IMAGES

of America

LIGHTHOUSES

AND LIFE SAVING

ALONG CAPE COD

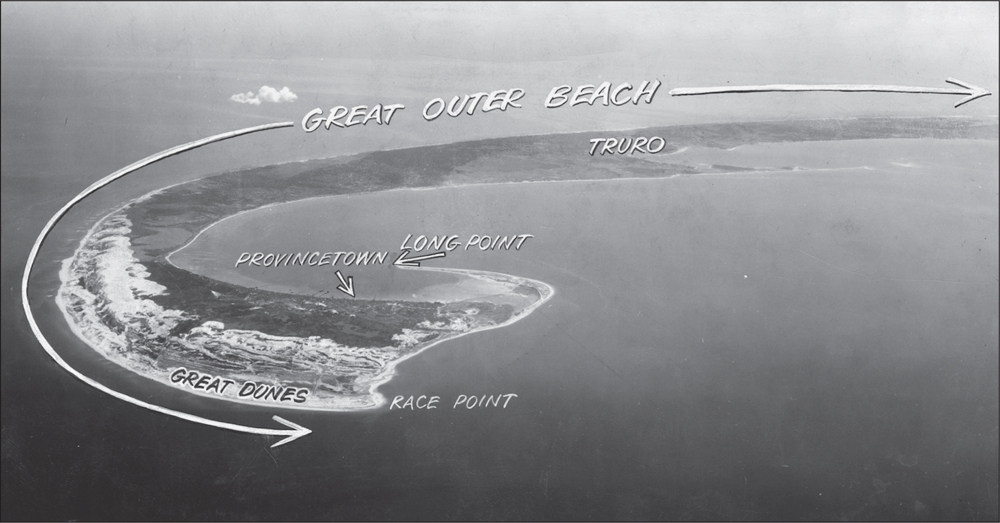

The Great Outer Beach of Cape Cod extends east and south from Race Point in Provincetown to Monomoy Point in Chatham. Beyond the shifting sandy beaches are numerous hidden sandbars. Hundreds of shipwrecks have occurred off these shores over the years, with great loss of life. This c. 1954 photograph shows the area from Provincetown to Wellfleet from 19,200 feet. (Photograph by Institute of Geographical Exploration at Harvard University; authors collection.)

ON THE COVER: A Life-Saving Service crew prepares to launch their surfboat toward a wreck. Cape Cod crews worked in all weather, overcoming all hardships to affect rescues, and over the years, the crews achieved an unprecedented record of lives saved. By the 1890s, the Cape Cod shipping lanes would be guarded by 13 life-saving stations, 21 lighthouses, and 10 lightship stations in an effort to prevent shipping tragedies. (Authors collection.)

IMAGES

of America

LIGHTHOUSES

AND LIFE SAVING

ALONG CAPE COD

James W. Claflin

Copyright 2014 by James W. Claflin

ISBN 978-1-4671-2213-9

Ebook ISBN 9781439646328

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013957854

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To all the men and women of the US Coast Guard who carry on the traditions, and to my father, Kenrick A. Claflin

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Although the majority of the photographs and images used in this volume are from my own collection, I could not have put this book together without the kind and able assistance of a number of individuals.

First, thanks should go especially to my dad, Kenrick A. Claflin, who passed on to me a love and appreciation of history, his integrity, and the love of all things maritime and antique.

Thanks should go to Andy and Anita Price, maritime antique dealers and fine artists, for their friendship, encouragement, and willingness to answer my many questions over the years.

Also thanks to Ralph and Lisa Shanks for their continued encouragement and support over the years; to Frederic L. Thompson, author of The Lightships of Cape Cod; and to lighthouse and Life-Saving Service experts Richard Boonisar and Jeff Shook. Additional thanks to Life-Saving Service small-boat historian Cmdr. Timothy R. Dring of the US Navy Reserve (retired) for his willingness to help whenever I ask and for the use of some of his station photographs.

I also wish to thank my editor at Arcadia Publishing, Caitrin Cunningham, and the Arcadia staff for their guidance on this and other volumes over the years.

