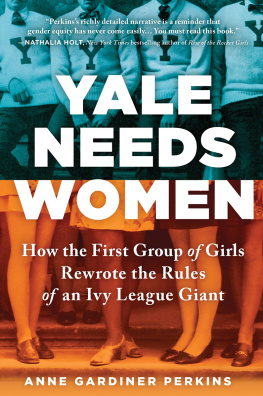

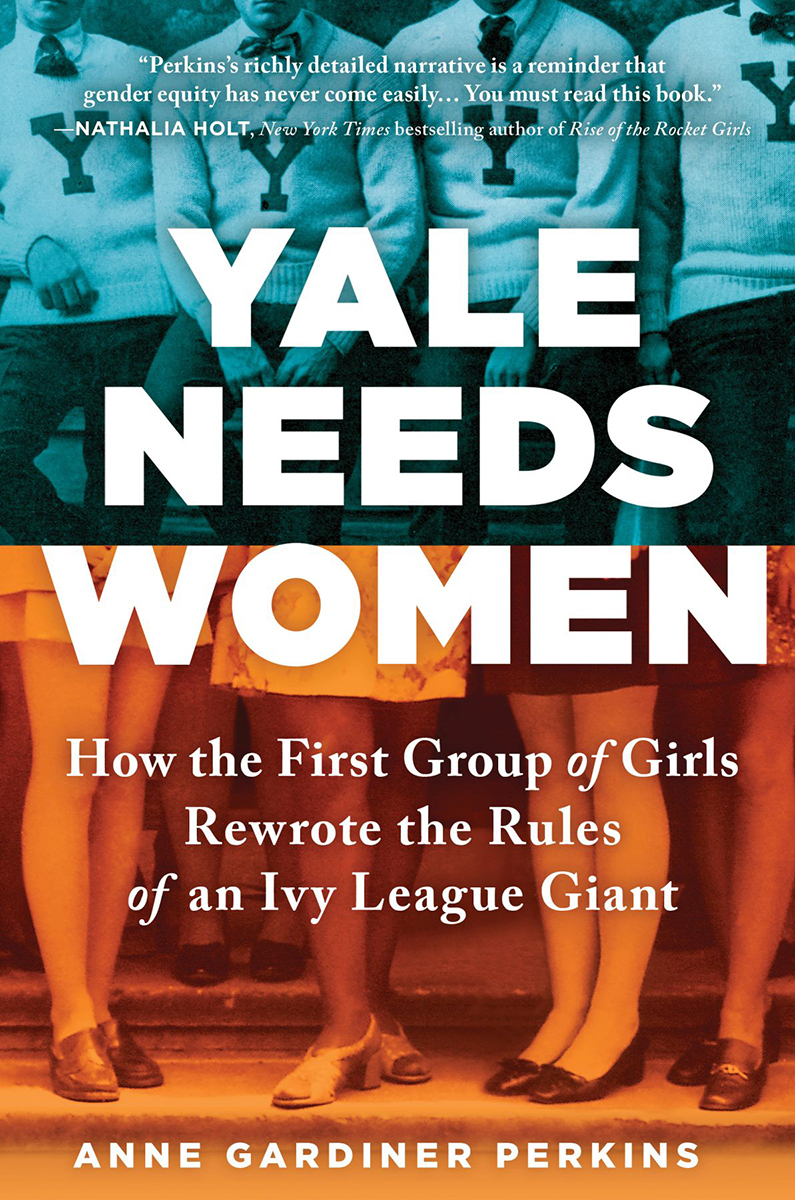

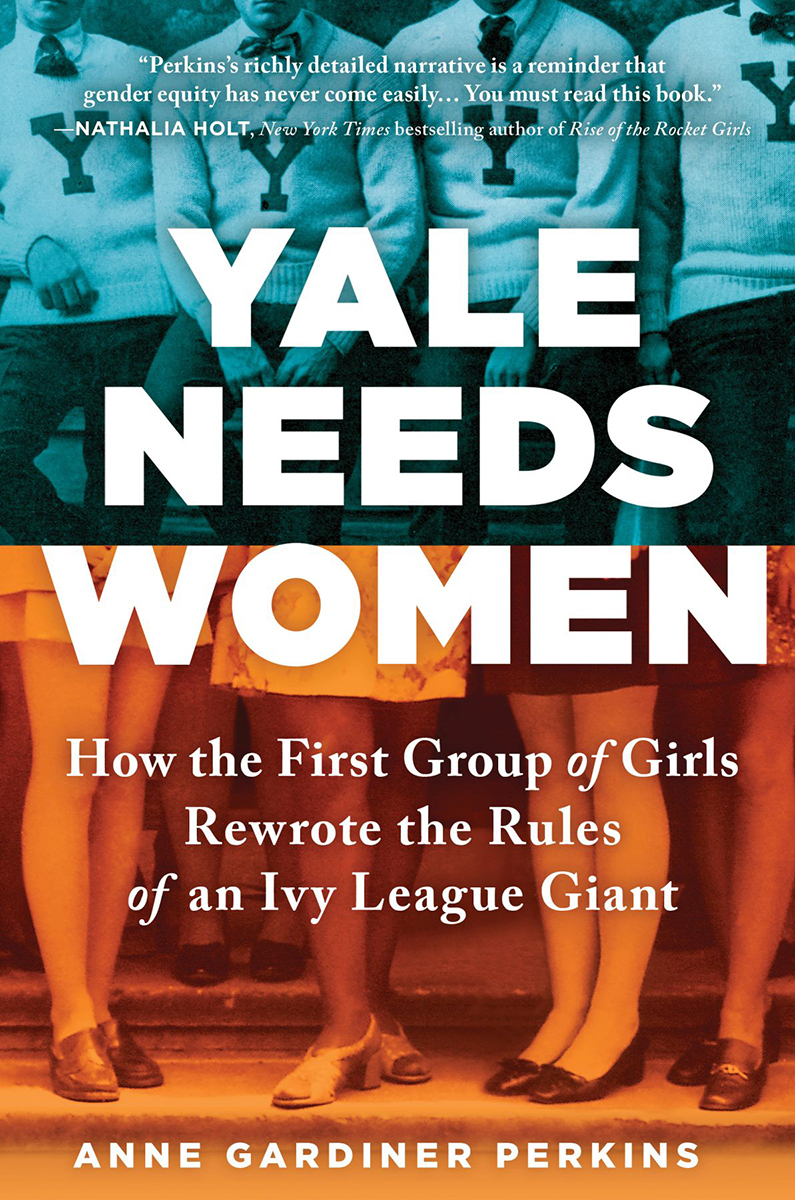

Copyright 2019 by Anne Gardiner Perkins

Cover and internal design 2019 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Lisa Amoroso

Cover images Yale University

Yale Men: 1916 Yale Cheerleading Squad. Yale athletics photographs RU 691. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.

Yale Women: 1972 Yale School of Nursing. Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library.

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewswithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought.From a Declaration of Principles Jointly Adopted by a Committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations

All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks, Inc., is not associated with any product or vendor in this book.

Published by Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60563-4410

(630) 961-3900

sourcebooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

For my family:

Rick, Lily, Robby, Mac, Ginny, and Dear

And in memory of my father, Tom, and brother, Robert

CONTENTS

Some terms in this book may strike the modern ear harshly, but since this is a historical work, I have chosen to use the words used by Yale students in 1970, including freshmen to describe first-year students regardless of gender, girls and coeds for women, blacks for African Americans, Afro-American for African American studies, homosexuals for gay students, sex for gender, and master for the heads o f Y ales residential colleges.

