Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

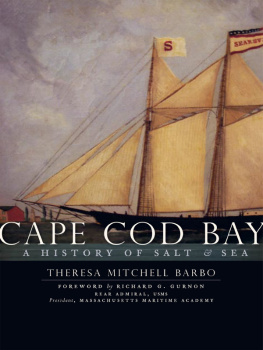

Copyright 2012 by Theresa Mitchell Barbo

All rights reserved

Cover images courtesy of Bill Byrne, Burton Derek, Heather Fone, Cathrine Macourt and Kenneth G. Morton.

First published 2012

e-book edition 2012

ISBN 978.1.61423.554.5

print edition ISBN 978.1.60949.225.0

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Dedicated to

Barbara U. Birdsey

Friend, Mentor and Advocate for Animals

&

Founder,

The Pegasus Foundation

Orenda Wildlife Land Trust

The Cape Wildlife Center

In wildness is the preservation of the world.

Henry David Thoreau, speech at Concord Lyceum, April 23, 1851

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

I love going to Cape Cod. My first visits were family vacations more than fifty years ago. I reveled in playing on the beaches, fishing, eating seafood, trying to identify the mysteries left by the tides and exploring the many secret places hidden in the Capes complex systems of dunes, marshes and woodlands. More recently, most of my visits have been the more responsible, grown-up type: building collaborative programs for environmental research and education. But I treasure those times when work is left behind and I can introduce my children and grandchildren to those same wonders that fascinated me as a child.

The story of Cape Cod is one of change. There are areas that are vastly different than when I was a boy. Much of that, of course, is due to alterations that (for better or worse) our species has madesand plains and Pine Barrens turned into suburban sprawl and shopping malls or otherwise paved with the artificial green of lawns. But by and large, the biggest changes have been due to natural forces.

The colors and textures of the waters vary with season, wind and sun. Each tide alters the look and contours of the beaches. Every storm takes sand away in some areas and deposits it in others. Sand, clay and gravel dont stand up well against the constant battering of the seas. Bigger changes can be appreciated when one reads old histories or looks at old maps. Author Dorothy Sterling talks about Billingsgate Island in Wellfleeta place where farmers once pastured horses but is now just a sandbar at low tides. Almost every Cape Codder knows the story of the vibrant fishing village at Monomoy, which flourished for over one hundred years until the hurricane of 1860 washed away its harbor and the town was abandoned.

My brother the geologist often reminds me how these changes pale beside the changes of geologic time. Before the last advance of the glaciers bulldozed this area over twenty-five thousand years ago, there was no Cape Cod. At the height of the glacial advance, sea level was about four hundred feet lower than it is now. Mastodons, mammoths, horses, camels and other marvelous creatures grazed on grassy and forested plains east of todays beaches. These former plains are now our continental shelf. As the ice melted, sea level rose, again covering these lands. The melting glaciers left behind moraines, huge piles of sand and gravel that had been pushed up in front of them. Some of these piles now have names like Long Island, Marthas Vineyard and Cape Cod. Gradually, these new places were colonized by a wide variety of plants and animals. Elk, caribou and bison grazed in many areas of Massachusetts. By about eleven thousand years ago, Cape Cod probably looked pretty much like it was when the Pilgrims landed.

When the ancestors of todays Native Americans arrived, Cape Cod must have been a near paradise, overflowing with an abundance of natural resources, including game, fish, shellfish and innumerable wild birds. It is difficult for those of us alive today to imagine the abundance of wildlife that faced the first Europeans when they arrived on Cape Cod. But a perusal of the writings of early explorers and naturalists sounds almost unbelievable by todays standards. They talk about being able to go out in fishing boats, dip baskets into the sea and bring them up full of codfish; walking out from the beach and being able to catch lobsters by hand among the seaweed; watching migrating flocks of shorebirds and ducks so large that a single flock might take an hour to fly by. In the spring, alewives, sturgeon, Atlantic salmon and other fish filled coastal creeks and streams as they made their seasonal migrations from the ocean to breed in fresh water. Immense schools of plankton-feeding menhaden were thick in coastal waters, some single schools stretching from Cape Cod to Long Island, New York.

As a fan of science fiction, I often wish that I had access to a time machine. It would be exciting to travel back and view Cape Cod the way it was one thousand years ago, when the Vikings visited the area. Imagine visiting Native American groups like the Wampanoag prior to the colonization of Europeans and observing how they hunted and fished in the area and their extensive farming of corn, beans and squash. How did Cape Cod look to Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524? From a distance, the beaches, forests and plains would have appeared very much like we see them today. There would have been Wampanoag communities near many of the places where todays towns exist. But there would be no Cape Cod Canal and none of the roads, buildings or infrastructure deemed so essential to modern civilization.

What of the context and frame of Theresa Barbos book and reflections and echoes on wildlife and their habitats? What about animals and plants? The last few hundred years have been a mixed story of extinctions, extirpations and introductions of new species through human activities, combined with the arrival of new colonist species that have arrived here through their own agency as habitats and climates change. The wildlife of Cape Cod has altered significantly over the years, and it continues to change today.

Also known as groundhogs, woodchucks (Marmota monax) are mysterious. Although they live on Cape Cod, they arent seen very often. Courtesy of Heather Fone/HSUS.

When the Pilgrims landed, wolves would have roamed the landscape, while one of their favorite prey species, white-tailed deer, would have been less common than today. As wolves were eradicated by colonists, deer numbers probably climbed but then declined again in the 1800s due to overhunting and habitat changes. In 1883, Massachusetts passed a law prohibiting deer hunting on Cape Cod that was rescinded in later years as deer numbers recovered. Coyotes, on the other hand, are new arrivals. They arrived in western Massachusetts in the late 1950s and most likely crossed the bridges onto Cape Cod sometime in the early 1970s.

Europeans brought with them unwelcome stowaways as they came to the New World. Old World rodents, the house mouse and the Norway rat, were early arrivals. These species have had major ecological impacts, including carrying disease to people, domestic animals and wildlife. Weve almost all had experiences with these rodents, but some unwanted invaders are less well known. For example, the common earthworms that we dig up in gardens and use for fishing are introduced, exotic species. These worms were most likely brought from Europe and Asia in the soil accompanying agricultural and ornamental plants. But these introduced worms (about one-third of the worm species in North America) cause dramatic changes in the recycling of important soil nutrients and are of great concern to ecologists, foresters and conservationists. Other invertebrates (most terrestrial and aquatic) have been introduced both accidentally and on purpose. The gypsy moth was brought to Medford, Massachusetts, in 1869 in the hope of starting a domestic silk industry. Unfortunately, some escaped, became established and have spread widely, causing great aesthetic, economic and ecologic damage to trees across Massachusetts, including Cape Cod.

Next page