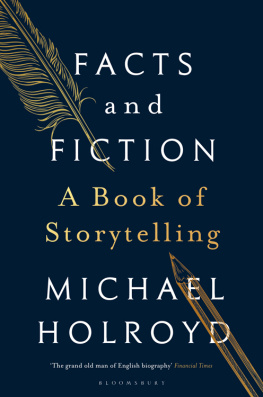

Michael Holroyd - Facts And Fiction; A Book Of Storytelling

Here you can read online Michael Holroyd - Facts And Fiction; A Book Of Storytelling full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Facts And Fiction; A Book Of Storytelling

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Facts And Fiction; A Book Of Storytelling: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Facts And Fiction; A Book Of Storytelling" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Michael Holroyd: author's other books

Who wrote Facts And Fiction; A Book Of Storytelling? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Facts And Fiction; A Book Of Storytelling — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Facts And Fiction; A Book Of Storytelling" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

FACTS AND FICTION

Non-Fiction

Hugh Kingsmill

Unreceived Opinions

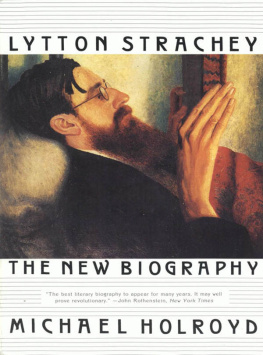

Lytton Strachey

Augustus John

Bernard Shaw

Basil Street Blues

Works on Paper

Mosaic

A Strange Eventful History

Ancestors in the Attic (two volumes)

A Book of Secrets

Fiction

A Dogs Life

As Editor

The Best of Hugh Kingsmill

Lytton Strachey By Himself

The Art of Augustus John (with Malcolm Easton)

The Genius of Shaw

The Shorter Strachey (with Paul Levy)

William Gerhardie: Gods Fifth Column (with Robert Skidelsky)

I do not know exactly how I chose the subjects for these essays and articles over the last twenty years. It is something of a mystery and I enjoy mysteries. One or two of them can be linked to minor characters in my biographies, and I came across others in the books of other writers. But most of them seem to have reached me accidentally. These were happy accidents and even happier when they found some magazine or newspaper that gently paid me for their publication long before they eventually elbowed themselves into this book. They appeared all over the place: in the Charleston Souvenir Programme, the London Magazine, the Folio Society, the Times Literary Supplement, the Guardian, the Financial Times, the Telegraph, the Spectator, New Statesman and Slightly Foxed. Almost all of them that appear in this volume were written during the twentieth century, but the earliest one was first published in 1979, beginning not with a birth but a death: the death of my grandfather or, as I saw it, his many deaths.

I am grateful for initial guidance from Caradoc King at United Agents and also the encouragement from the Bloomsbury team: the publishing director Michael Fishwick, Kate Quarry the copy-editor, Jasmine Horsey, the assistant editor, Francesca Sturiale in charge of production, the publicist Chloe Foster and Angelique Tran Van Sang who kept us all amiably in contact.

No one asked me to be a biographer. Quite the opposite. My grandfather hoped I might set off for India and make a career at the tea plantations there. He had been presented with some shares in one of the Assam tea companies by his father. He used these shares as if they were tickets that took him on a summer holiday, which he called following the business. What he really wanted was to go abroad without his family from time to time. I saw a photo of him in India once: he was smiling in a way I had never seem him smile at home. And he was encircled by rather bemused-looking planters.

Back at home he taught me the skills of making a proper cup of tea. It was not easy: how to hold the cup correctly; how to boil the water to an exact temperature and then how to engage the small spoons of tea with water at the right moment. Then there was the difficulty of preparing the milk and adding it. Sugar was never tolerated. Writing a biography was far easier than preparing a correct cup of tea or so it seemed to me. In the end I wrote a small biography of my grandfather and placed it in my autobiography.

Most people do not encourage members of their family to become biographers. There is no telling what trouble they will get into. If you write fiction, any member of your family who appears on the pages of your book will be hidden by a different name that prevents them being recognised. But biographers are always invading other peoples families uninvited, writing about the dead who cannot answer them and presenting what they have written to their subjects families and friends. Its no surprise we are not welcome.

I was fortunate in never being at a university, going instead to the public library for my education. In the library I found hundreds of possible subjects lined up in alphabetical order and waiting to be chosen. There they all were: Dickens, Shakespeare, Samuel Johnson, Hugh Kingsmill. Which one would you have chosen? I chose the last one. He seemed to have something the others didnt have: an absence of biographies about him (though he wrote some biographies himself all of them safely out of print). He was, I thought, an obvious choice.

I finished my biography of him within two years keeping alive doing odd jobs and writing reviews of other peoples biographies. Over the next two years I sent my typescript to sixteen publishers who sent it back to me with polite letters. They thanked me for sending it to them and implied that they would have very much liked to publish it, but unfortunately couldnt. They were sorry and so was I. Sorrow filled the air. But eventually it was taken by someone who had recently given up publishing: Martin Secker. He was, someone told me by way of explanation, almost blind. Mine was the last book he published in his life and he did so with a colleague. It was brought out in 1964 by the Unicorn Press and I was given a generous advance of 25. This came in useful when Kingsmills second wife objected to a couple of pages in which she appeared and I paid for the rewriting. This rare first edition revealed that it was the strange and mysterious quality of her silences which exerted so compelling a power. I wish she had been more silent with me.

I was gradually learning the complexities of biography, which was almost as difficult as my grandfathers tea making. My father, if asked, would say that I was a historian, which sounded more respectable. He could not see how I would make a financial career from writing and wished I had become a scientist. If I had a proper career I could, he said, write peoples lives on Sundays and, if absolutely necessary, on Saturdays too. What more could I need?

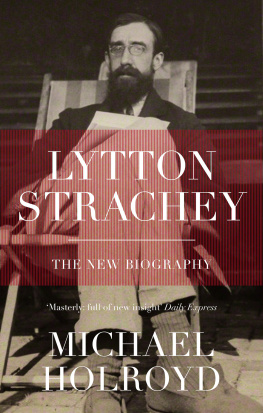

As it was, one of the publishers that had amiably turned down my Kingsmill suggested I should try someone else preferably someone not unknown but not yet written about. Such subjects are hard to find, I discovered, but eventually I came up with Lytton Strachey. He was a biographer without a biography. What could be better? Indeed he was so good a choice that I was given twice the 25 advance for my first biography. But since it took me seven years to complete the book, I had to renegotiate this part of my contract as many times as Britain negotiated joining and then leaving Europe.

In one of his essays the Bloomsbury art critic Clive Bell had written after Stracheys death in 1932 that it would be impossible to write his biography for a long time. It certainly took me a long time to write his life though that was not what Bell had in mind. In the early 1960s homosexuality was still illegal. It was brave of some of Stracheys friends to talk to me about this. Shall I be put in jail? one of them asked. Will I be allowed to watch cricket any more at Lords? asked another. It seems ridiculous now, and it was fortunate that the law changed shortly before my biography was published in 1967. Some of the most charming readers of the book were men who invited me to dinner but were disappointed.

What involved me most deeply was Stracheys extraordinary relationship with Dora Carrington. Though my biographies usually have a mans name on the title page, women take over many chapters. This was inevitably true with my next subject, the artist Augustus John. Walking along the streets of Chelsea in London he sometimes patted the heads of children in case, he explained, they are some of mine.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Facts And Fiction; A Book Of Storytelling»

Look at similar books to Facts And Fiction; A Book Of Storytelling. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Facts And Fiction; A Book Of Storytelling and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.