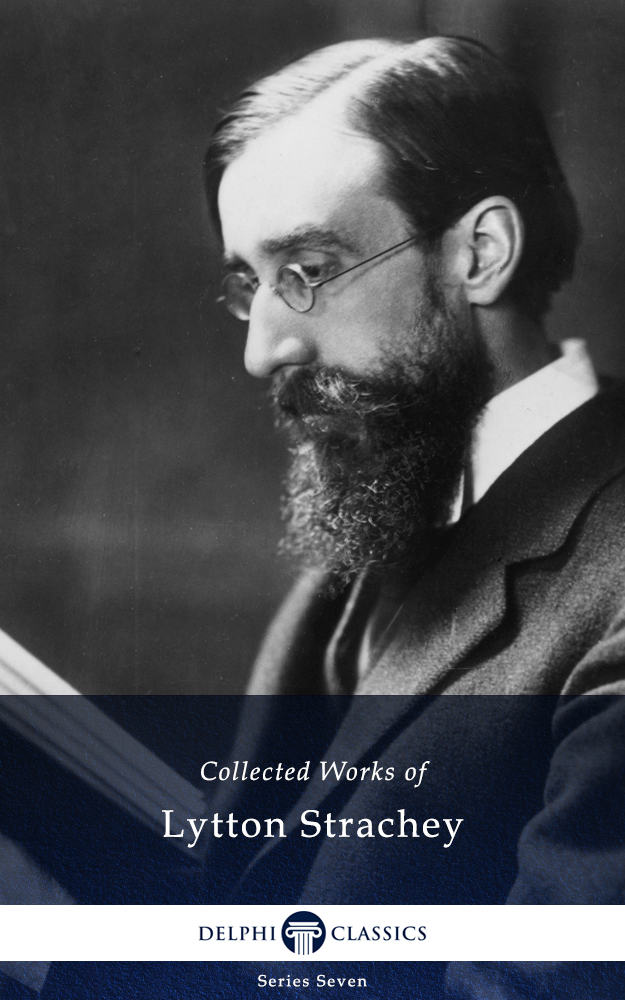

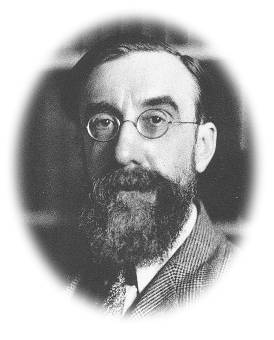

The Collected Works of

LYTTON STRACHEY

(18801932)

Contents

Delphi Classics 2016

Version 1

The Collected Works of

LYTTON STRACHEY

By Delphi Classics, 2016

COPYRIGHT

Collected Works of Lytton Strachey

First published in the United Kingdom in 2016 by Delphi Classics.

Delphi Classics, 2016.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 9781786560575

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: sales@delphiclassics.com

www.delphiclassics.com

Parts Edition Now Available!

Love reading Lytton Strachey ?

Did you know you can now purchase the Delphi Classics Parts Edition of this author and enjoy all the novels, plays, non-fiction books and other works as individual eBooks? Now, you can select and read individual novels etc. and know precisely where you are in an eBook. You will also be able to manage space better on your eReading devices.

The Parts Edition is only available direct from the Delphi Classics website.

For more information about this exciting new format and to try free Parts Edition downloads , please visit this link .

