Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my parents

Thou shalt not kill.

EXODUS 20:13

Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises,

Sounds, and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments

Will hum about mine ears; and sometime voices

That, if I then had waked after long sleep,

Will make me sleep again: and then, in dreaming,

The clouds methought would open, and show riches

Ready to drop upon me that, when I waked,

I cried to dream again.

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, The Tempest

This is a true story. Although some names have been changed, no scenes have been invented. Items of text appearing in direct quotes come from interviews given to me or, in a couple of instances, interviews recorded for television. Otherwise, they are taken from documents drawn up by, or for, Panamas state or district prosecutors. All translations from the original Spanish into English are my own. Some passages quoted from blogs, e-mails, police notes, letters, and flyers have, occasionally, been corrected for spelling and grammar.

Where witnesses to events gave me conflicting versions, I chose the most credible source or the version I thought most likely. Any errors, of course, are my own.

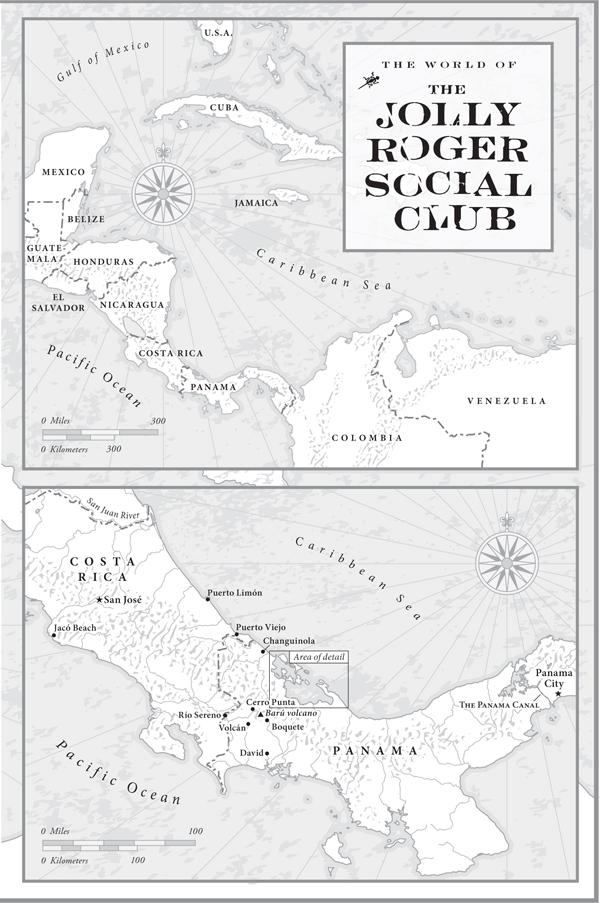

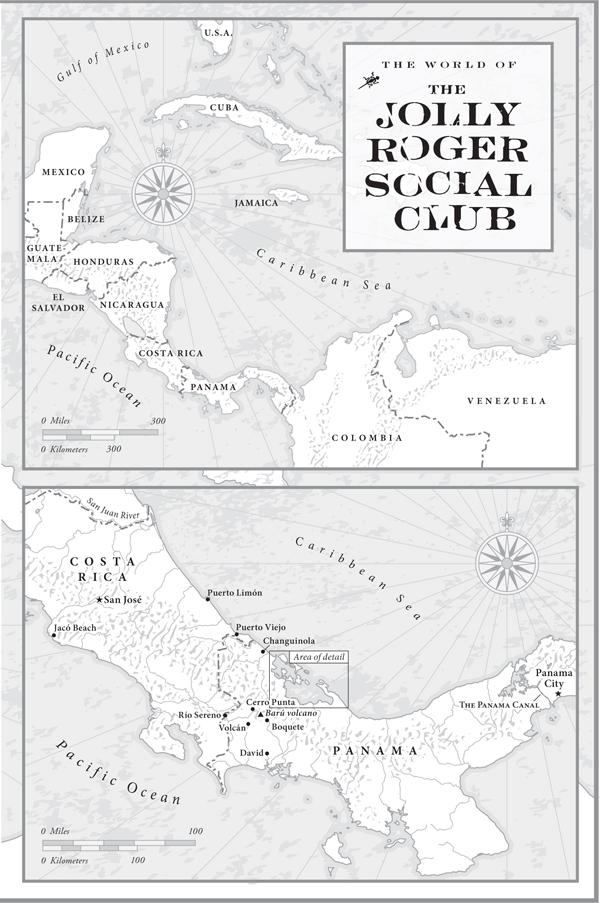

In 2011, my editor at the Financial Times asked me to write a feature on the real estate boom in Panama. I had just spent a few days in the country and had found it surprisingly modern and bustling. Panama occupies the narrow isthmus separating the Caribbean Sea from the Pacific Ocean. Its canal, completed in 1914a remarkable piece of engineering in any age, and a considerable source of revenueimmediately set the country apart from its neighbors.

