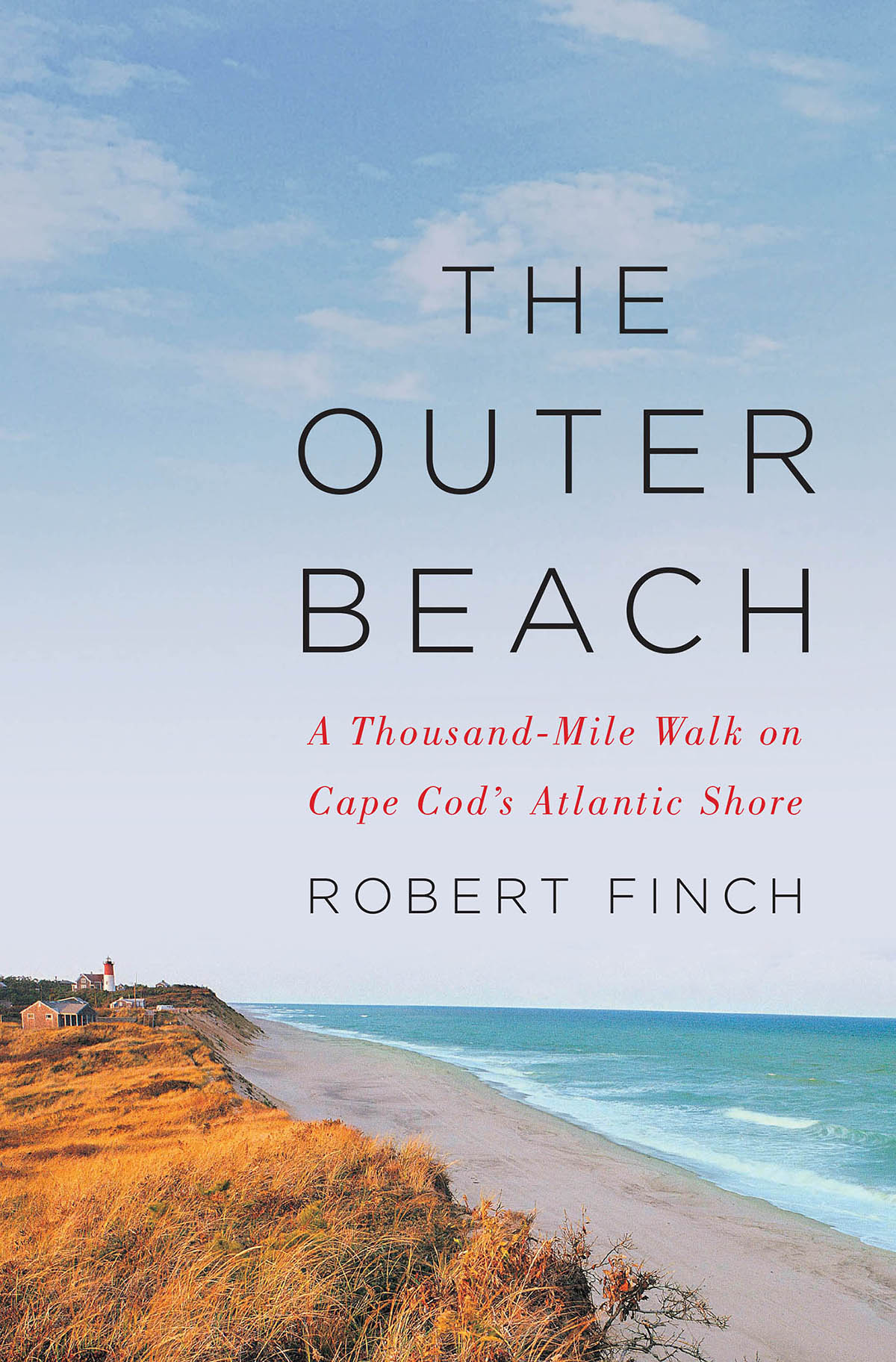

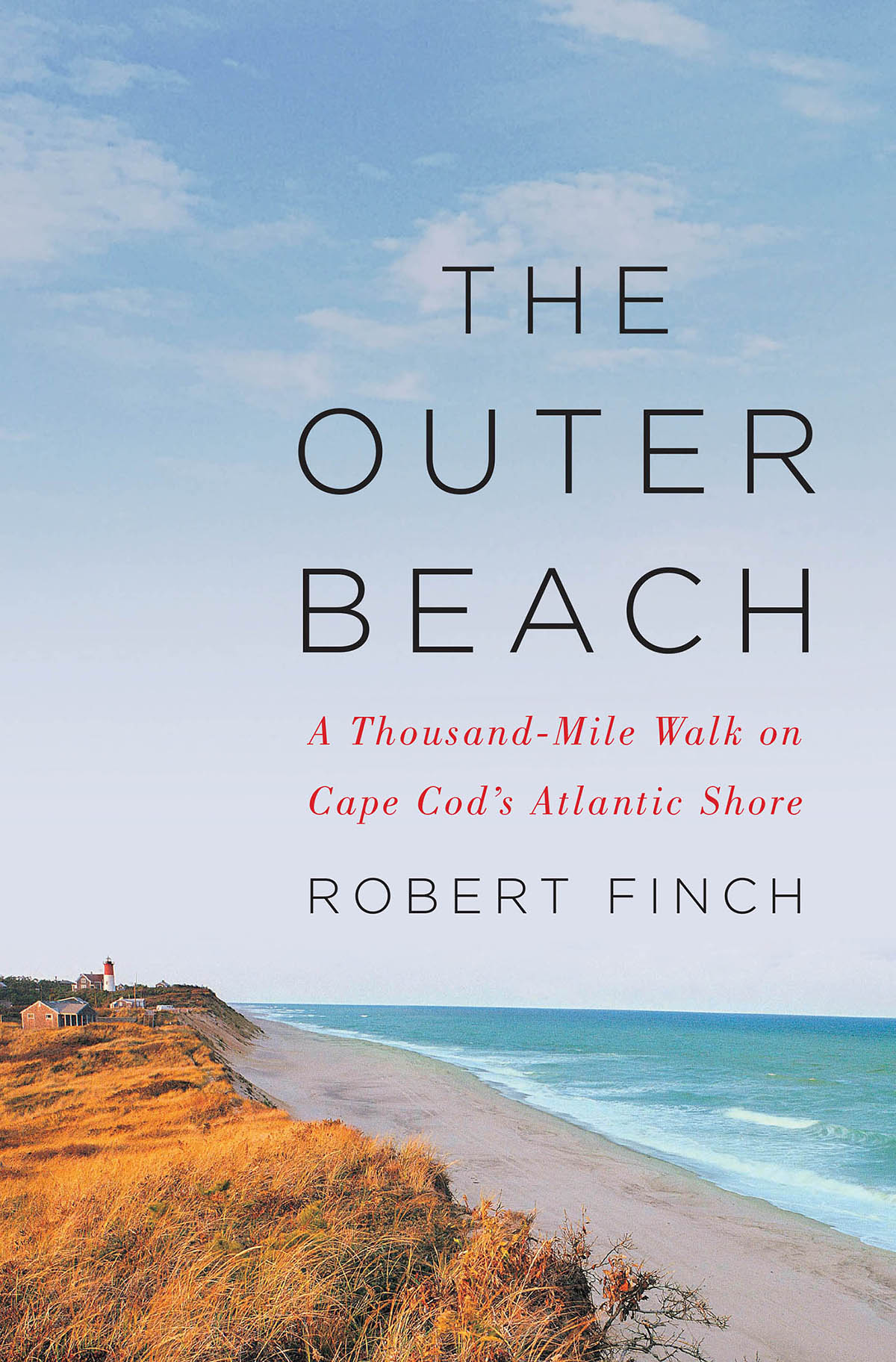

The

Outer

Beach

A THOUSAND-MILE WALK

ON CAPE CODS ATLANTIC SHORE

ROBERT FINCH

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

NEW YORK | LONDON

Copyright 2017 by Robert Finch

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Chris Welch Design

Production manager: Julia Druskin

JACKET DESIGN: CHIN-YEE LAI

JACKET PHOTOGRAPH: (BEACH) STOCKBYTE / GETTY IMAGES; (SKY) ALAN WATKINS / EYEEM /

GETTY IMAGES

ISBN: 978-0-393-08130-5

ISBN: 978-1-324-00052-5 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

In memory of Jim Mairs (19392016),

dear friend and steadfast editor for four decades

The author would like to thank these publishers for their kind permission to republish the following essays:

Night in a Dune Shack and After the Storm from Common Ground: A Naturalists Cape Cod, by Robert Finch. Copyright 1981 by Robert Finch. Reprinted by permission of W. W. Norton.

The Sands of Monomoy and North Beach Journal from Outlands: Journeys to the Outer Edges of Cape Cod, by Robert Finch. Copyright 1986 by Robert Finch. Reprinted by permission of David R. Godine, Publisher.

Barren Ground, Dancing with Lights, Long Nook, Off Hours, and Ghost Music on the Dunes from Death of a Hornet and Other Cape Cod Essays, by Robert Finch. Copyright 2000 by Robert Finch. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint.

In addition, I would like to acknowledge my debt to the many previous books written about the Outer Beach, but especially these four: Cape Cod (1865) by Henry David Thoreau, The Outermost House (1928) by Henry Beston, The House on Nauset Marsh (1955) by Dr. Wyman Richardson, and The Great Beach (1963) by John Hay. They were my constant companions.

