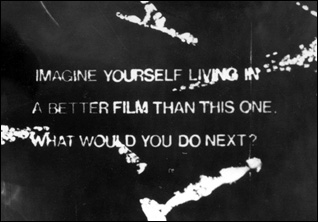

Everybody loves the movies. But what of movies made about the colour blue, or an isolated mountain range, or a man grown so thin the world floats through his perfect transparency? You know what would be really great to make a two-hour movie about Taylor Meads ass. So said Andy Warhol, the most notorious fringe filmer of them all. Welcome to the strange and wonderful microverse of fringe cinema, where the only rules left unbroken are the ones that have been forgotten. Long before MTV, these artists were bending light to make a strange, first-person possible.

This new edition features never-before-heard raps from Ellie Epp, Ann Marie Fleming, Chris Gallagher, Anna Gronau, Rick Hancox, John Kneller, Deirdre Logue, David Rimmer and Kika Thorne. They join fellow fringers Mike Snow, Carl Brown, Patricia Gruben, Barbara Sternberg, Al Razutis, Penelope Buitenhuis, Fumiko Kiyooka, Peter Lipskis, Wrik Mead, Annette Mangaard, Steve Sanguedolce, Gary Popovich, Philip Hoffman, Garin Torossian, Richard Kerr, and Mike Cartmell.

Twenty-five interviews with Canadas finest underdogs lay it all down like a road, ready to take you through the vanishing point of personality. This is cinema made one frame at a time, truth twenty-four times a second, as one wag would have it, a cinema that is earned and lived before being bigged up into the projector light. These lives have each developed an eccentric attention, a way of seeing the world that is able to transform something you walk past every day into something strange and terrifying. For any who wondered what lay beyond the McCinemas, the monotone of multiplex occupations, here are the stars of a different kind of night.

INSIDE THE

PLEASURE DOME

FRINGE FILM

IN CANADA

MIKE HOOLBOOM

Text copyright 2001 Michael Hoolboom

First edition 1997

Second edition 2001

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Hoolboom, Michael

Inside the pleasure dome: fringe film in Canada

Rev. ed.

ISBN 1-55245-099-6

This epub edition published in 2010. Electronic ISBN 978 1 77056 115 1.

1. Experimental films Canada History and criticism.

2. Motion picture producers and directors Canada Interviews.

I. Title. II. Title: Fringe film in Canada

PN1995.9.E96H64 2001 791.430971 C2001-903087-8

Front cover photo: Kika Thorne

Back cover photo: Carl Brown

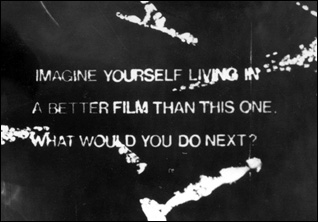

White Museum and Imagine Yourself photos: Mike Hoolboom

Published with the assistance of the Canada Council for the

Arts and the Ontario Arts Council.

Manufactured in Canada by Coach House Printing.

Revised Edition 2001

This book would not have been possible without the contributions of so many, but most especially: Karen Hanson, Marc Glassman, Alex Mackenzie, Darren Wershler-Henry, Alana Wilcox, Jason McBride, Rick/Simon, Ian McInnis, Stan Bevington, Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, Richard Holden, the Writing and Publishing Division of the Canada Council, Canada Council Media Arts, the Literature Office of the Ontario Arts Council, and all of the filmmakers who gave generously of their time, their insights, and their ideals.

CONTENTS

by ATOM EGOYAN

MICHAEL SNOW

CARL BROWN

PATRICIA GRUBEN

Sifted Evidence

BARBARA STERNBERG

Transitions

AL RAZUTIS

Three Decades of Rage

PENELOPE BUITENHUIS

Guns, Girls and Guerrillas

FUMIKO KIYOOKA

The Place with Many Rooms Is the Body

PETER LIPSKIS

I Was a Teenage Personality Crisis!

WRIK MEAD

Out of the Closet

ANNETTE MANGAARD

Her Soil is Gold

STEVE SANGUEDOLCE

Sex, Madness and the Church

GARY POPOVICH

Lies My Father Told Me

PHILIP HOFFMAN

Pictures of Home

GARIN TOROSSIAN

Girl From Moush

RICHARD KERR

Last Days of Living

MIKE CARTMELL

Watching Death at Work

RICK HANCOX

Theres a Future in Our Past

DEIRDRE LOGUE

Transformer Toy

ANN MARIE FLEMING

Queen of Disaster

CHRIS GALLAGHER

Terminal City

DAVID RIMMER

Fringe Royalty

ELLIE EPP

Notes in Origin

JOHN KNELLER

The Church of Film

ANNA GRONAU

The Dead Are Not Powerless

KIKA THORNE

What Is To Be Done?

FOREWORD

Why am I writing the foreword to this book? What does my sensibility and creative orientation have to do with the work discussed here? Where does my world (commercially conceived and distributed feature films) meet the visions and ideas of the experimental filmmakers discussed in this collection?

The answer might be in the imaginary audience we both share. Ive been deeply inspired by artists like Michael Snow, David Rimmer, Phil Hoffman, Peter Mettler, Michael Hoolboom, Barbara Sternberg, and Bruce Elder not simply because of the extraordinary quality of their work, but also, and perhaps more profoundly, because of the ceaselessly curious and completely trusting nature of the audience theyve had to imagine for their creative efforts.

These filmmakers taught me that there is nothing more exhilarating than to feel self-conscious in front of a screen. The viewer did not have to lose themselves into an image, but could actually observe it, and create a dialogue about that process. This dialogue could be meditative, amusing, and provocative. By watching these films, I learned how to respect and indulge the intelligence of my audience.

We dream in moving pictures. Every night, images are conjured in our minds, induced by mysterious and primal needs for sub-conscious expression. Ive always found it fascinating that the serious attempt to articulate and find meaning to these dreams paralleled the discovery and development of cinema. Its also fascinating that the essential grammar of mainstream cinema has remained relatively unchanged since the art forms inception. From the first films, it became evident that there were certain places you could put a camera, and certain places where you couldnt.

No other art form has been so immediately and comprehensively bound by such an orthodox and rigid system.

Why did this happen? Was it because of a latent terror that seized us when we discovered a medium so close to our dreams? or, more to the point, is the traditional grammar of cinema a direct expression of how we dream? Do we dream in multi-angle coverage, with static masters, close-ups, tracking shots, and pans? Do we never cross the magical axis, except when we wake out of our sleep in terror? Is this why the language of early cinema came so quickly because weve been playing it inside our heads forever?

I ask these questions because the films discussed in this book come from a different perspective. They are truly revolutionary; not simply because they defy conventional rules of industrial cinema, but because they confront the very nature of what we need to see. We are driven as much by narrative as by impulse, yet mainstream cinema is almost completely concerned with giving expression to ego-based storytelling.

Fringe films are id-based. They address, liberated from the moderating influence of narrative, our purest sense of impulse the way we see. To treat these films as marginal is to marginalize some integral part of ourselves.

Atom Egoyan

Next page