In Panama City, scores of high-rises poked at the sky on the waterfront, in a Latin copy of Dubai or Singapore. One of them was a dramatic, sail-shaped seventy-story tower called the Trump Ocean Club Panama, and it had just opened for business. Meanwhile, plans were afoot to turn a 3,460-acre former US Air Force base near the canal into a new urban environment with sleek business parks, malls, and thousands of new homes. It was part of the general ambition to transform this small, ideally located nation into a hub of the Americas, the perfect place for blue-chip corporations to locate their Latin American operations. I asked the communications director of the project to develop the old air force base if Panama, long considered a developing country, was now about to join the ranks of the first world. Yes, he replied, absolutely!

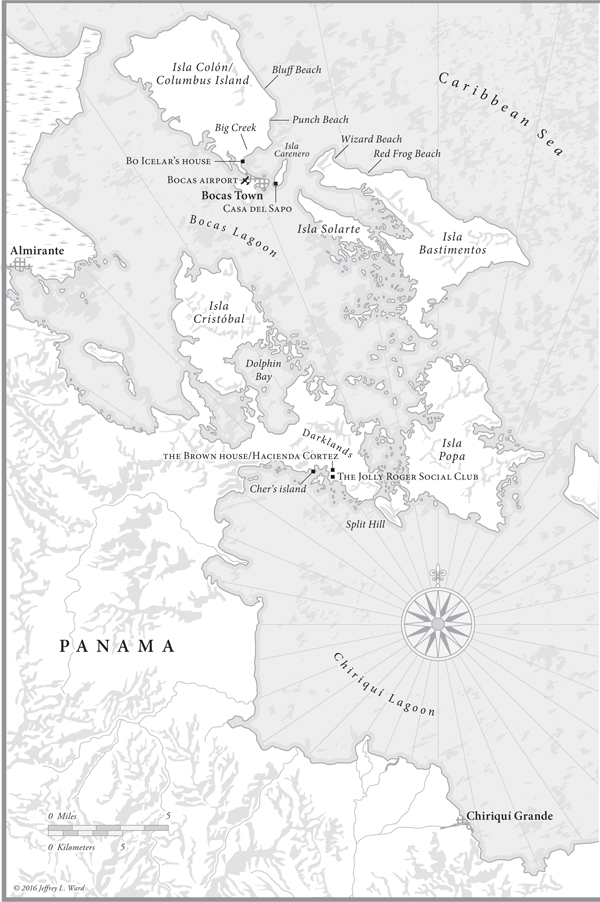

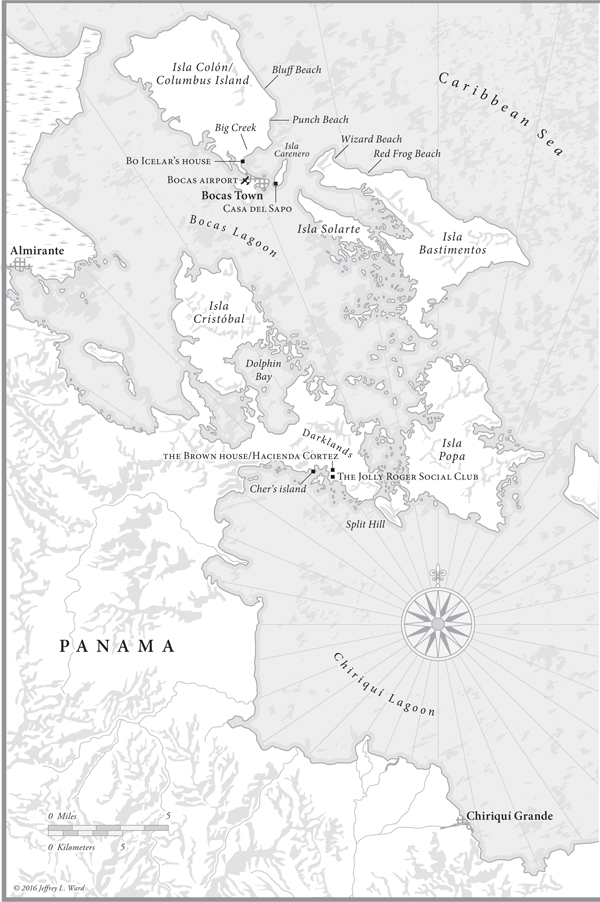

While I was writing my newspaper feature, I came across the story of an American expat known as William Wild Bill Corteza fearsome-looking young man in the photosaccused of killing five of his compatriots in Bocas del Toro, a remote archipelago off Panamas Caribbean coast, near the border with Costa Rica. Cortez had been apprehended on the run in Nicaragua, and promptly flown back to Panama to face the music. Under interrogation, he soon admitted to killing a total of six people: five American citizens and a Thai woman, married to one of the Americans. Cortezs victims had all been shot in the head, execution-style. His wife and presumed accomplice, Jane Cortez, was a tight-lipped young woman who, like Wild Bill, had been born and raised in North Carolina. At their home in Bocas del Toro, police found a stash of gold dental fillings and crowns, ammunition for an AK-47 assault rifle, and a number of credit cards and checkbooks that were not theirs. Bill had been described by a fellow expat as the worlds first capitalist serial killer.

In 2011, there were an estimated two thousand expats living more or less permanently on the tropical islands of Bocas del Toro, around two-thirds of them Americans. No one knew the true figure, but the number was certainly growing every year. Many homes were only accessible by boat. I wondered what kind of expat community Bocas del Toro was. Bloggers made arch comments about the kind of newcomer who washed up there. It turned out that Bocas del Toroliterally Mouths of the Bull, or Bocas for shortis a place of sun-kissed beaches and pristine jungle. But scratch the surface and the islands of Bocas appear a whole lot more sinister: for thirty years or more they have been a key transit point for drug shipments from Colombia to North America. They were also known for their property scams. Among other things, unscrupulous realtors went as far as hawking tracts of land to people who already owned them, and trying to sell sandbars, only visible at low tide, hoping the gullible buyer wouldnt come back when the tide was high and the sandbar was underwater.

