PART 1: ASIA

Mystery Woman of Jakarta

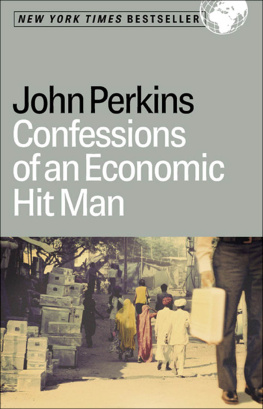

I was ready to rape and pillage when I headed to Asia in 1971. At twenty-six, I felt cheated by life. I wanted to take revenge.

I am certain, in retrospect, that rage earned me my job. Hours of psychological testing by the National Security Agency (NSA) identified me as a potential economic hit man. The nation's most clandestine spy organization concluded that I was a man whose passions could be channeled to help fulfill its mission of expanding the empire. I was hired by Chas. T. Main (MAIN), an international consulting firm that did the corporatocracy's dirty work, as an ideal candidate for plundering the Third World.

Although the causes for my rage are detailed in Confessions of an Economic Hit Man, they can be summarized in a few sentences. The son of a poor prep-school teacher, I grew up surrounded by wealthy boys. I was both terrified and mesmerized by women and, therefore, shunned by them. I attended a college I hated because it was what my mother and father wanted. In my first defiant act, I dropped out, landed a job I loved as a copy boy on a big city newspaper, and then, tail between my legs, returned to college in order to avoid the draft. I married too young because it was what the one girl who finally accepted me demanded. I spent three years in the Amazon and Andes as an impoverished Peace Corps volunteer once again forced to evade the draft.

I consider myself a true and loyal American. This too contributed to my rage. My ancestors fought in the Revolution and most other U.S. wars. My family was predominantly conservative Republican. Having cut my literary teeth on Paine and Jefferson, I thought a conservative was someone who believed in the founding ideals of our country, in justice and equality for all; I was angered by the betrayal of these ideals in Vietnam and by the oil companyWashington collusion that I saw destroying the Amazon and enslaving its people.

Why did I choose to become an EHM, to compromise my ideals? Looking back, I can say that the job promised to fulfill many of my fantasies; it offered money, power, and beautiful womenas well as first-class travel to exotic lands. I was told, of course, that I would be called upon to do nothing illegal. In fact, if I did my job well, I would be lauded, invited to lecture at Ivy League schools, and wined and dined by royalty. In my heart I knew that this journey was fraught with peril. I was gambling with my soul. But I thought I would prove the exception. When I headed for Asia, I figured I would reap the benefits for a few years, and then expose the system and become a hero.

I have to admit, too, that I had developed a fascination for pirates and adventure at an early age. But I had lived the opposite type of life, always doing what was expected of me. Other than quitting college (for a semester), I was the ideal son. Now it was time to rape and pillage.

Indonesia would be my first victim...

The earth's largest archipelago, Indonesia consists of more than seventeen thousand islands stretching from Southeast Asia to

Australia. Three hundred different ethnic groups speak more than 250 distinct languages. It is populated with more Muslims than any other nation. By the close of the 1960s we knew that it was awash in oil.

President John F. Kennedy had established Asia as the bulwark of anticommunist empire builders when he supported a 1963 coup against South Vietnam's Ngo Dinh Diem. Diem was subsequently assassinated and many people believed the CIA gave that order; after all, the CIA had orchestrated coups against Mossadegh of Iran, Qasim of Iraq, Arbenz of Venezuela, and Lumumba of the Congo. Diem's downfall led directly to the buildup of U.S. military forces in Southeast Asia and ultimately the Vietnam War.

Events did not transpire the way Kennedy had planned. Long after the U.S. president's own assassination, the war turned cata-st rophic for the United States. In 1969, President Richard M. Nixon initiated a series of troop withdrawals; his administration adopted a more clandestine strategy, focused on preventing a domino effect of one country after another falling under communist rule. Indonesia became the key.

One of the principal factors was Indonesia's President Haji Mohammed Suharto. He had earned a reputation as a stalwart anti-Communist and a man who did not hesitate to use extreme brutality in executing his policies. As head of the army in 1965 he had crushed a Communist-instigated coup; the subsequent bloodbath claimed the lives of 300,000-500,000 people, one of the worst politically engineered mass murders of the century, reminiscent of those of Adolf Hitler, Josef Stalin, and Mao Tse-tung. Another estimated one million people were thrown into jails and prison camps. Then, in the aftermath of the killings and arrests, Suharto took over as president, in 1968.

When I arrived in Indonesia in 1971, the goal of U.S. foreign policy was clear: stop communism and support the president. We expected Suharto to serve Washington in a manner like that of the shah of Iran. The two men were similar: greedy, vain, and ruthless. In addition to coveting its oil, we wanted Indonesia to set an example for the rest of Asia, as well as for the entire Muslim world.

My company, MAIN, was charged with developing integrated electrical systems that would enable Suharto and his cronies to industrialize and become even richer, and would also ensure longterm American dominance. My job was to create the economic studies necessary to obtain financing from the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

Soon after my arrival in Jakarta, the MAIN team met at the elegant restaurant on the top floor of the Hotel Intercontinental Indonesia. Charlie Illingworth, our project manager, summarized our mission: "We are here to accomplish nothing short of saving this country from the clutches of communism." He then added, "We all know how dependent our own country is on oil. Indonesia can be a powerful ally to us in that regard. So, as you develop this master plan, please do everything you can to make sure that the oil industry and all the others that serve itports, pipelines, construction companiesget whatever they are likely to need in the way of electricity for the entire duration of this twenty-five-year plan."

Most government offices in Jakarta in those days opened early, around seven A.M., and shut their doors at about two P.M.

Their employees broke for coffee, tea, and snacks; however, lunch was postponed until the closing hour. I made a habit of rushing back to the hotel, changing into my bathing suit, heading for the pool, and ordering a tuna fish sandwich and cold Bintang Bara, a local beer. Although I dragged along a briefcase stuffed with official papers I had collected during my meetings, it was a subterfuge; I was there to work on my tan and ogle the beautiful young bikini-clad women, mostly American wives of oil workers who spent their weekdays in remote locations or executives with offices in Jakarta.

It did not take long for me to become enamored with a woman who appeared to be about my age and of mixed Asian-American heritage. In addition to her stunning physique, she seemed unusually friendly. In fact, sometimes the way she stood, stretched, smiled at me while ordering food in English, and dove into the pool appeared flirtatious. I found myself quickly turning away. I knew I must be blushing. I cursed my puritanical parents.

Every day, around four o'clock, approximately an hour and a half after my arrival, she was joined by a man who, I was certain, was Japanese. He arrived dressed in a business suit, which was unusual in a country where formal attire generally consisted of slacks and a well-pressed shirt, often made from local batik cloth. They chatted for a few moments and then departed together. Although I searched for them in the hotel bars and restaurants, I never saw them together or alone anywhere except at the pool.