By the same author

Non-fiction

H UGH K INGSMILL

U NRECEIVED O PINIONS

L YTTON S TRACHEY

A UGUSTUS J OHN

B ERNARD S HAW

B ASIL S TREET B LUES

W ORKS ON P APER

Fiction

A D OGS L IFE

Editor

T HE B EST OF H UGH K INGSMILL

L YTTON S TRACHEY BY H IMSELF

T HE A RT OF A UGUSTUS J OHN

with Malcolm Easton

T HE G ENIUS OF S HAW

T HE S HORTER S TRACHEY

with Paul Levy

W ILLIAM G ERHARDIES G ODS F IFTH C OLUMN

with Robert Skidelsky

E SSAYS BY D IVERS H ANDS

New Series: Volume XLII

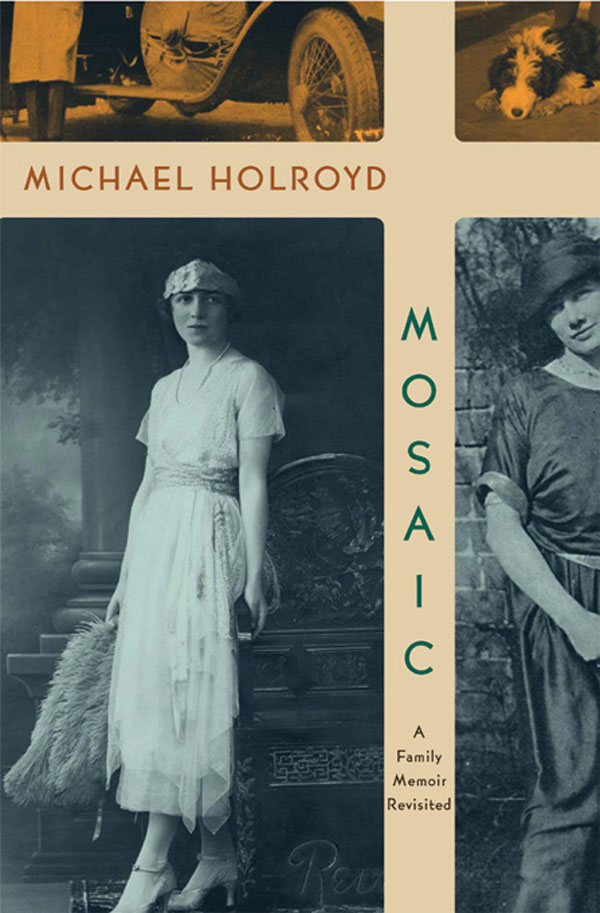

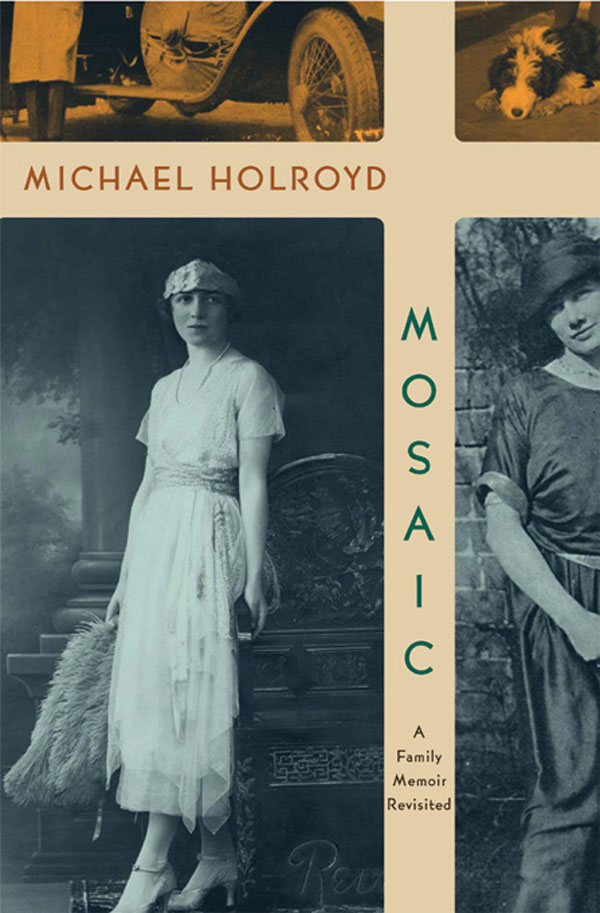

Mosaic

A Family Memoir

Revisited

MICHAEL

HOLROYD

W. W. N ORTON & C OMPANY

New York London

For you

my readers

These fragments I have shored

against my ruins.

T. S. Eliot

The Waste Land

Contents

Acknowledgements

Among the many people to whom I am grateful for help with the research for this book are Mrs M. S. Adams, Stella Astor, Neil Austin, Michael Barber, Mark Beaumont-Thomas, Lilla Bek, Alan Bell, Anthony Blond, Peter Blond, Pearl Brewis, Carmen Callil, Peter Calvert, Honor Clerk, Sarah Constantine, Diana Dracopoli, Jack Dracopoli, Margaret Dracopoli, Patricia Ellegard, Vicki Feaver, Michael Foss, Sally Gaywood, Mariolina Gent, Myfi Heim, Ann Johnson, Jim Knowlson, Judith Landry, Murray Last, Paul Levy, Linda Lloyd Jones, T. G. Lyttelton, Andrew McCall, Clare Michell, John Michell, Betty Parsons, Eduardo SantAnna, Jennifer Scarf, David Shepherd, Robert Skidelsky, Hilary Spurling, David Sutton, Robin Treherne-Thomas.