When I was fifty-two years old, I decided that the time had come to get my PhD. Better late than never. The idea was not entirely new. My best friend, Hazel, and I had met in our twenties, when we were both history graduate students, and I had considered getting a doctorate then. But while Hazel went on to get her PhD, I had felt pulled to different work, and after getting my masters, Id gotten a job teaching in an urban high school. Thirty years later, I was still in education, now working on policies and programs for Massachusettss public colleges and universities. I wanted to strengthen my thinking about the issues I worked on, and I knew that UMass Boston had a well-regarded higher education program. Once again, the doctorate beckoned.

So I began. Monday through Thursday, I worked at my job on Beacon Hill. Fridays, I went to class at UMass Boston. Weekends, I studied. My husband, Rick, did all the cooking andlets be honestevery other household chore too. But it was exciting to be back in school again.

I never intended to write a history dissertation, though Hazel would tell you that my doing so was entirely predictable. I planned to research some practical topic, one tied more directly to my job, but in my first fall semester, I took a required course on the history of higher education. Needing a topic for the final class paper, I wondered, What about those first women students who arrived at Yale in 1969? I bet there are some amazing stories there. The idea was not as random as it might sound. You see, I had gone to Yale too.

I arrived as a freshman in 1977, eight years after the first women undergraduates. I studied history and wrote for the Yale Daily News. I covered womens ice hockey and eventually the presidents beat. In my junior year, I became editor in chief. Yet throughout that whole time, I knew nothing about the women at Yale who came before me and all the challenges they faced when they got there.

Decades later, I searched for a book that would tell me about Yales first women undergraduates, but the women were missing from histories o f Y ale in that era. The books focused instead on the decision to let women in, as if that were the end of the story. But what happened next? Thats what I wanted to know. Here was a college that had been all male for 268 years, and then, suddenly, the first women students arrived. Historian Margaret Nash calls such moments flashpoints in history, times when the bright light of a sudden change illuminates all around it and everything, for a time, seems possible. In 1969, the U.S. womens movement had just begun. The Black Power movement was changing how Americans saw race. And into that moment stepped the first women undergraduates at Yale.

I took a day off from work and drove to New Haven to see what I might find in the Yale archives, and after that, there was no turning back. The story was just too compelling. I went back to the archives a second time, a third, a fourth, still more, now for a week at a time. Eventually, I realized that if I really wanted to understand what had happened at Yale in that flashpoint of history, I needed to talk to the women who had lived through it.

and she was only half kidding. But by that point, getting this history right had become as important to me as it was to her. The women who go first and speak out help shape a better world for all of us, yet all too often their stories are lost. I was not going to let that happen to this story.

I went back to the archives again and pored through box after box of documents. I read hundreds of old newspaper stories and compiled thousands of pages of notes. For me, though, the real gift of this book has been the remarkable women I came to know in writing it, the first women undergraduates at Yale. This is their story. I am honored to be the one to tell it.

Anne Gardiner Perkins

Boston, 2019

268 Years of Men

Yale was still an all-mens college back then, and one of the only ways to find a girlfriend was to frequent the mixers that brought in busloads of women each weekend from elite womens colleges like Vassar and Smith. On Saturday nights, the buses rolled into Yale at 8:00 p.m., each with their cargo of fifty girls. At midnight, the girls returned from whence they came. In the four hours in between, the Yale men sought to make their match. Guys who had girlfriends already would show up at the Saturday football games with their girls on their arms and then appear with them afterward in the dining hall or a local restaurant. But for the rest of the week, Yale undergraduates lived their days in a single-sex world.

To picture Yale as it was at the time, imagine a village of men. From Monday through Friday, students attended their men-only classes, ate meals in their men-only dining hall, took part in their men-only extracurricular pursuits, and then retired to their men-only dorms. Yale admitted scatterings of women graduate and professional students in 1967, but Yale College, the heart of the university, remained staunchly all male. The ranks of faculty and administrators who ran the school were nearly all men as well. If you were to peek through the door at any department meeting, the professors seated around the table would invariably be white men in tweeds and casually expensive shoes, as one o f Y ales rare black professors observed. Yale was an odd place, at least to a modern eye, but since its founding in 1701, Yale had always been a place for men.

Next page