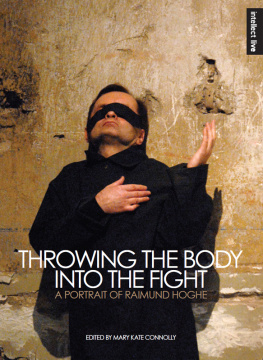

THROWING THE BODY INTO THE FIGHT

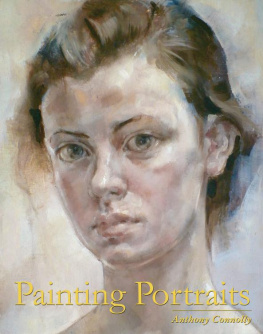

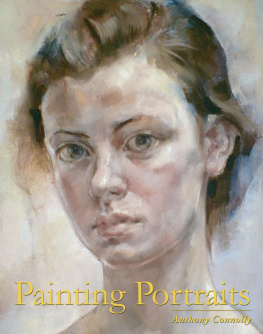

A PORTRAIT OF RAIMUND HOGHE

Si je meurs laissez le balcon ouvert - Emmanuel Eggermont & Ensemble

Pas de Deux

Contents

by Mary Kate Connolly

by Gerald Siegmund

Stay a While: Raimund Hoghes Histories

by Dominic Johnson

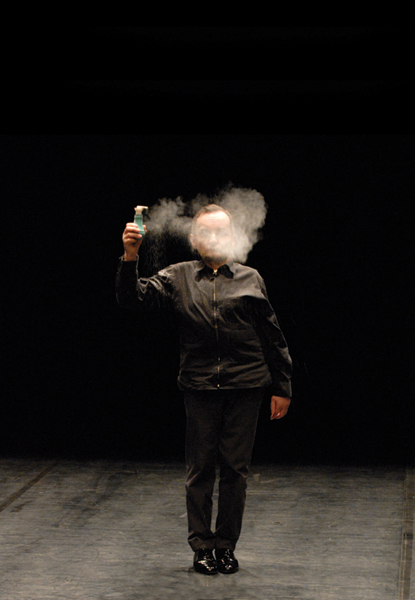

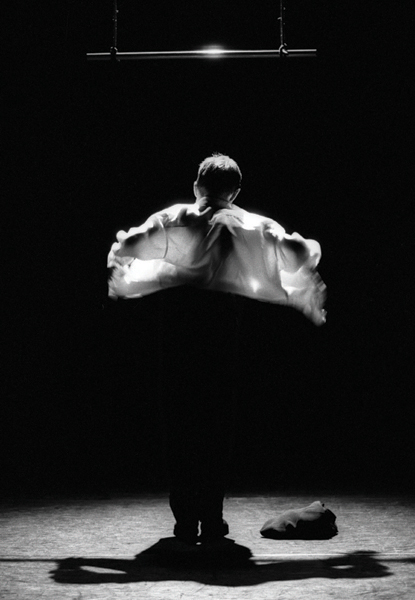

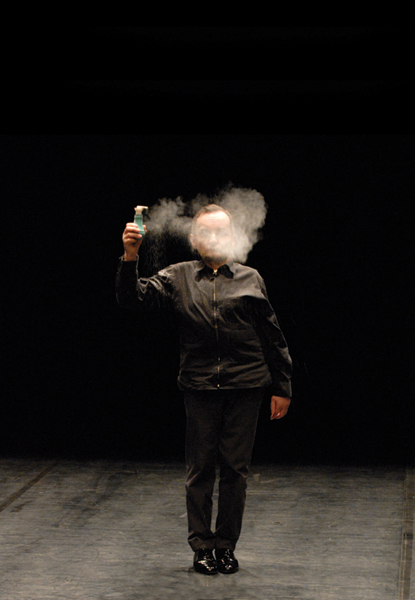

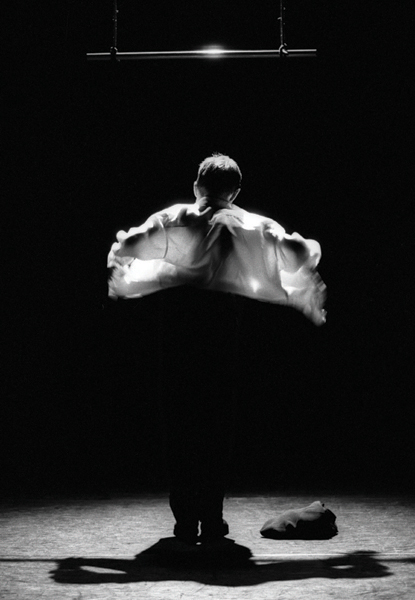

Pier Paolo Pasolini wrote of throwing the body into the fight. These words inspired me to go on stage. Other inspirations are the reality around me, the time in which I live, my memories of history, people, images, feelings and the power and beauty of music and the confrontation with ones own body which, in my case, does not correspond with conventional ideals of beauty. To see bodies on stage that do not comply with the norm is important not only with regard to history but also with regard to present developments, which are leading humans to the status of design objects. On the question of success: it is important to be able to work and to go your own way with or without success. I simply do what I have to do.

