Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2007 by Wayne Kirklin

All rights reserved

Cover image: LV 118, todays Overfalls. Courtesy of the author.

First published 2007

Second printing 2012

e-book edition 2013

ISBN 978.1.62584.429.3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kirklin, Wayne.

Lightships : floating lighthouses of the Mid-Atlantic coast / Wayne Kirklin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

print edition ISBN 978-1-59629-350-2 (alk. paper)

1. Lighthouses--Middle Atlantic States. 2. Lightships--Middle Atlantic States. I. Title.

VK1024.M54K57 2007

387.28--dc22

2007024696

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Acknowledgements

This book is the result of the help and encouragement of many individuals. Rachael Wynne at the Columbia River Maritime Museum first suggested that I write about lightships. David Pearson, curator of that museum in Astoria, Oregon; John Byrne in Oakland, California; Shannon Fitzgerald at the Northwest Seaport in Seattle; Jerry Rome at the Huron Lightship Museum in Michigan and Greg Krawczyk at Baltimores Maritime Museum all graciously shared the lightship in their care with me.

Jim Claflin suggested many sources of information and helped me gather the illustrations. Anne Carey shared some early internet searches. Brian Wilson of the National Park Service at Harkers Island, North Carolina, contributed to my understanding of Pamlico Sound.

David Bernheisel, president of the Overfalls Maritime Museum Foundation, and his wife, Mary, our local reference librarian, both provided material as well as support.

My lovely wife, Marian, and daughter, Julie, spent many hours reviewing the manuscript while Daniel Scott kept me out of the way.

Introduction

Light boats, light vessels, lightshipsthese floating lighthouses were placed where mariners needed guidance but where it was impossible to build a permanent structure. Moored near shifting shoals, treacherous reefs or offshore where it was too far for a land-based light to reach, these craft played an indispensable part in keeping the nations waterways safe for navigation between 1820 and 1985.

This narrative is about the eighty-five ships that staffed the forty-five stations along Americas middle-Atlantic coast, ranging from New York Harbor to the southern border of North Carolina. It includes those vessels placed in the Delaware and Chesapeake Bays and the two sounds of North Carolina.

Today these lightships are largely unknown to the general public and are taken for granted by the maritime industry. Although modern technology has rendered these vessels unnecessary, the design, life and adventures of these heroic ships are fascinating.

Light vessels have existed since ancient times. In 1732 the first modern lightship was born in England when Robert Hamlin, a successful barber and ship owner with financial resources, and David Avery, a poor but resourceful man, combined their efforts to place a vessel marking a sandbar at the mouth of the Thames River.

This small, commercial ship had a lantern fixed at each end of a twelve-foot wooden pole, which was hoisted up the mast. At first the light was provided by tallow candles and later by flat wicks in oil. It was difficult to keep the vessel on station and to keep the lamps lit, but the venture proved profitable, supported by dues collected from passing ships. Seeing these results, Trinity Houseoriginally chartered by Henry XIII and charged with the duty of praying for sailors lost at sea, and as the years passed, accountable for keeping various sea marks in ordersoon assumed responsibility for this and other lightships. From this single lightship on the Thames grew a large fleet scattered over the globe, which lasted until technology made the vessels obsolete.

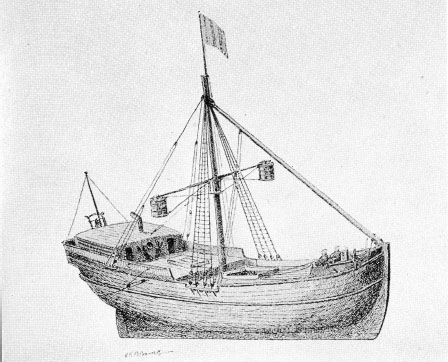

The first modern lightship, Nore, was placed in the Thames River in 1732. Courtesy of the author.

The lightship era in the United States covered 165 yearsbetween 1820, when the first small craft was stationed in the Chesapeake Bay, until 1985, when the last Nantucket lightship was decommissioned. During this time, 179 vessels were used and they covered 116 stations on Americas coasts and the Great Lakes. This period saw dramatic changes in available technology and in the role of U.S. waterways. The lightships reflected these changes.

In 1820, wind propelled ships and candles and whale oil provided light. As the years went by, the challenge of providing aids to navigation for the maritime industry remained, while the tools available to meet this challenge underwent enormous change. By 1895 the ships were powered by steam and diesel. Then electricity, radio, radar and a host of other improvements were added to modernize the way the fleet operated.

The federal governments responsibility for maritime safety started with the passage of legislation by the first session of Congress on August 7, 1789. This bill established that the federal government would support building and maintaining the countrys aids to navigation. It provided that all expenses in the necessary support, maintenance and repairs of all lighthouses, beacons, buoys and public piers erected, placed, or sunk before the passing of this act, at the entrance of, or within any bay, inlet, harbor, or port of the United States, for rendering navigation easy and safe, shall be defrayed out of the Treasury of the United States. The duties were assigned to the secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton (17891795), who appointed the commissioner of the revenue to supervise the operation. This continued until 1820, when the care and supervision of the lighthouse establishment was assigned to the fifth auditor of the treasury, Stephen Pleasonton, who held the position for almost thirty-three years.

Pleasonton has been greatly maligned by many historians. He was a man of his time. A competent, hard-working, conservative administrator, he carried this assignment along with his main duties. In addition to the lighthouse service, he was responsible for all the diplomatic and consular accounts abroad, for domestic accounts pertaining to the Department of State and Patent Office, as well as those of the census and boundary commissioners, and for adjusting claims on foreign governments. At one time he also held the duties of the commissioner of revenue. For all this, he had only nine clerks working for him.

He delegated the authority over lights and lightships to the collectors of customs. These officials supervised aids convenient to their ports. They hired, fired, found and purchased the sites for lighthouses, contracted for the building of lightships, inspected their charges and saw that they were supplied. Much of the work was performed by contract. For this the collectors received a 2.5 percent commission on disbursements, but they had to get Pleasontons approval for these expenditures. After 1822 they were allowed to spend up to one hundred dollars without prior approval. Still, during this period no one was compensated for the general administration of lighthouses, lightships and other navigational aids.