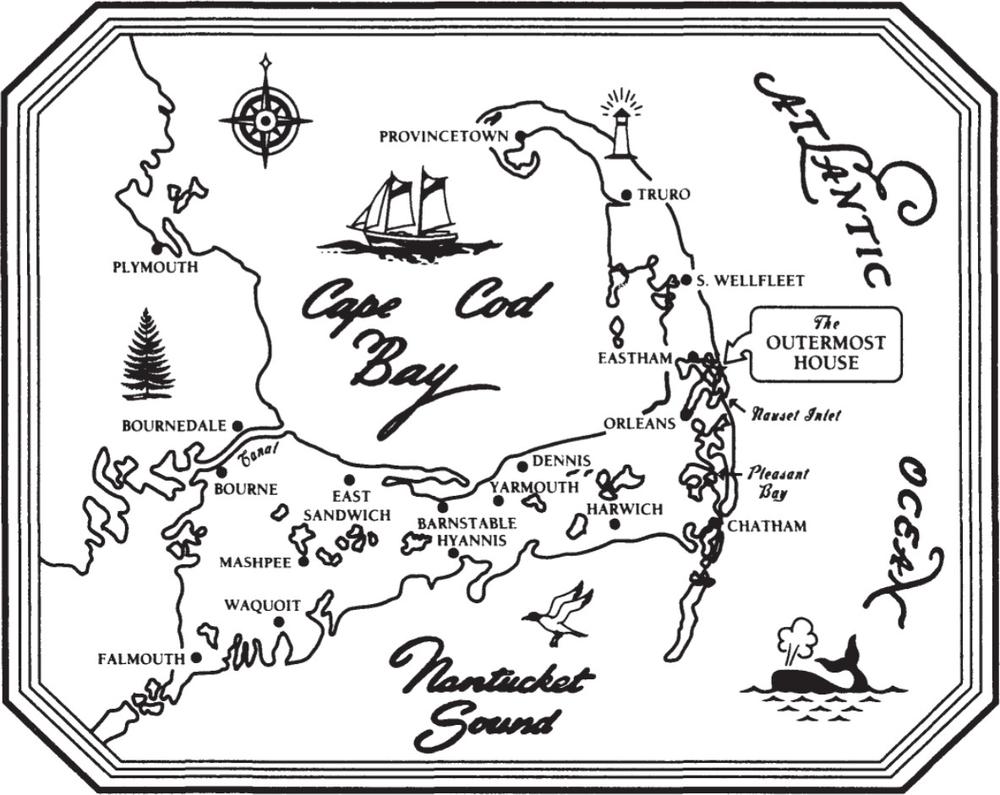

Its a long walk in winter from Nauset Coast Guard Station to the end of the Eastham bar, a sandy spit that echoes the great arm of Cape Cod, held out into the Atlantic from the coast of New England. The sea here is navy blue; the sky the colour of a cormorants eye. Yet as I trudge along the beach with my friend Dennis Minsky, a naturalist and writer, on a freezing January morning, we seem to enter a microclimate. The bitter wind drops and the sun gains strength. The beach starts to seem less bleak. And we dont feel alone. Perhaps its the birds that hover overhead. Or perhaps theres a third person walking with us.

For a few years in the 1920s, Henry Beston knew this place better than anyone else. He endured its winters and luxuriated in its summers, and he observed that this strand was often a few degrees warmer than the rest of the Cape. But it is still stripped back by the cold today, pared to its bones. The beach rises ahead of us, not flat, but rolling like the great waves falling on the shore, fit to pile up more barriers they can break down.

In 1925, Beston bought fifty acres of duneland here, inspired to build what he thought would be a summer house on the site. He called the two-room, twenty by sixteen foot cedar-shingled hut The Focastle, as if it were more ship or ark than house. In September 1926 he went there for two weeksand stayed for a year. The world today is sick to its thin blood for lack of elemental things, for fire before the hands, for water welling from the earth, for air, for the dear earth itself underfoot, he would write. He hoped to reconnect himself here, to know this coast and share its mysterious and elemental life. He left in the late summer of 1927, in the year at high tide, as he called it.

All signs of his tenancy have since been erased by those tides and storms. The dunes themselves have raised and lowered, tethered only by their grasses and shrubs, whose roots, as Beston observed, bind the sand itself, weaving invisibly below the thin crust that forms on the wind-blown sand. Compass grass earns its name, as its dead strands flicker and circle in the breeze, tracing its own radius like a raked Japanese garden.

