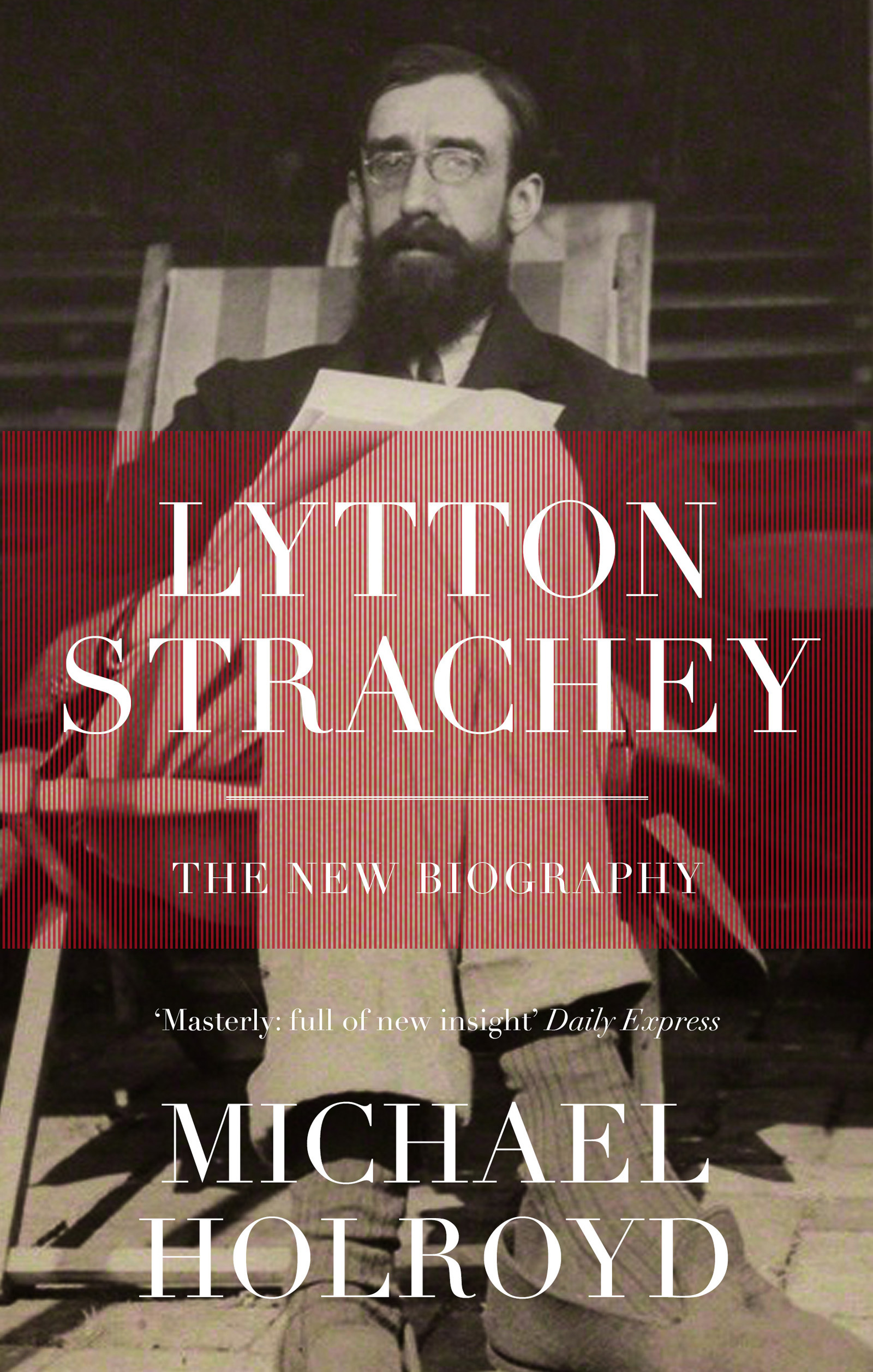

Holroyd Michael - Lytton Strachey: A Critical Biography

Here you can read online Holroyd Michael - Lytton Strachey: A Critical Biography full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1967, publisher: Head of Zeus, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Lytton Strachey: A Critical Biography

- Author:

- Publisher:Head of Zeus

- Genre:

- Year:1967

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lytton Strachey: A Critical Biography: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Lytton Strachey: A Critical Biography" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lytton Strachey: A Critical Biography — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Lytton Strachey: A Critical Biography" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

www.headofzeus.com

The winter of 19634 was for me a crucial one. After two years work, and a further two years of waiting, I had had my first book published: a biography of Hugh Kingsmill, the novelist, biographer and critic. But two weeks after publication I was being threatened with an action for libel. The situation seemed perilous. My chief witness, Hesketh Pearson, who had encouraged me to write, suddenly died. I could muster other supporters, but they would hardly figure as star witnesses. There was Malcolm Muggeridge, who had contributed a marvellous introduction to my book, but who had elsewhere attacked the Queen and whose appearance in court was guaranteed to stir up violent antipathy in a jury. There was John Davenport, the critic, who at that time had chosen to wear a prejudicial black beard. And there was William Gerhardie, the distinguished novelist who had not actually published a novel for the last quarter of a century and who, besides denying that he spoke with a slight Russian intonation, would certainly turn up at the wrong courtroom or on the wrong day whatever precautions I took.

