The list of people who helped me with the preparation of this biography in the 1960s has become a necrology, and I have not reproduced it again. But I would like to renew my thanks to Frances Partridge who has once more looked through my account of Lytton Stracheys later life and generously given me additional information.

The present edition has been written with the assistance of a number of institutions which appear in my bibliographical appendix. I am also indebted to Sally Brown, Jane Hill, Cathy Henderson, Robert Skidelsky, Frances Spalding, David Sutton, Winifred Thomson, Ann Thwaite; to Angelene Rackett of the Bank of England for advice about money conversions; and to the Courtauld Institute, the Bridgeman Art Library, the National Portrait Gallery, the Tate Gallery, Angelica Garnett and Lady Pansy Lamb for permission to reproduce illustrations.

The book has benefited from the care and house-style severities of my editor Alison Samuel. I am grateful to her and to Sarah Johnson who has found the time from her own writings to follow the twists and turns of my amalgamated typing and handwriting, and transfer it all on to disc.

MICHAEL HOLROYD

Porlock Weir, February 1994

By the same author

NONFICTION

Hugh Kingsmill

Unreceived Opinions

Augustus John

Bernard Shaw

Basil Street Blues

Works on Paper

Mosaic

FICTION

A Dogs Life

EDITOR

The Best of Hugh Kingsmill

Lytton Strachey by Himself

The Art of Augustus John

with Malcolm Easton

The Genius of Shaw

with Paul Levy

William Gerhardies Gods Fifth Column

with Robert Skidelsky

Essays by Divers Hands

New Series: Volume XLII

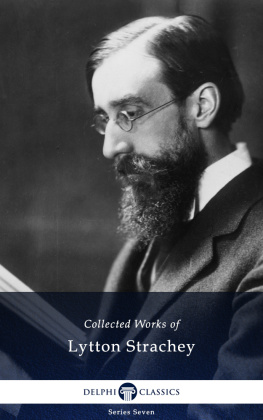

When I was writing this biography in the 1960s almost all the Strachey papers were privately owned. Apart from working at Lords Wood, James and Alix Stracheys home, and at the Strachey family home, 51 Gordon Square, where I met Philippa (Pippa) Strachey, I went to the houses of Lyttons friends and their families: reading through the correspondence to David Garnett at Hilton Hall; to Ottoline Morrell with her daughter Julian Vinogradoff in Gower Street; to Barbara Bagenal at her home in Rye. Most of the people I was writing about were still alive. I saw Noel Carrington at Lambourne, Duncan Grant at Charleston, Bertrand Russell in Wales, E.M. Forster and Sir John Sheppard at Cambridge, Sebastian Sprott in Nottingham and, in London, Boris Anrep, Clive Bell, Bonamy (but not Valentine) Dobre, Mary Hutchinson, Rosamond Lehmann, Osbert Sitwell, Arthur Waley, Leonard Woolf. Roger Senhouse and Dadie Rylands lent me Stracheys letters to them. Gerald Brenan and Frances Partridge the latter at some emotional cost copied out pages of diaries and correspondence for me.

There was one manuscript anomaly. In Other People: Diaries September 1963December 1966 (1993), Frances Partridge records that Nol Annan, then Provost of Kings College, Cambridge, spoke to her in 1966 about the Lytton Strachey and Maynard Keynes correspondence which was at Kings under an embargo though she herself remembered hearing it read one icy weekend at Charleston, and only realized just in time that this was a deadly secret. In her diary entry for 22 January 1966, she wrote: Holroyd dined with me two nights ago and went through the Ham Spray albums; Im pretty sure he told me then that he also had read the above letters, but the Provost of Kings had not. I did ask Annan if Holroyd saw them when he came to Kings and he said, Oh no. Ive not seen them myself.

This strange situation arose out of a compromise that had been reached between Geoffrey Keynes and James Strachey. Geoffrey Keynes wanted the correspondence destroyed and James Strachey wanted it published. Eventually they agreed to deposit the letters at Kings College on the understanding that nothing should be read until 1986. I saw them together in the early 1960s and I thought I detected in each of them a determination to outlive the other so that his own solution might prevail. In case of accidents, however, and before the deposit of manuscripts was accomplished, James Strachey had in 1948 made a secret microfilm of it all (to which he added Duncan Grants letters to Lytton). It may be that the Charleston reading was from the originals before they were sent to Kings. I worked from the microfilms, seating myself in my room before that huge black instrument I had hired. But I soon grew worried by the awkwardness of publishing extracts from a collection that was being so sternly guarded. Before my book appeared, I therefore went to see the legendary librarian at Kings, A.N.L. Munby, and explained the position. To my surprise he took it as a great joke which added to the fun of a librarians career.

In 1967, a few months before my biography was published, James Strachey died. In the Bloomsbury style he had made many derogatory comments about my work to others, but this may have assisted him in dealing generously with me. I can see now that I must have been a disappointment to him. But he was determined to make the best of a bad job. Over the five years I knew him I had moved from apprehension and incomprehension, through a sense of gratitude, into a feeling of guarded affection for him. In so far as he began to feel some exasperated goodwill towards me, this was I think shared by his widow Alix Strachey.

Alix now became Lytton Stracheys copyright holder, and it was she who enabled me to edit the autobiographical Lytton Strachey by Himself in 1971. One episode connected with that book will illustrate her tolerance and generosity. She lent two Carrington portraits of Lytton to my publishers who wanted to use one or other of them as a design for the jacket. These pictures were afterwards to be taken by the publishers to the Upper Grosvenor Galleries, some five or six hundred yards away, for the first exhibition of Carringtons work. But when the pictures had been photographed, the publishers placing them by the front door for a couple of minutes while a van was backed up, both of them were in those couple of minutes stolen and, despite a reward being offered, they were never recovered. I felt mortified. But Alix Strachey took this rather frightful news over those wretched stolen pictures with philosophical mildness, never showing any sense of grievance or voicing any complaint to me though there were some wild enough rumours elsewhere. I suppose this sort of thing is going on everywhere all the time, she wrote (26 September 1970).

In 1972 Alix Strachey created the Strachey Trust, a registered charity the main purpose of which was legally defined as the searching out by all available means of manuscripts and the establishment by mechanical processes or otherwise and the maintenance for the benefit of the public of a register of manuscripts so discovered being a register indicating the nature of the manuscript and where it is kept. To this Trust, Alix gave all Lyttons papers, and, on her death in 1973, she also willed to the Trust Lyttons literary copyrights together with her own and those of James Strachey.

Alix had two pet fears. The first was of dying in the gutter and the second was of being led away in chains for doing something wrong about the Income Tax. The creation of a Charitable Trust, and the making of a publishing programme with her retaining all copyright income during her lifetime, went some way to warming her cold feet.

Her posthumous intention was to increase the accessibility of manuscript collections to scholars. The founders and original trustees of the Trust were myself, G.E. Moores biographer Paul Levy, and the historian and translator from the French Lucy Norton, sister of Harry Norton to whom

Next page