Finally, I am grateful to the many friends and family members, implied and overt, who accompanied me on the beach, but especially to Ralph MacKenzie, who makes everything more interesting.

ALSO BY ROBERT FINCH

A Cape Cod Notebook 2

A Cape Cod Notebook

The Iambics of Newfoundland: Notes from an Unknown Shore

Special Places on Cape Cod and the Islands

Death of a Hornet and Other Cape Cod Essays

Outlands: Journey to the Outer Edges of Cape Cod

Cape Cod: Its Natural and Cultural History

The Primal Place

Common Ground: A Naturalists Cape Cod

COAUTHORED AND EDITED BOOKS

The Smithsonian Guides to Natural America: Southern

New England: Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island

(coauthored with Jonathan Wallen)

A Place Apart: A Cape Cod Reader

The Cape Itself

(with photographs by Ralph MacKenzie)

The Norton Book of Nature Writing

(coedited with John Elder)

And landscape, that vast still life, invites description, not narrative.

It is lyric. It has no story: it is the beloved, and asks only to be

contemplated. For contemplation is, in poetic form, love.

This lyric response to the world tends toward rhapsody.

PATRICIA HAMPL, SPILLVILLE

Description is always bad.

JOHN KEATS, LETTERS

LEnvoi:

The Rain of Time

T he other day I was reading yet another article about yet another threat to the future of Cape Cod: water pollution, disappearing wildlife, clogged highways, rising sea levelsI forget what else. Whenever I find myself thinking too much about the fate of the Cape and feel a case of cosmic jitters coming on, I know its time to get to the Outer Beach, preferably during a northeast storm. There I can watch the foundations of this land being eaten out from under me. There I can recover what the local historian Henry Kittredge called the Cape Codders true perspective, where the ocean, the final arbiter of the Capes future, speaks without ambiguity or riddles.

Whenever I do this, Im usually joined by dozens of fellow storm watchers. As they watch the land disappearing beneath their feet, the expression on their faces is not anxiety or dread, but fascination, enjoyment, even exhilaration. During the Great Blizzard of February 1978 I was one of hundreds of people gathered at Coast Guard Beach to watch huge swells pound in the walls of the National Seashores bathhouse and break up the six-hundred-car parking lot that once occupied the now-empty dunes. We cheered at each wave.

Every year some fifty-five acres, or 880,000 cubic yards of precious Cape Cod earth, slide into the sea, and what do we do about it? Where is our communal outrage? After the break in Chathams North Beach occurred in 1987, a dozen houses on the mainland fell into the sea and owners sued town officials for not letting them build seawalls.

When I served on the Brewster Conservation Commission in the 1970s and 1980s, I noticed an interesting phenomenon. Most shorefront owners who sought to build their houses near the beach or to erect protective seawalls would usually accept our Orders of Conditions if they seemed to guarantee the owners at least fifty years of use before the ocean claimed their houses. In other words, peoples concerns about the longevity of their dwellings, and of the land beneath them, seemed to go no further than their anticipated individual lifetimes. This was the case no matter what the value of the property was. Were not so attached to permanence as we sometimes think.

Even without the potential increase in sea level from global warming, geologists estimate that all of Cape Cod will be gone in six thousand years or so, give or take a millennium. (Granted, this is considerably more than Nantuckets estimated remaining time of eight hundred years, which is a shorter term than that of the British monarchy. Better make those ferry reservations now, folks!)

But think of it: Six thousand years before the Cape is utterly gone! Sixty centuriesthe wheel has been around longer than that. And whos protesting? Whos taking the ocean to court to save the Cape? We make such a mighty fuss, as if it matters, even to us. We are spindrift, and we know it.

If this sandy peninsula, thrust so presumptuously out into the ocean, has taught me anything, its been how to live with change and loss, how to face whatever winds blow. Each day the sea takes a little here, adds a little there. Each day the Cape is saved and lost, lost and saved. The ultimate outcome isnt in doubt. On any shore the waves whisper or shout it to us an average of 14,400 times a day. Whose fault is it if we dont listen?

Cape Cod is a cherished face, deteriorating in the rain of time. Like drops of water on a hot stove, we roll around madly on its skin, trying to escape the inevitable. In the meantime, within its shrinking boundaries, everything else is up to us.

Majestic and mutilated, the great glacial scarp of Cape Cods Outer Beach rises from the open Atlantic, separating it from Cape Cod Bay. Its many-colored sands and clays flow grain by grain, or in sudden shelving slabs, to replenish the shore below. The beach itself, broad and gently sloping in summer, short and steep in winter, arcs northward for more than thirty miles, giving the walker a curved prospect two or three miles ahead at most. And always, coming onto the shore and reforming it, with measured cadences in calm weather, with life-destroying fury during northeast gales, is the sea. Here, as Henry Beston put it, the ocean encounters the last defiant bulwark of two worlds. There is no other landscape like it anywhere.

Next page