Strewn above the high water mark are huge pieces of timber, tossed there by the waves; logs that might have floated here from the Gulf of Maine, as Beston recalls, or lumber from ancient shipwrecks, in a sea still echoing with the voices of long-drowned sailors that Marconiwhose early radio station was set on the nearby cliffsbelieved he could record from the ether. At one point in his book, Beston reports an entire ship revealed in the sand, a Mary Celeste sailing out of the dunes. The sea spits it all out. In the local museum at the Highland Light, up the shore at Truro, a row of assorted chairs salvaged from different wrecks stand against the wall, as if waiting for their owners to resume their seats. The Cape has always been a haunted place.

Life is hardscrabble. The tracks of horned larks run side by side with coyote paw prints. Half buried in the dead tufts of turf are the carcasses of eiders and herring gulls; the beach as cemetery. Close to where Bestons hut stood is something truly strange: a desiccated, primeval sturgeon, all grey spines and plates, a prehistoric monster cast up by the sea. It points its bony snout out to the water, waiting to regenerate. We might have been standing here twenty thousand years agoif it werent for the fact that this land didnt exist until then, when the Laurentide ice sheet that formed it began to retreat in the Pleistocene.

Time compresses, speeds up. We scratch about in the sand by the great pooling inlet that floods out from the marsh to the sea, emptied and filled twice a day by the tide, but we cant find any trace of Bestons hut. Dennis saw the last of it, in the great storm of 1978 that finally pulled it apart. It had been successively moved back, in retreat from the rising sea, but the sea would have its bones. Dennis remembers seeing a few scattered planks, the last residue of Bestons investment in this place.

It is a calm enough scene on this winters day. It is hard to even remember that the world beyond this beach exists. Everything seems concentrated to this here, this now. But strangely enough, the violence of the taking of the Focastle seems a mirror of what brought Beston here in the first place. This battlefield of the elements was a kind of sympathetic magic; it drew Beston away from the memory of recent trauma.

* * *

Henry Beston Shearan was born in Quincy, Massachusetts in 1888. His father was a doctor of Irish descent; his mother, a French Catholic. He was educated at Harvard, but was drawn to Francehis mother died when he was eight years oldand he later studied at the University of Lyon. He was a handsome, broad-chested young manhe looks like an American football player in early photographs. In others he wears a dandified double-breasted suit, complete with beret. In 1915, he joined the French army, and served as an ambulance driver on the Western Front. In the last year of the war he joined the US Navy as a press representative.

In what seems like a strange transition, after the war he would begin writing fairy storiesThe Firelight FairyBook (1919) and The Starlight Wonder Book (1923). But perhaps these were a reaction to his wartime experiences, in the way that the war itself had seen a remarkable rise of belief in faeries, angels and other aspects of the supernatural. In a way, Bestons precise but romantic writing turns the Cape into a kind of fantasy; a retreat into nature and sun worship. Beston found a kind of solace there. He was a man who had returned from the First World War in which hed worked as an ambulance driver, picking up the deadly flotsam and jetsam of an industrial war that had turned the land into an awful perversion of the natural world: the Western Front had become a terrible heaving sea, coursed by tanks, called land ships, patrolled by men in gas masks like aqualungs, and shellholes flooded with fetid water in which they might drown.

Beston saw many men die. At one point he has a conversation with a young soldier on guard duty about how the war is proceeding. Moments after Beston walks away, a shell falls and he watches as the soldier seems to inflate like a balloon, then falls back, imploded. A chunk of the shell had ripped open the left breast to the heart. Down his sleeve, as down a pipe, flowed a hasty drop, drop, drop of blood that mixed with the mire.

Later, Beston is taken even nearer to the front line. No Mans Land had widened to some three hundred feet of waving furze, he wrote, over whose surface gusts of wind passed as over the surface of the sea. About fifty feet from the German trenches was a swathe of barbed wire. Upon this mist hung masses of weather-beaten blue rags whose edges waved in the wind. Des camarades (comrades), said my guide very quietly.

The memory of rotting men caught like crows on a barbed clothes line must have induced elements of what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder in the writer. Beston left that horror behind for this utopian vision, this New Englandonly to find a new place of loss. The shipwrecks he witnessed, the life and death struggle of the beach, the bulwark of the Cape itself; they all seemed to bridge the living and the dead.

The nearest humans to the Focastle are the young surfmen who staff the lifeguard stationmost of them Cape-born. Theyre soldiers of the sand and sea, patrolling the dunes in all weathers: in fog and sun and blinding sandstorms and drifting snow that obscures all landmarks. Beston keeps hot coffee on his hearth should he hear his friends footsteps at any time of night as they call in to see if he is OK. In the bleakest winter, he sees them carrying their lanterns in the desolation, looking out for lost souls. Those lights along the surf have a quality of romance and beauty that is Elizabethan, he says, that is beyond all stain of present time.