One of the occupational hazards of living in a place like Cape Cod is not always knowing where you are. The sea fog that rolls in regularly over the mud fiats and salt marshes is not entirely to blame for such chronic disorientation. Nor are the winter northeasterlies whose heavy surf and storm surges break through barrier beaches, destroy parking lots, silt up harbors, and claim waterfront property all that dislocate us.

Change is the coin of this sandy realm, and as long as we are not too close to it, such change delights us. The seasons flow in their rhythmic variety, a little out of sync with the mainland due to the oceans moderating influencewhich pleases our sense of separateness. With them come in the streaming tides of shorebirds, migrating alewives and striped bass, pack ice in Cape Cod Bay, spring peepers in the bogs, gypsy moths in the oaks, and tourists in the motels and restaurants.

Years flow and bring still broader changes, sometimes surprising, not always welcome. Bald heaths grow up to pine barrens, meadows fill in with juniper, abandoned bogs return to cedar swamps or maple swamps, oaks replace the pines, and a charming water view from the deck or terrace disappears under a rising horizon of leaves.

With these changes some new bird species appear, others grow scarcer. Fish populations fluctuate, ponds slowly silt in. New areas of tidal flats are claimed by spreading salt-marsh grasses, and each year a few more feet of the ocean cliffs topple into the surf, taking a beach cottage or two with them. Major alterations in the shape of the coastline can and do take place within a mans lifetime, adding a feeling of shared mortality in our relationship with this thin spar of glacial leavings. Yet through all this variety of natural change we also sense a continuity, not always to our liking, perhaps, but with a litting-ness and perceptible identity of its own, an interplay of great and connected forces.

To this natural change, however, we have added our own, in a way that we share with most other parts of the country. In the beginning we may have desired only to fit in to this natural scene, to enjoy what it has to offer; and yet in doing so on such a mass scale and on our own terms, we have inevitably introduced forces that have had increasing repercussions of their own.

We move here in winter onto some quiet street and find the following summer that traffic makes it unsafe to cross the road for our mail. A piece of woods where we used to walk our dogs is turned, almost overnight, into roads and building lots. An open stretch of coastal bluffs that once formed a background to our clamming on the mud flats is now clotted with condominiums. Along the Mid-Cape Highway the deer we noticed for years are one day no longer there; in their stead are houses and tennis courts. Back roads and open fields, where fox stalked and woodcock courted, all at once sprout shopping malls, golf courses, new schools, and sewage-treatment plants. And so on.

Countryside is suddenly suburban, suburban areas become densely developed, and in places our highways and urbanized areas begin to take on an aspect that makes us look hard at the exit and street signs in order to reassure ourselves we are not in Boston or New Bedford, yet. Having increased our individual mobility in both the physical and social sensethe speed and ease with which we can travel from place to place as well as the power to choose our hometownswe find ourselves less and less sure of where it is we have finally arrived.

Sometimes, watching a chickadee or a junco at the window feeder at the end of a winters day, ruffled and tossed by a wet wind and alone at the coming of darkness, I am tempted to pity its lack of human comforts and security. But the bird at least was born to the condition in which it lives. It is part of an unbroken past of this land and knows where to find itself, despite all human and natural change, during the night and in the morning. Can I say as much for myself?

What is Cape Cod today? Rural? Semirural? Suburban? Seasonally urban? Bits and parts of each, perhaps. For this particular moment, at least, the term subrurul seems as accurate as any: a patchwork of conflicting claims and uses hanging on to the remmants of a distinct rural culture that now exists almost completely in the past. And once we have named it, what then? What are we to make of it? How are we to know where we are? How are we to get here, once we have arrived?

The first step must be to see clearly what is there. This is often more difficult than it might appear, for nature has no guile, which is one of the things that makes it so hard for us to see. The bare, uncompromising face of the land is too much for us to behold, and so we clothe it in myth, sentiment, and imposed expectations.

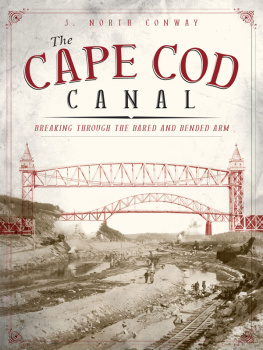

In West Brewster, for instance, where I live, the scene outside my window looks more like western Connecticut or Minnesota than like what most people think of as a typical Cape Cod landscape. No sandy shores or low dunes, no salt marshes or wide ocean waters stretch out before me. Rather, the house I built here a few years ago sits well inland, tucked into the wooded, hilly terrain of a low, broken line of glacial hills known as the Sandwich Moraine. The moraine begins west at the Cape Cod Canal, rises quickly to a height of just over 300 feet, runs east along the edge of Cape Cod Bay for some forty miles in a descending and increasingly interrupted ridge of loose till and rocks, and eventually peters out into the Atlantic at Orleans, where the arm of the Cape bends north toward Provincetown.

My house is situated near the eastern end of this moraine, on one of the lower crests about eighty feet above mean sea level. It faces south, on the north side of a roughly circular ridge of hills. These hills enclose a steep-sided bowl, or kettle hole, about a quarter of a mile in diameter, known locally as Berrys Hole.

The house is also circular in shapeoctagonal, to be exactwith wide overhangs that combine with the higher hills around it to effectively block out most of the sky from inside, even in winter. When it was built, the top of the hill was leveled off and lowered a few feet, so that the yard, which stretches south from the house to the edge of the kettle hole, appears to leap off into nothing, into some great abyss, rather than falling off, as it does, into the rather modest hollow below.

The soil in these hills is sandy by mainland standards, but compared with beach sand it is heavy with clay and studded not only with small stones but also with many large glacial boulders twenty feet or more in length, called glacial erratics. Likewise, there is little of the low seaside vegetation generally associated with a shoreline environmentbeach plum, bay-berry, pitch pine. Instead, the surrounding slopes are covered with nearly pure stands of oak, that inland tree. For as far as I can see, unbroken stands of black and white oak lift their gray, lichen-spotted trunks and branches crookedly skyward.

Since the soil is relatively poor in nutrients, the oaks tend to be dwarfed in stature and prone to insect infestations. Nevertheless, they combine with the land to create an illusion of size. Stunted and twisted by poor soil, overcutting, and salt-laden winds, these trees possess the crooked look of age. They do not dominate the low hills but fit in proportion to them, so that together they give the impression of a far greater scale than either really has. It is easy to look out at them and see full-sized forests lining the flanks of mountain ranges that stretch for miles across some formidable gorge. The Cape has its own scale, and, to one not used to it, its landscape is full of such tricks of proportion and perspective.