Altogether it was not a pleasant prospect. Yet my publisher, Martin Secker, who was nearing eighty, appeared to find the predicament wonderfully invigorating. It brought back to him, evidently, the good old fighting days of D.H. Lawrence, Norman Douglas and early Compton Mackenzie, all of whom he had published. While the old man seemed splendidly rejuvenated, I, still in my twenties, tottered towards a nervous senility. For nights on end I would start awake from dreadful courtroom scenes rhetorical but unavailing speeches from the dock to the dreary horror of early morning and the next batch of solicitors letters.

But out of this nightmare something had been born. The first of the sixteen publishers to whom I had submitted my Kingsmill manuscript was Heinemann. Fortunately it had fallen into the hands of James Michie, the poet and translator. He had liked it, had sent for me, and gently explained that were his firm to make a practice of bringing out books about almost unknown writers by totally unknown authors, it would very soon be bankrupt. However, I might become better known myself were I to choose a less obscure subject. Had I any ideas?

This was the opportunity for which I was looking. Kingsmill was said to be one of those biographers who had imitated Lytton Strachey and so helped to bring his literary reputation into disrepute. In order to demonstrate the injustice of this charge I had examined Stracheys books in some detail. To my surprise I found there was no literary biography of him. Was there not, I wondered, a need for such a book? James Michie agreed there was, and a contract was drawn up in which I undertook to make a re-evaluation of Stracheys place as a biographical historian. It would be about 70,000 words long and take me, I estimated, at least a year. A year later I had read everything published by and about Strachey, and I had produced an almost complete manuscript. But I had come to the conclusion that Strachey was one of those non-fiction writers whose work was so personal that it could be illuminated by some biographical commentary. It was impossible, from published sources, to reconstruct any worthwhile biography. As for unpublished sources, Clive Bell had sounded an ominous warning. Lytton could love, and perhaps he could hate, he had written.

To anyone who knew him well it is obvious that love and lust and that mysterious mixture of the two which is the hearts desire played in his life parts of which a biographer who fails to take account will make himself ridiculous. But I am not a biographer, nor can, nor should, a biography of Lytton Strachey be attempted for many years to come. It cannot be attempted till his letters have been published or any rate made accessible, and his letters should not be published till those he cared for and those who thought he cared for them are dead. Most of his papers luckily are in safe and scholarly hands.

This passage conjured up an almost impregnable stronghold into which I had to make a breach. But I had no doubt that within these fortifications lay solutions to many of the problems that my literary researches had raised. I knew none of the surviving members of the Bloomsbury Group, but I had been given the address of a certain Frances Partridge, a friend of Stracheys who had collaborated with him on the eight-volume edition of The Greville Memoirs. To write to her out of the blue and ask for assistance seemed as good a start as any.

I wrote. In her reply she explained that the person I should first get in touch with was James Strachey, Lyttons younger brother and literary executor. He was the key figure to any critical and biographical study such as I wanted to write. For if he were prepared to cooperate then she too would be ready to help me, and so also, she implied, would most of Lyttons other friends.

I met James Strachey a fortnight later. In the meantime various unnerving rumours concerning him had reached me. He was a psychoanalyst, who had been analysed by Freud, had subsequently worked for him in Vienna, and who, during the last twenty years, had been engaged on a monumental translation of the Masters works. This twenty-four volume edition, with its maze of additional footnotes and introductions, was said to be so fine as a work both of art and of scholarship that a distinguished German publishing house was endeavouring to have it retranslated back into German as their own Standard Edition. He was married to another psychoanalyst, Alix Sargant-Florence, author of The Unconscious Motives of War , a once brilliant cricket player and dancer at night clubs. Together, I was inaccurately informed by Osbert Sitwell, they had rented off the attics of their house to some unidentified people on whom they had practised their psychoanalytical experiments so that these wretched tenants no longer knew anything except the amount of their rent and the date it was due.

It was with some qualms that I approached their red-brick Edwardian house, set in the beech woods of Marlow Common. I arrived at mid-day, prepared for practically anything but not for what I found. Though it was frosty outside, the temperature within the house seemed set at a steady eighty degrees Fahrenheit. No windows were open and, to prevent the suspicion of a draught, cellophane curtains were drawn against them. There was an odour of disinfectant about the rooms. I felt I had entered a specially treated capsule where some rare variety of homo sapiens was being exquisitely preserved.

James Strachey was almost an exact replica of Freud himself, though with some traces of Lyttons physiognomy the slightly bulbous nose in particular. He wore a short white beard because, he told me, of the difficulty of shaving. He had had it now for some fifty years. He also wore spectacles, one lens of which was transparent, the other translucent. It was only later that I learnt he had overcome with extraordinary patience a series of eye operations that had threatened to put an end to his magnum opus. In a more subdued and somewhat less astringent form, he shared many of Lyttons qualities his humour, his depth and ambiguity of silence, his rational turn of mind, his shy emotionalism and something of his predisposition to vertigo. As he opened the front door to me, swaying slightly, murmuring something I failed to overhear, I wondered for a moment whether he might be ill. I extended a hand, a gesture which might be interpreted either as a formality or an offer of assistance. But he retreated, and I followed him in.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Lytton Strachey: A Critical Biography»

Look at similar books to Lytton Strachey: A Critical Biography. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Lytton Strachey: A Critical Biography and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.