The Books

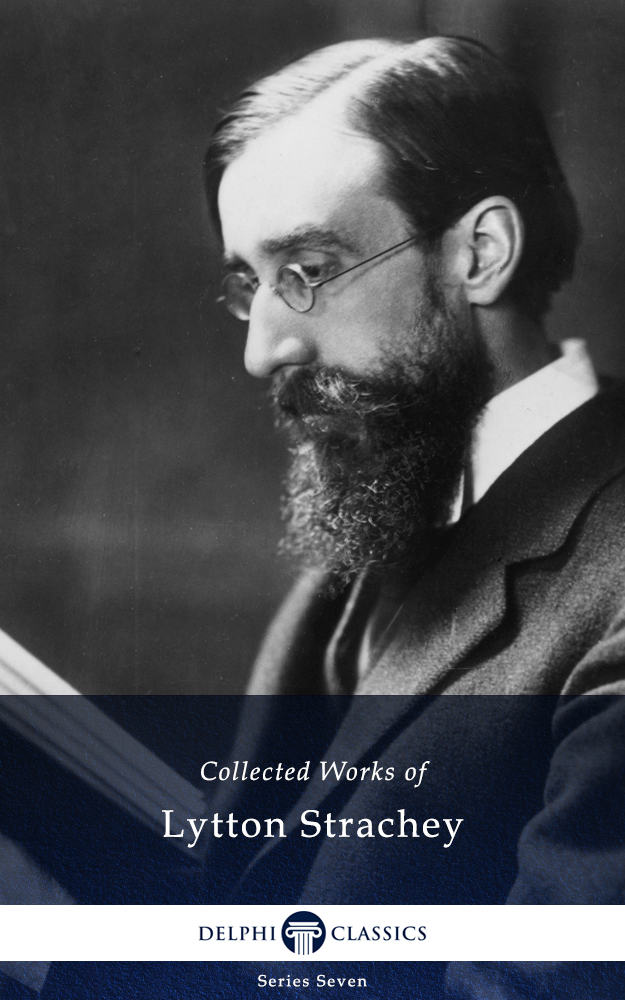

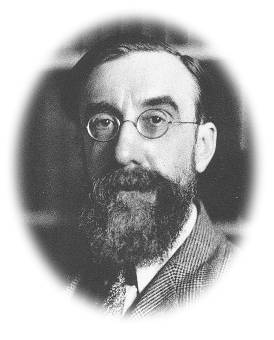

Clapham Common, south London Lytton Strachey was born in Stowey House, Clapham Common in 1880.

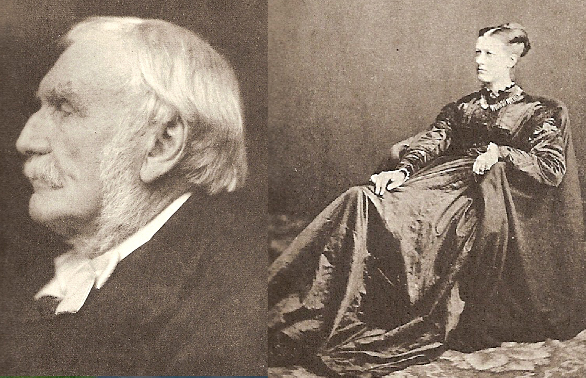

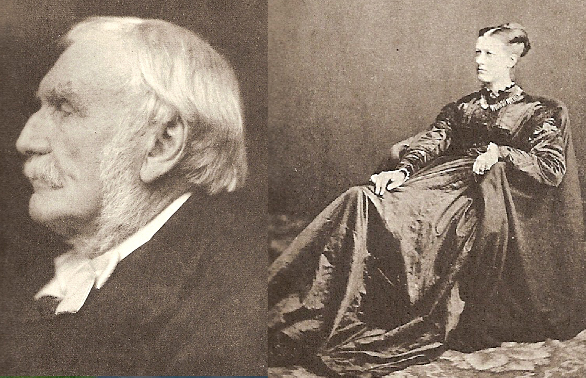

Stracheys parents: the author was the fifth son and the eleventh child of Lieutenant General Sir Richard Strachey, an officer in the British colonial armed forces, and his second wife, Jane Grant, who became a leading supporter of the womens suffrage movement.

