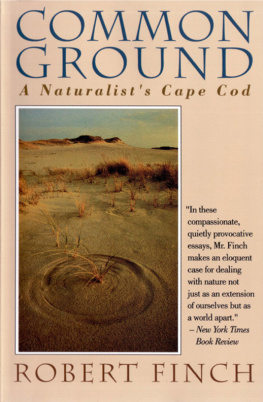

Common Ground

First published in 1981 by

David R. Godine, Publisher, Inc.

First published as a Norton paperback 1994

Copyright 1981 by Robert Finch

Illustrations copyright 1981 by Amanda Cannell

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Finch, Robert, 1913

Common ground, a naturalists Cape Cod.

1. Natural history Massachusetts Cape Cod.

2. Cape Cod. I. Title.

QH106.M4F56 574-974492 80-83953

ISBN: 978-0-393-34843-9 (e-book)

Acknowledgments: The essays in this book are reprinted by permission of The Cape Codder, The Provincetown Advocate, The Register, and the Falmouth Enterprise, in which they first appeared. They are reprinted here in slightly revised form.

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110 W. W. Norton & Company Ltd, 10 Coptic Street, London WC1A 1PU

www.wwnorton.com

To the staff and members of the

Cape Cod Museum of Natural History,

who helped make these journeys possible.

Contents

Common Ground

Foreword

This is a book about beginnings, or landfalls, in a place by the sea that has been explored, settled, visited, studied, and written about more than almost any other stretch of the North American coastline. Yet despite its long history of intense use, Cape Cod is still essentially, as it was to the Mayflower passengers, an unknown coast. For each individual arriving new on its shores, it offers a place to begin, to stumble, to leave and return to, and finally, perhaps, to stay.

In one sense, perhaps the most important, the specific setting of these essays is incidental. In another, of course, the Cape is a very special place, not only because it is famous as a summer playground, or because of its intimate relationship with the ocean (not all towns have whales wash up in their backyards), but for that peculiar figure it has always formed in the American imagination, a figure at once microcosmic and unique, representative and individual. As a friend of mine once said to me regarding television coverage of our local herring run: If it happens on Cape Cod, its more important.

For me the Cape has also been a place of unusual accessibility to the natural world and to all that implies, a landscape whose low hills and long shores seem to answer the contours of my own imagination.

The focus of these essays, then, is personal, one mans response to the changing face of this curved peninsula. Their aim is not primarily natural history, nor am I a naturalist except in the sense that nature is the largest object on my horizon, a fact that has gradually led me to learn something about its basic processes. The essays were written over a period of several years with the intent of exploring the idea that, in a global age, it becomes increasingly important to keep in touch, on a direct and personal level, with the place where one lives. I felt that living with nature in the late twentieth century must mean more than turning down the thermostat and meeting state sanitary codes. There is no code for it; nature is not something to coexist with, but existence itself.

Not only the Cape, but every locale, needs to be measured by the human foot and eye as well as with population graphs and water studies. It needs to be sounded, not merely for its capacity to support human traffic and commerce, but for its seasonal mysteries and secret running life. It needs to be known, not only from soil samples and by planning boards, but in its many moods and expressions, its comings and goings, its various lives and forces that can excite wonder and awe and new ways of seeing. And it needs to be supplied, not just with tourists and oil, but with a love that inspires discipline and commitment from all who use it.

We always undertake more than we know, however, and now these pieces seem to form a record of changes in myself as well, the loose outline of a journey of coming, sometimes flawed, to the natural world. There is also, in the later ones, some attempt to balance human and natural concerns, but only as a beach is in dynamic balance with the ocean that constantly reshapes it.

The road to nature is always a footpath. Whatever environmental ethics one does or does not subscribe to, each individual must come to his or her own terms with the world. Thus most of the explorations in this book were of necessity taken alone.

In another sense, however, no journey is ever taken alone. Besides the help and encouragement received from my family, my friends at the Cape Cod Museum of Natural History, and especially from my editor at Godine, Deanne Smeltzer, this book depends significantly on those who have walked these shores before me: explorers, scientists, historians, artists, the old Cape Codders themselves, and above all, other writers. There are many references to those major voices unusual in number for a place so small who have imagined and articulated this landscape in ways that have forever changed the way we look at it: Thoreau, Henry Beston, John Hay, Conrad Aiken, and others.

Yet just as no one can repeat Thoreaus famous walk along the Outer Beach (the route of which is now more than a hundred yards out to sea), so the past, however compelling, is constantly eroding to some degree. The present always calls for fresh eyes, not just to pierce the mystery anew, but because too often what we think we see is not the Cape itself, but merely the surface, and then a false surface: an oversimplified, stereotyped myth of national nostalgia known as Old Cape Cod.

Too much false seeing and false thinking about such a vulnerable land have already caused serious problems, and will cause more if not corrected. They will also take away those rich resources for individual growth that the true natural variety of any place affords. For whatever changes have occurred, however much has been irrevocably lost of the past and those who lived it here, we are always left with what the First Comers had to begin with: the land itself, sea-born and sea-shaped.

Greatly altered in appearance in places to the point of unrecognizability Cape Cod nonetheless remains as fundamental, challenging and unexhausted a departure point for discovery and self-discovery as it ever was. After more than three and a half centuries of occupation by Western man, the real Cape still eludes us, offering and withdrawing its mysteries with the tides, saying follow me, know me, live with me.

ROBERT FINCH

Brewster, Massachusetts

February 13, 1981

O thers than myself should be writing this. I have been at best an infrequent visitor to the dune country, or what used to be called the outback of the Provincelands. I no longer even live in Provincetown. It would be better done, I suspect, by one of the shack people those enviable individuals who live among the dunes summer after summer, and even year-round, in those marvelous barnacle-boxes still perched here and there along the outermost line of dunes from Race Point to High Head. Many of them have been writers themselves, ever since Eugene ONeill worked on his early plays out there in the old Peaked Hills Bar Life Saving Station. It is they who best know that country, those several square miles of sea-spawned, wind-shaped sandhills and valleys, domes and bowls, that sprawl between Route 6 and the Atlantic Ocean at the very tip of Cape Cod a region once described by Mary Heaton Vorse as a little wild animal that crouches under the hand of man but is never tamed.

Next page