Most of all, the islands of Bocas del Toro had become a hangout for the type of expat who appreciates anonymity and who might want to disappearfrom ex-spouses, tax authorities, the police. Many of these people adopt a false name, and few others seem to care. The principle of live and let live has been taken to the extreme in Bocas, another expat told me. Everyone here, he said, came because back home they were either Wanted, or unwanted. Some of them had precious few friends and family.

After 9/11, Bocas saw a huge new influx of expats. Even if it was the middle of nowhere, it was far away from likely terrorist targets. It was a place whose isolation forced an almost total self-reliance. It attracted the kind of person, often in their forties or fifties, the tail end of the baby boomers, who had given up on the idea that any government was going to take care of them.

From around 2002 onward, Bocas Townthe only large settlement in the chain of islands, with bars and restaurants right on the waterbecame a place to party. You could buy land or a house and, in a year or two, sell up and double your money. This was an accentuated version of what was happening in the United States: in the period preceding the housing crash of 2007, many American states saw years of double-digit house-price growth. A lot of folks thought there was no reason why house prices could not go up forever.

The disturbing Cortez story also connected with that global property boom and bust. Soon after he arrived in Panama in 2006, Wild Bill portrayed himself as a real estate developer with plenty of cash to spend, advertising HASSLE FREE AND FAST CLOSINGS in a local English-language newspaper. In Bocas it was known that Cortez was solvent and on the lookout for houses to buy. Piecing together accounts from locals and Panamanian and US news reports, I began to suspect that Cortezs numerous murdersif, indeed, he was the perpetratorhad property fraud at their heart.

Besides his real estate business and a Harley-Davidson repair shop, Cortez also ran a bare-bones drinking den called the Jolly Roger Social Club. The bar, open weekends only, was located four hundred yards from Bill and Janes own home. The raucous parties at the Jolly Roger were the stuff of local legend. Some expats would not want to be seen within a mile of the bar, such was its reputation. But many others loved the place and its boisterous drinking games, and courted the company of Wild Bill himself. Cortez, with his beefed-up physiqueit was widely assumed he took steroidslong blond hair, and Viking helmet, was defiantly larger than life. And so was his life story. His father was Mexican and had been an ambassador. He owned oil fields in Texas. He had a $10 million trust fund. Meanwhile, Jane said she was a veterinarian, but when shown a sick Jack Russell terrier she said she couldnt help as she only treated big animals like cows, not dogs. The Jolly Roger Social Club flew a skull and crossbones and its motto was: Over 90% of our members survive . One oddity about the place was that, for a successful, even hard-nosed businessman, Cortez appeared to run his dive on what could only be described as altruistic lines. All the time he spent serving drinks behind the bar, and in the kitchen preparing greasy finger food, made a profit of little more than $20 a night. On top of that, the Cortezes had to pay for electricity and upkeep of the wooden structure, jutting out on stilts over the Caribbean.