The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

TO

MISS MABEL DAVISON

AND

MISS MARY CABOT WHEELWRIGHT

INTRODUCTION

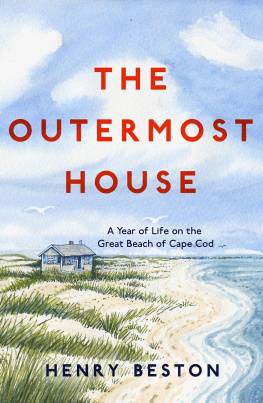

Majestic and mutilated, the great glacial scarp of Cape Cods outer beach rises from the open Atlantic, separating it from Cape Cod Bay. Its many-colored sands and clays flow grain by grain, or in sudden shelving slabs, to replenish the shore below. The beach itself, broad and gently sloping in summer, short and steep in winter, arcs northward for over twenty miles, giving the walker a curved prospect two or three miles ahead at most. And always, coming onto the shore and re-forming it, with measured cadences in calm weather, with life-destroying fury during northeast gales, is the sea. Here, as Henry Beston put it, the ocean encounters the last defiant bulwark of two worlds. There is no other landscape like it anywhere.

This stretch of shoreline has been a remarkably fertile landfall for American nature writing. William Bradford, in his Of Plymouth Plantation, made it the subject of one of the first memorable evocations of the North American coast, that wild and savage hue which greeted the little band of English Puritan emigrs after their rough crossing of the Atlantic during the fall of 1620. Over the centuries an extraordinary number of essayists, poets, and novelists have written of its suggestive landscape. Few, if any, natural areas of comparable size on the continent have been written about so extensively and so well, perhaps in part because this meeting place of land and seaof the gentle, human-scaled contours of the Capes soft sands and the protean, formless wilderness of the open oceanallows us to see what we need to see, providing us with the raw materials of personality and voice.

* * *

Henry Beston Sheahan was thirty-six years old when he first came to Coast Guard Beach (or Eastham Beach, as it was called then) in the summer of 1924. Though he had already published five books (including an account of his experiences as a volunteer in World War I and two volumes of fairy tales), he had not yet made a name for himself and was still casting about for his proper subject and style. After the war he had taught for a year at the University of Lyons and wandered about France, soaking up the Gallic culture he loved so much. But like that other American expatriate, William Faulkner, Beston had to return home, or near it, to find his true identity as a writer.

Though born in 1888 in Quincy, Massachusetts, home of the presidential Adamses, and a graduate of Harvard College, Beston was no Yankee. His father was a successful physician of Irish ancestry, his mother a French Catholic. He was raised bilingually and claimed to think in French as easily as English. This linguistic duality seems to have made him, like Conrad, particularly attuned to the cadences and sounds of written language.

As his career developed, Beston seemed to identify more and more with his French half. His first book, A Volunteer Poilu, was published under his given name, Henry Sheahan, but he subsequently adopted Beston as his professional name, after his paternal grandmothers family. He was a natty dresser. There is a picture of him, taken on the outer beach about 1927, which shows a tall, handsome man with classic Gallic features, sporting a clipped mustache, a French beret, and a dark double-breasted suit accented with a puffed white handkerchief. Thoreau took a flute with him to Walden; Beston brought a concertina to the beach.

Thoreaus famous visits to Cape Cod three-quarters of a century earlier had been undertaken with a typically Yankee sense of purpose: Wishing to get a better view than I had yet had of the ocean, which, we are told, covers more than two-thirds of the globe Beston, on the other hand, seems to have been gradually drawn there by the force of an attraction he only slowly came to understand. In 1925 he bought some fifty acres of duneland on the barrier beach two miles south of the Eastham Life Saving Station. He designed and had built for him a two-room cottage which he named the Focastle. The house was small but not particularly Spartan. He intended it solely as a vacation retreat and had no notion whatever of using the house as a dwelling place.

In September of the following year he went to spend two weeks there, but, The fortnight ending, I lingered on, and as the year lengthened into autumn, the beauty and mystery of this earth and outer sea so possessed and held me that I could not go. He seemed to sense that here at last he might find his full expression as a writer, and so he stayed. In December 1926 he inscribed in his journal, in French, this statement of his subject and purpose:

La Nature, voil mon pays.

Loeuvreclbrer, rvler la mystre, la beaut,

et la mystique de la Nature, du Monde Visible.

Attacher ce sentiment mon nom.

(Naturethere is my country.

The workto celebrate, to reveal the mystery,

the beauty, and the rites of Nature, of the

Visible World.

To bind this feeling to my name.)

Despite this dedication of himself as a writer-naturalist (the phrase he used to describe himself), Beston seemed to have no clear idea of producing a book from his year of living on the beach. Not so with his fiance, Elizabeth Coatsworth, herself a writer and a woman with formidable belief in and ambition for Henrys talents. He left the beach in the fall of 1927 with several notebooks full of material but no publishable manuscript. When he proposed setting a wedding date, Elizabeth replied, No book, no marriage. The Outermost House was published in the fall of 1928; the Bestons were married the following June.

* * *

The Outermost House produced only modest initial sales, but its readership continued to grow. By 1949 it had gone through eleven printings, and in 1953 a French edition was published under the title Une Maison au Bout du Monde ( A House at the End of the World ). With the emergence of a post-World War II environmental literature, it began to achieve something of a cult status. Rachel Carson said that it was the only book that influenced her writing. In 1960 The Outermost House was cited by federal officials as one of the motivating forces in the creation of the Cape Cod National Seashore. It is now generally acknowledged as one of the classics of American nature writing, and each succeeding generation seems to have discovered anew the books unique attraction.

Though written when Beston was middle-aged, The Outermost House is very much a young mans book, passionate and indulgent, full of a sense of discovery and self-discovery. Ever since Walden, American readers have been infatuated with romances of isolation, with solitary truth-seekers in the wilderness. Thoreau went to the Concord woods, he says, to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life. There is something of the same sense of a quest for essentials and a vivid, tactile experience of life in Bestons explanation of why he decided to stay on the beach:

The world today is sick to its thin blood for lack of elemental things, for fire before the hands, for water welling up from the earth, for air, for the dear earth itself underfoot. The longer I stayed, the more eager was I to know this coast and to share its mysterious and elemental life.