Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2011 by Amy Waters Yarsinske

All rights reserved

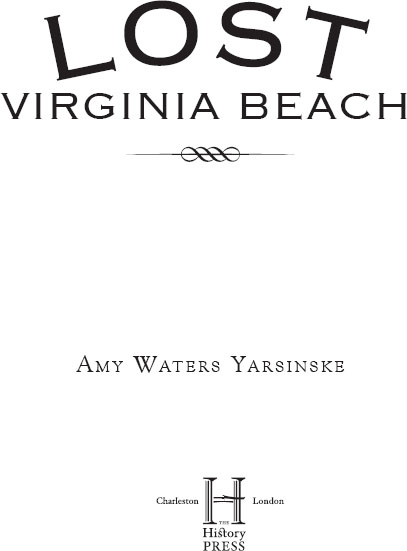

Cover images: Charles Ebbetss July 1932 photographs included several pictures of these Dianas of the Beach taking archery lessons at the Cavalier Beach Club. Courtesy of the author.

First published 2011

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.232.9

Yarsinske, Amy Waters, 1963-

Lost Virginia Beach / Amy Waters Yarsinske.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-60949-204-5

1. Virginia Beach (Va.)--History. 2. Virginia Beach (Va.)--History, Local. I. Title.

F234.V8Y366 2011

975.551--dc22

2011006809

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

INTRODUCTION

The beginning of the end is never quite where we believe it to be. Such is the story of the city of Virginia Beach. Sentimentality aside, from the historic preservation and urban and environmental planning perspective, retaining a sense of place is an important part of establishing community identity. Thusly, Virginias largest populated city and its largest resort destination is a shadow of its former glory. For reasons not always well known nor understood, Virginia Beach has taken inordinately bold steps to bury the character and history that drew permanent residents and visitors to it in large number from the end of World War II. Lost Virginia Beach is the story of what was and will never be again. The pages that follow will take you back to a time when high dunes towered over Cape Henrys beach and eclipsed Long Creek and Broad Bay as sand threatened to close navigable waterways and choke the pine forests below.

Herein you will get a look at the architecture of the Oceanfront, from graciously appointed hotels to cottages, and at the people who lived there and what their lives were like before mid-century modern architecture and dramatic social and economic change swept away a genteel way of life that would never return. You will also be shown what pastoral and beautiful Princess Anne County was like before the land was swallowed up by residential and commercial development, largely unchecked, after the countys 1963 merger with the tiny city of Virginia Beach. But as was opined in the opening line of this volume, the beginning of the end started during a period that does not readily come to mind.

Surely, by the middle of the twentieth century, it was widely acknowledged that both Princess Anne County and Virginia Beach had not done enough to maintain a connection to their respective histories, some going so far as to suggest to county and town leadership that they not be swayed so readily to change place names and that, given the pressure to develop large land tracts, they spare irreplaceable old homes and preserve the cottages and storefronts that lent so much character to the Oceanfront. But stark reality stared back at those who cried preservation; many of the countys prize estates and old places were already gone, erased from the landscape and replaced by new neighborhoods and strip malls. But at Virginia Beach, it was a different story altogether. The tide of development that swept over the beach had begun not just then but rather after the Civil War, when acres of oceanfront land could be bought for as little as twenty-five cents per acre. Development in the name of progress would soon take hold from Cape Henry to the North End.

By the end of World War II, progress had won altogether. Tens of thousands of soldiers, sailors and airmen came home to the United States from duty overseas; many of them had already become familiar with Virginia Beach as a place where they had done a tour of duty, while others recalled it as a place to go on vacation leave. Still others remembered prewar Virginia Beach. Town and county leaders, anticipating the postwar business boon, agreed to pool municipal funding. Close to $2 million was spent to improve and construct a better resort for all of those seasonal interlopers. Mid-century modern hotels and motels were planned and built. The Oceanfront began to take on a very different appearance.

Less than a decade after wars end, in 1952, the resort town of Virginia Beach was designated a city. But Virginia Beachs small-town status would not last long. A little over a decade later, small city and big county merged, an action born largely out of self-preservation. In the years leading up to the 1963 merger, Princess Anne County had lost much of its western border to the city of Norfolk, which started an aggressive annexation campaign after it adjoined all of the northern part of Norfolk County. The merger of Virginia Beach and Princess Anne County thus prevented the city of Norfolk from annexing more of, if not all of, the county, which it expressly sought to do, almost up to the day the merger was announced.

By the end of the 1970s, Virginia Beach was adding one thousand new neighbors per month. More people came at a high price. To clear the way for neighborhood sprawl, high-rise hotels and shopping centers, the wrecking ball was hard at work. Treasured landmarks and old homesteads were razed at an alarming rate. Historic preservationists and historians alike wrote postscripts for prized plantation houses and what remained of old places like Fairfield, the Princess Anne County ancestral home of Anthony Walke, located in modern-day Kempsville.

Look closely at the small pile of bricks, wrote Helen Crist in June 1972, as it was all that was left of the once vast Fairfield plantation. Perhaps it will serve, she continued, as a reminder to those interested in preserving historical homes and areas here, that action is necessary to prevent total destruction of our heritage.

Gone, too, by the end of the twentieth century were places that many of you will remember fondly: the Dome; the Peppermint Beach Club, which held the distinction of being the last shingle-style building at the beach; and the Avamere, Halifax and Sea Escape hotels. As journalist Mary Reid Barrow observed in April 1995, Very little is left along the Oceanfront that even hints of times gone by in Virginia Beach.

AT THE TOP OF THE DUNES

Antarctic explorer and National Geographic editor John Oliver La Gorce called it a war of eternity. He was correct. Observant of remarkable geologic change to the coastline of the United States from the Virginia Capes to the Rio Grande in the fall of 1915, he opined that there was perpetual warfare between the land and sea, with the wind as a shifting ally. Here the land is taking the offensive, he wrote, driving the sea back foot by foot, always with the aid of the wind; there the sea assumes the offensive and eats its way landward slowly and laboriously, but none the less successfully. La Gorce called Cape Henrys smiling sands one of the most interesting points along the south Atlantic coast, a place to study the battle royal between the sea, the wind and the sand. Cape Henry had it all, he observed, the weird beauty of its storm-buffeted beach, extending in broken masses of sand as far as the eye can reach, picked out here and there along the land edge by gnarled and stunted trees, beach grass and hardy shrubs, all of which put up what he called a brave fight against the rhythm of the sea and sand.