I have also relied on the expertise of several local historians including Judy Collingwood, Pamela Peskett, Janet Rowarth and J. Derek Skepper, all of whom made vital contributions to my researches.

I would also like to record my thanks to libraries and institutions that have assisted me: Roy Andrews at Andrews, Gwynne and Associates; the Beverley Local Studies Library; the British Racing Drivers Club; Geoffrey J. Crump and the Cheshire Military Museum; Mrs P. Hatfield, archivist at Eton College Library; W. J. B. Meakin and Geoffrey Grant at Grant Saw and Son; the Reference Library at Hull; the Local Studies Centre of the Kensington and Chelsea Central Library; Simon Jones, curator at the Kings Regiment; Alfred and Ewart Longhurst; the National Maritime Museum; the Royal Academy of Arts; the Royal Motor Yacht Club; the Royal Society of Marine Artists; the Royal Solent Yacht Club; the Royal Thames Yacht Club; Daphne Todd, president of the Royal Society of Portrait Painters; and Trinity Hospice.

I owe much, as ever, to Sarah Johnson for deciphering my text and enabling me to present it to my publishers in legible form. At Little, Brown I must thank my editors, Richard Beswick, Caroline North and Viv Redman, and proof-reader Kate Truman for continuing this process for the benefit of readers. I would also like to thank Viv Mullett for drawing the family trees.

Finally, and most sincerely, I must pay tribute to the patience, generosity and goodwill of my wife, Margaret Drabble, without which this book would never have come into existence.

List of Illustrations

Preface

OUR FAMILIES, RIGHT OR WRONG

This is a book of surprises at any rate it has surprised me. Some may think it eccentric: I prefer the word original. Initially it arose out of letters I received from readers of my family memoir, Basil Street Blues , which was published in 1999. I thought of it at first as a sequel or postscript, even as a postmodern interactive work. Beginning as a requiem, it evolved into a love story, then a detective story, finally a book of secrets revealed: an independent companion volume which I have composed so that anyone can follow the narrative without having read, or remembered, the earlier book.

What it shows, I believe, is the strange interconnectedness of our family lives. We are often reminded that we have only to go back a few generations to find that we are, all of us, approximately related one to another which is why other peoples stories, however puzzling or extreme, contain so many echoes of our own dreams and experiences. Nevertheless, it has been an odd experience learning from strangers about events involving my own relations, as well as finding myself having more knowledge of some fathers and grandmothers than their own daughters or grandsons have. We live in a forest of family trees, and the branches reach out in complicated paths over unexpectedly long distances. In tracing some of these connections and involvements as far as I can, I have tried to present an anatomy of well-researched, if wayward, family history.

The characters in this book are all ordinary people. But their exploits and adventures reveal how compelling fantasies, as well as mundane facts, guide our lives. It is how a writer mixes these facts and fantasies that divides the historian from the novelist, and determines whether a book is classified as fiction or (that most mysterious category) non-fiction.

Illuminations from the Past

A LAST GLIMPSE OF MY FATHER

I took a postchaise to Uttoxeter, and going into market at the time of high business, uncovered my head, and stood with it bare an hour before the stall which my father had formerly used, exposed to the sneers of the standers-by and the inclemency of the weather.

Samuel Johnson

The End.

After three years I had finished. I had written it all after the old fashion, with a pen and paper, then sent it off to Sarah Johnson. Over many years she has made herself indispensable at this stage of a book the only person, or so I believe, since she tells me this, who can read my writing and (which is sometimes more illegible) my typewriting. She puts it on to a disk and, after much to-ing and fro-ing, time for second or third thoughts and so on, I have the print-out before me several copies of it. The time is now approaching for me, in the unconvincing guise of a modern technological man, to edge towards my publisher. But for myself, I believe, I have finished. It is the end. I sit back then suddenly some words from Samuel Beckett come floating into my mind. Finished, its finished, nearly finished, it must be nearly finished. And then some more words: How often I have said, in my life... It is the end, and it was not the end. Yet surely this really was the end, my signing off.

I called the book Basil Street Blues . It was not, of course, quite the end. There would be editing, proof-reading, and then publication. For the publishers that would be the end and for readers the beginning. But for me, its author, this felt like the end. It was the late summer of 1998, and I was free. Almost free.

As I made arrangements to deliver the typescript to my literary agent, a chieftain amongst agents, the ferociously named, mild-mannered Caradoc King, I began thinking over what I had done. Certainly I had not done anything quite like it before. This was a genuine variation on what I had spent my career doing: writing peoples lives. For this time it was my own life I had written. The typescript contained over a hundred thousand words. It sat there on the table. My life.

When people say that everyone has a book in him or her, they usually mean an autobiography in whatever form it comes: a poem, a quest, documentary, confession, film or play, roman clef. Mine was a family memoir.

Writers are naturally protective over their powers of language. If the magic works, then these mysterious marks we put on paper and send out like messages in a bottle can affect men and women, readers we never hear or see for the most part and do not know, making them laugh or cry, feel and think. Using this ancient technology, even the dead can communicate with us. Like the fabulous garment Prospero puts on in his cell, the writers art invades our dreams, raises sea-storms and summons kings, makes them excite or entertain us, chasten, enchant. It is a mantle, too, lending writers many disguises which, like the chameleons ability to change colour, help us find a way through difficulties and dangers.

Next page