INTRODUCTION FOR A SIMPLE STORY by E. Inchbald

INTRODUCTION

A Simple Story is one of those books which, for some reason or other, have failed to come down to us, as they deserved, along the current of time, but have drifted into a literary backwater where only the professional critic or the curious discoverer can find them out. The iniquity of oblivion blindly scattereth her poppy; and nowhere more blindly than in the republic of letters. If we were to inquire how it has happened that the true value of Mrs. Inchbalds achievement has passed out of general recognition, perhaps the answer to our question would be found to lie in the extreme difficulty with which the mass of readers detect and appreciate mere quality in literature. Their judgment is swayed by a hundred side-considerations which have nothing to do with art, but happen easily to impress the imagination, or to fit in with the fashion of the hour. The reputation of Mrs. Inchbalds contemporary, Fanny Burney, is a case in point. Every one has heard of Fanny Burneys novels, and Evelina is still widely read. Yet it is impossible to doubt that, so far as quality alone is concerned, Evelina deserves to be ranked considerably below A Simple Story . But its writer was the familiar friend of the greatest spirits of her age; she was the author of one of the best of diaries; and her work was immediately and immensely popular. Thus it has happened that the name of Fanny Burney has maintained its place upon the roll of English novelists, while that of Mrs. Inchbald is forgotten.

But the obscurity of Mrs. Inchbalds career has not, of course, been the only reason for the neglect of her work. The merits of A Simple Story are of a kind peculiarly calculated to escape the notice of a generation of readers brought up on the fiction of the nineteenth century. That fiction, infinitely various as it is, possesses at least one characteristic common to the whole of it a breadth of outlook upon life, which can be paralleled by no other body of literature in the world save that of the Elizabethans. But the comprehensiveness of view shared by Dickens and Tolstoy, by Balzac and George Eliot, finds no place in Mrs. Inchbalds work. Compared with A Simple Story even the narrow canvases of Jane Austen seem spacious pictures of diversified life. Mrs. Inchbalds novel is not concerned with the world at large, or with any section of society, hardly even with the family; its subject is a group of two or three individuals whose interaction forms the whole business of the book. There is no local colour in it, no complexity of detail nor violence of contrast; the atmosphere is vague and neutral, the action passes among ill-defined sitting-rooms, and the most poignant scene in the story takes place upon a staircase which has never been described. Thus the reader of modern novels is inevitably struck, in A Simple Story , by a sense of emptiness and thinness, which may well blind him to high intrinsic merits. The spirit of the eighteenth century is certainly present in the book, but it is the eighteenth century of France rather than of England. Mrs. Inchbald no doubt owed much to Richardson; her view of life is the indoor sentimental view of the great author of Clarissa ; but her treatment of it has very little in common with his method of microscopic analysis and vast accumulation. If she belongs to any school, it is among the followers of the French classical tradition that she must be placed. A Simple Story is, in its small way, a descendant of the Tragedies of Racine; and Miss Milner may claim relationship with Madame de Clves.

Besides her narrowness of vision, Mrs. Inchbald possesses another quality, no less characteristic of her French predecessors, and no less rare among the novelists of England. She is essentially a stylist a writer whose whole conception of her art is dominated by stylistic intention. Her style, it is true, is on the whole poor; it is often heavy and pompous, sometimes clumsy and indistinct; compared with the style of such a master as Thackeray it sinks at once into insignificance. But the interest of her style does not lie in its intrinsic merit so much as in the use to which she puts it. Thackerays style is mere ornament, existing independently of what he has to say; Mrs. Inchbalds is part and parcel of her matter. The result is that when, in moments of inspiration, she rises to the height of her opportunity, when, mastering her material, she invests her expression with the whole intensity of her feeling and her thought, then she achieves effects of the rarest beauty effects of a kind for which one may search through Thackeray in vain. The most triumphant of these passages is the scene on the staircase of Elmwood House a passage which would be spoilt by quotation and which no one who has ever read it could forget. But the same quality is to be found throughout her work. Oh, Miss Woodley! exclaims Miss Milner, forced at last to confess to her friend what she feels towards Dorriforth, I love him with all the passion of a mistress, and with all the tenderness of a wife. No young lady, even in the eighteenth century, ever gave utterance to such a sentence as that. It is the sentence, not of a speaker, but of a writer; and yet, for that very reason, it is delightful, and comes to us charged with a curious sense of emotion, which is none the less real for its elaboration. In Nature and Art , Mrs. Inchbalds second novel, the climax of the story is told in a series of short paragraphs, which, for bitterness and concentration of style, are almost reminiscent of Stendhal:

Next page