Shepard and Smithsimon remind us of the critical importance of public space, not as something given, but as something imagined, contested, and creatively utilized. The Beach Beneath the Streets is inspiring.

Stephen Duncombe, author of Dream: Re-imagining Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy

Skeleton versus bodies, cemeteries against joy; Shepard and Smithsimon create a montage that underlines the weight against which cultural activists push to create a space for all to live in the City of New York.

Marc Herbst, Journal of Aesthetics and Protest

Shepard and Smithsimon have written an especially timely and important book. At a time when all of the public sphere and collectivity is imperiled they have developed an incisive narrative about contestation and resistance. They remind us through both theory and rich case study that the struggle over who controls informal public space is one of the most important front lines in waging a counter offensive to the present blitzkrieg on public services and unions. I highly recommend this book.

Michael Fabricant, Executive Officer, Hunter/CUNY Graduate Center Social Welfare PhD Program, PSC-CUNY

The Beach Beneath the Streets moves like dancers at some illicit street party, right in tune with the rhythms of public life and public space. And like the dancers, bicyclists, gardeners, and activists they describe, Shepard and Smithsimon well understand that this public space remains a contested realm, a place of both repression and resistance, and so a place where essential matters of social life are always at issue. Because of this, and because of its evocative mash-up of images, ideas, and events, Shepard and Smithsimon's book does indeed succeed in prying up the heavy pavement laid down by the powers that be, and in finding beneath it a wide-open world of human possibility.

Jeff Ferrell, author of Tearing Down the Streets: Adventures in Urban Anarchy

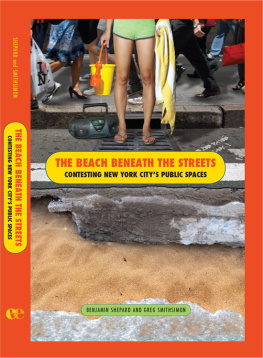

The Beach Beneath the Streets

Contesting New York City's Public Spaces

Benjamin Shepard

and

Gregory Smithsimon

Cover illustration courtesy of Caroline Shepard, www.carolineshepard.com

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2011 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production by Kelli W. LeRoux

Marketing by Michael Campochiaro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shepard, Benjamin.

The beach beneath the streets : contesting New York City's public spaces / Benjamin Shepard and Gregory Smithsimon.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-3619-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4384-3620-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. City planningNew York (State)New York. 2. Public spacesNew York (State)New York. 3. PlazasNew York (State)New York. I. Smithsimon, Gregory. II. Title.

HT168.N5S54 2011

307.1'21609747dc22

2010032059

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Acknowledgments

The name for this book was hatched in one of New York's great public spaces, Prospect Park in Brooklyn, during birthday party of Scarlett, Ben's younger daughter. In much of the United States, public birthday parties are unusual, but New York's small apartments and big parks mean that a sunny day can find three or four kids' parties going on in sight of each other. Kids were hula hooping and chasing each other with squirt guns. The two of us were taking a break from the action, standing in the shade of a tree and talking to another parent when we hit upon the title of the book. That moment captures the many debts we owe: to our families, to the intellectual fecundity of New York's public spaces, and to the many people who provided interviews, insight, inspiration, and action that made this book possible.

Much of The Beach Beneath the Streets was born of conversations during play dates, in New York's parks and streets, its art galleries and restaurantswith our kids, Dodi and Scarlett, Eamon and Una. It is their creative energy and our need to find abundant space for them to play and grow in a healthy, imaginative way, which propelled this project from idea to book. Caroline Shepard and Molly Smithsimon, our wives, were there to support the project as we moved from play dates to dinners and ongoing conversations, and occasional struggles just to move forward. Caroline also provided us with early photos of the streets of New York as well as the cover art for this project (www.carolineshepard.com). Other artists, activists from FIERCE and RTS, and photographers, contributed historic images that are just as irreplaceable. The Times Up! archive as well as activist photographers were tremendously generous with their time and photos.

The research on the history of bonus plazas relied on interviews from people who could have felt no compulsion to be as generous as they were. Among the many architects interviewed, the meetings with Richard Roth in an Upper West Side diner stand out as particularly revealing and representative of a classic use of public space: of how a generation of influential New York city builders eschew their offices or homes and set up meetings in bustling diners. There the sound quality is poor, but the energy of New York's street life energizes the interview. Likewise, the help of Philip Schneider, who continues to advocate for better plazas in the offices of the Department of Planning (although he has nominally retired) was invaluable.

Moving to the Hudson River Piers, we would like to thank Kate Crane, Michael Fabricant, Kerwin Kaye, and Bob Kohler for their close readings of . Thanks to Barton Benes for sharing his story and allowing us to republish copies of photos from his 1978 work Pier 48: Letters from My Aunt Evelyn. Several interviewees, including the legendary Bob Kohler, told their stories in some of the final days of their lives. Two interviewees were sent back to jail. And two of the chroniclers of life on the piers, Allan Brub and David Wojnarowicz, died before their time. They are sorely missed.

We could only write this book because earlier writers, theorists, and activists created the questions, stories, and movements of New York's public spaces. Activists welcomed us as participant observers into their meetings, and walked us through their movements. People like Alex Vitale could walk through a crowded event on Broadway, explaining how the activists' perception of police practices had influenced how they planned an event and organized a group. Groups such as RTS, FIERCE, Time's Up! and its Bike Lane Clowns marched, danced, and pedaled across Manhattan's streets to establish our right to the city. They in turn were building on the insights from queer theorists, the generation of 1968, Emma Goldman, and others who helped invent the idea of a pulsing democratic public space by and for the people. Only because they dreamed there could be a beach beneath the streets could we see it for ourselves.

Our respective academic departments, both vital parts of New York's besieged yet still thriving public sphere, the City University of New York, were just as helpful and just as present in public space. The Brooklyn College sociology department, Gregory's home base, has been a model of an academic department engaged in public space, whether playing softball or participating in a road race together in Brooklyn's parks. Their support, intellectual and collegial, has made working on this book a pleasure. The offices of the Department of Human Services at City Tech are surrounded by some of downtown Brooklyn's best public spaces, and have been the starting point from which Ben has investigated New Yorkfrom its activism to its water-front.