Raimund Hoghe

Swan Lake, 4 Acts

Bolro Variations

Mary Kate Connolly

Editors Note

With every project comes a moment when all seems lost. For me, such a time came deep into the process of compiling this book. Following an arduous journey from attempting to get the publication underway, to the joy of commissioning texts from writers and finally receiving them, of travelling to interview Raimund and write on his work, I realised that somehow, I had no idea how to proceed. Faced with the task of compiling this portrait of the artist, I feared destroying the very thing I had set out to preserve; that of the complex and ethereal space which is Raimund Hoghes theatre.

My first encounter with Raimunds work was Swan Lake, 4 Acts. In endeavouring to distil my response to this performance, I identify greatly with Martin Hargreaves description of becoming undone. I was brimming with words, yet rendered speechless. During subsequent research on Raimund, I became acutely conscious of the capacity for words to illuminate, and yet also do strange violence to an experience of theatre which is pleasingly impossible to pin down. This is true perhaps of all performance, but in the case of Raimund Hoghes work it seems particularly so. Above all, I was struck by the strength of feeling provoked in those who write about this artist (myself included), and at times, the sharp divide in opinions on his work. Writing in 2001, Gerald Siegmund suggested that we should thank [Hoghe]for his art, whereas in 2007, UK dance critic Jenny Gilbert (reviewing Sacre - The Rite of Spring for The Independent newspaper) concluded that Hoghe argues his point bizarrelyThe entire event is so perversely undramatic, so devoid of context, you can imagine whatever you like.

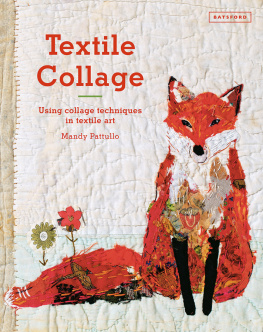

Of course severe differences in opinion regarding performance are nothing new or particularly noteworthy. But perhaps what registered for me in the face of these divergences was the desire to tread softly, and not endeavour in the collation of this publication, to forge a seamless or exhaustive account of Raimund Hoghe and his work. Rather, this book aims to operate as a collage; it seeks to draw an incomplete and fragmented portrait of Hoghe, through the assemblage of a variety of international voices. These voices have different registers, tones, preoccupations, and there is a deliberate editorial attempt to allow these to co-habit.

In commissioning the content for this book, it felt important to draw from a variety of sources, and furthermore, that the writers contributing could offer differing international perspectives. Currently, Raimund Hoghe enjoys much critical acclaim; he performs across Europe, and has presented work in New York, Tokyo and Rio de Janeiro. Awarded the French Prix de la Critique in 2006 for Swan Lake, 4 Acts, and the title Dancer of the Year in 2008 (by the magazine Ballet-Tanz), he is now predominantly billed within the realm of dance performance. This was not always the case however, and the writers within this book have encountered Hoghes work in different contexts and at different times. Lois Keidan has written of the negative reception which his early work received in Germany and Austria, and by contrast, the positivity with which Meinwrts was greeted when programmed in 1994, within the context of Live Art, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London. Mercifully, the demand for the categorisation of Hoghes work no longer appears a significant concern among critics, but the evolution and shift in the ways in which his work is viewed strengthened the need for a diverse collection of contributors spanning time and geographical location.

Whilst writers such as Gerald Siegmund, Martin Hargreaves and Laurent Goumarre hail from Germany, the United Kingdom and France respectively, more importantly, they have encountered Hoghes work in different contexts and at varying times across Hoghes career. Thus their points of reference contrast, and so too their central thematic concerns. For his contribution, Gerald Siegmund has re-visited a lecture he delivered during a conference held at Kaaitheater (Brussels) in 2004. Eight years on from the original lecture, he adjusts his argument slightly, and so the writing emerges both from a historical perspective, whilst simultaneously being relocated to the current context.

Besides the need for the writing to span time and place, a number of seemingly valuable themes surfaced in curating Throwing the Body into the Fight. Once again, these do not masquerade as an exhaustive or definitive list, but provide focal points for the discussion of Hoghes work.

Meinwrts

People say he is too small for his age. Too delicate, too weak. And there is something else, barely noticeable: a slight curvature of the spine, a scarcely visible arching that makes them afraid. It becomes more and more pronounced, and theres no way of stopping it. Theres not much we can do, the doctors say, prescribing massages and gymnastic exercises and an annual period of rehabilitation at the seaside. Thats good for the boys bronchial tubes, they say; it will make it easier for him to breathe. When he was younger still, his mother had once sewn him a sailors outfit. At the cinema they watched the popular movies, movies transporting them to far-away places, down South, to the sun and the sea. The new films started on Fridays and Tuesdays. The sea was always as blue as the sky. (Meinwrts, 1994)

The first of these themes was an exploration of the body; not only how Hoghes particular body (with severe curvature of the spine) might occupy the space of performance, but more vitally, to extend the question beyond this realm. Martin Hargreaves seeks to understand how it is not so much Hoghes body, or not only his body, that enters the fight but how it is

Next page