My sincere appreciation to you all. You were most kind and generous, and you took the time when I asked. I also would like to express my sincere gratitude to all of the lighthouse keepers, lifesavers, Coast Guard personnel, and their families, both living and past. You all have performed your duty well and set the standard for the future.

And, finally, thanks to Margie.

Unless otherwise noted, all images appear courtesy of the author and Kenrick A. Claflin & Son Lighthouse Antiques.

INTRODUCTION

Arthur W. Tarbell wrote of outer Cape Cod in 1934: From Monomoy Lighthouse in Chatham to Long Point Light at Provincetown... from the elbow of the Cape to the tip of its slender forefinger, this long shore arches out like a huge crescent into the Atlantic.

By 1914, there would be 203 life-saving stations dotting the coastline of the United States, 13 of them on Cape Cod, but in the mid-18th century, there were none. And there were only a handful of lighthouses in the country in the 1770s as well.

New Englanders have always been heavily dependent on the sea for their employment, commerce, and nourishment. By the 1800s, with thousands of vessels plying the dangerous waters of Massachusetts Bay, around Cape Cod, and through Nantucket Sound, the chance of a shipping disaster was always great. Hundreds of shipwrecks did indeed occur off the Massachusetts coast, with startling losses.

During the colonial years, each of the 13 colonies established a handful of lighthouses and other navigational aids according to their needs. The first lighthouse in the colonies was lit in Boston Harbor on Little Brewster Island in 1716. As time went on, the need for more beacons was realized, and additional lights were established on Brant Point on Nantucket in 1746, in Plymouth on Gurnet Point in 1769, and on Thatcher Island off Cape Ann in 1771. By 1792, as traffic around Cape Cod continued to increase, mariners began to petition for a sorely needed lighthouse on Cape Cod.

As commerce increased and shipwrecks and attendant loss of life became more frequent, the newly formed federal government realized that a more coordinated system of lights and navigational aids was needed. Thus, in 1789, Congress acted to place the responsibility for all navigational aids under the federal government. Unfortunately, during this period, economy of operation ruled over efficiency, causing the lighthouses of the United States to become some of the poorest-quality in the world. Many concerns were voiced until the new Light-House Establishment was formed in the 1850s under one administrative board. Thus began a new era, one of high quality and efficiency that continued through the 1930s, when the Coast Guard assumed responsibility.

At about the same time, the citizens of Massachusetts were becoming more concerned about the incidents of shipwreck and loss of life along the coast. Although a coordinated system of lighthouses and lightships helped many a mariner find his way clear of treacherous shoals and sandbars, the occasional shipwreck did inevitably occur as the fog and fierce New England storms forced ships ashore, causing repeated loss of life. Sometimes, shipwrecked sailors were able to make their way ashore only to perish on desolate beaches from lack of shelter. Prominent citizens of the day began to appreciate the need for a system of shelters and rescue for mariners driven ashore, and in 1785, an organization to be called the Massachusetts Humane Society was founded. Many notables of the time, including Paul Revere and John Hancock, were listed on the rosters of the society, and there began what would become the foundation of the American system of rescue from shipwreck. Based on the British model, the Massachusetts Humane Society began to establish huts along the shores to provide shelter to those in need. On Lovells Island in Boston Harbor, the first house of refuge was established, with many more to follow. By 1807, the first lifeboat station would be established by the Massachusetts Humane Society and provided with a first-class, 30-foot whaleboat manned by 10 volunteers. Many rescues were performed using this boat, and the die was cast. By the 1870s, the Massachusetts system had grown to over 70 stations. But just as with the lighthouses, a still-more efficient and coordinated system was needed as maritime trade continued to expand.

After a number of spectacular shipwrecks and fatalities, Congress finally in 1871 appropriated funds to create a coordinated system of life saving along the coast, and by the late 1870s, Sumner Increase Kimball would take over as its superintendent. The service became the US Life-Saving Service, and by the next decade, Kimball had created a model service that would last for 45 years and would boast an unprecedented record of rescues, service, and organization.

Next page