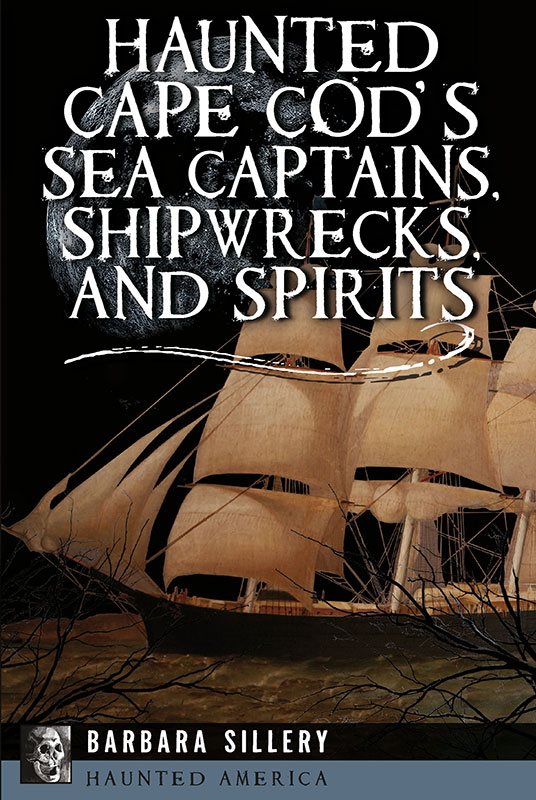

Other Pelican Titles by Barbara Sillery

The Haunting of Cape Cod and the Islands

Haunted Cape Cod

The Haunting of Louisiana

Haunted Louisiana

The Haunting of Mississippi

Copyright 2022

By Barbara Sillery

All rights reserved

The word Pelican and the depiction of a pelican are trademarks of Arcadia Publishing Company Inc. and are registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

ISBN 9781455626823

Ebook ISBN 9781455626830

Photographs by Barbara Sillery unless otherwise indicated

Printed in the United States of America

Published by Pelican Publishing

New Orleans, LA

www.pelicanpub.com

To Glinda Schafer, an extraordinary artist and an extraordinary friend. Thank you for all the years of being there for me.

Contents

An anonymous sea captains wife at the Colonial House Inn in Yarmouth Port.

Prologue

There are three sorts of people; those who are alive, those who are dead, and those who are at sea.

Old Capstan Chantey, attributed to Anacharsis, sixth century BC

Cape Cod juts out into the Atlantican arm with clenched fist, daring all who challenge her rugged coast ringed by treacherous shoals. Ancient mariners to and from this island haven have been explorers, conquerors, merchants... and pirates. On Cape Cod, these menand womenhave ventured forth to put food on the table, bring back exotic goods for trade, hunt whales, and return home to revel in this mysterious and magical place where souls of the dead linger on.

Clipper ships, packet ships, whale boats, and steamers left home ports on Cape Cod to navigate through perfect storm, after storm, after storm. There was a price to payships foundered in the gales, resulting in a high death rate for crews and passengers. Given the length of the whaling voyages, averaging two to three years, sea captains were often accompanied by their wives and children. Capt. Caleb Hamblins son Sylvanus was born at sea to his wife, Emily, in 1869 while on board the whaler Eliza Adams. Other infants did not make it to celebrate their first year.

The spirits of those who survived and settled back as landlubbers on their beloved Cape Cod refuse to leave. They have tales to tell, adventures to share, and a certain stubbornness that will not be dispelled. A belief in the afterlife is not required to enjoy their stories.

Lagniappe: Each of the chapters ends with lagniappe (lan yap), a Creole term for a little something extra. When a customer makes a purchase, the merchant often includes a small gift. The tradition dates back to the seventeenth century in France. When weighing the grain, the shop keeper would add a few extra kernels pour la nappe (for the cloth), as some of the grains tended to stick to the fibers of the material. In New Orleans, where I lived for more than three decades, lagniappe is an accepted daily practice. It is a form of good will, like the thirteenth rose in a bouquet of a dozen long-stemmed roses. The lagniappe at the end of each chapter offers additional background on the ghost or haunted siteperhaps just enough more to entice you to visit these Cape Cod locales and seek your own conclusions. Addresses for these haunted sites can be found at the end of this book; contacting the ghosts is up to you.

Message in a Bottle

On board the Pacific, from Lpool to N. York. Ship going down... confusion on board. Icebergs around us on every side. I know I cannot escape....

Wm. Graham

In 1861, a waterlogged message in a bottle found adrift near the Hebrides, an archipelago off the west coast of Scotland, was reputed to be the only vestige left of the Pacific, a luxury oceangoing steamer. Investigation into the ships manifest revealed crewmember Robert Graham as the likely note writer resigned to his fate.

On January 25, 1856, Aza Eldridge, a legendary sea captain from Yarmouth Port on Cape Cod, set sail from Liverpool, England to New York. Ships sailing before him reported large icefields in the North Atlantic. The seas were brutal. When Eldridges ship, the Pacific, failed to appear at her final destination, it was generally concluded shed sunk after colliding with a large mass of ice.

The Pacific vanished with all aboard. Forty-five passengers and 141 crew, including Captain Eldridge, were never heard from againexcept for the one desperate scribbled message. The mystery of the lost ship and her highly skilled captain remains officially unresolved despite two additional tantalizing clues.

Search efforts to find the Pacific were launched after the ships overdue arrival. The Collins Line, which owned the missing ocean liner, sent the Alabama, and the United States Navy sent the Arctic; neither found any trace. Yet, a week after the search concluded, the Scottish steamer Edinburgh, crossing through the same area, reported debrisoak doors with white handles and wooden windows like those designed for a ships passenger cabinfloating about. The report offered little comfort to the shocked maritime community.

A large oil painting of the Pacific. (Collection of the Historical Society of Old Yarmouth)

Then in 1992, nearly 136 years after the disappearance of the Pacific, another enigmatic clue from the deep: in the seas off of North Wales, divers discovered a wreck they believed to be the Pacific. The hull of the wooden ship was lying in two large sections approximately three miles apart. Some of the cargo on the seabed matched items on the Pacifics manifest. Unfortunately, neither of the cluesthe debris or the wreckconclusively identified the Pacific.

In 1912, fifty-six years after the disappearance of the Pacific, another ocean liner, touted as the worlds newest and most luxurious, also had a fatal encounter with an iceberg. Like the unconfirmed wreck of the Pacific, the hull of the Titanic was found in two sections about a third of a mile apart. Unlike the Pacific, the sinking of the Titanic has been well documented. Survivors accounts were harrowing. The 1985 discovery of the wreck of the Titanic by a joint French-American expedition, led by Jean-Louis Michel of IFREMER and Robert Ballard of Cape Cods Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, left no doubt of the Titanics fate. The fate of the Pacific, her crew, and her captain has been consigned to a message in a bottle. The question often posed at the time was: did Captain Eldridge, in a rush to set a record time for the crossing from Liverpool to New York, push his ship too hard, ignoring adverse weather conditions? If so, will the

Next page