Sir Julian Huxley M.A. D.Sc. F.R.S.

John Gilmour M.A. V.M.H.

Margaret Davies D.Sc.

Kenneth Mellanby C.B.E. Sc.D.

PHOTOGRAPHIC EDITOR:

Eric Hosking F.R.P.S.

The aim of this series is to interest the general reader in the wild life of Britain by recapturing the inquiring spirit of the old naturalists. The editors believe that the natural pride of the British public in the native fauna and flora, to which must be added concern for their conservation, is best fostered by maintaining a high standard of accuracy combined with clarity of exposition presenting the results of modern scientific research.

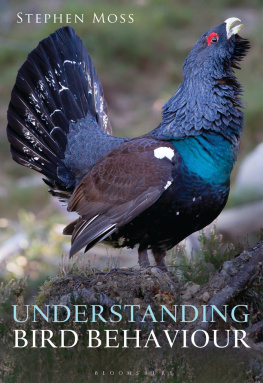

Several of the New Naturalist special monograph volumes have dealt very successfully with single species of birds, including the ubiquitous House Sparrow and the Wood Pigeon, as well as the more uncommon Redstart, Yellow Wagtail and Hawfinch. We have now, for the first time, been able to produce, in the main New Naturalist series, a volume dealing with a whole group of birds. The eighteen European finches described here include some of the most familiar British birds. Thus the Chaffinch is one of the very commonest, having adapted its mode of life to man-made habitats so that it is well known to every suburban gardener. The Bullfinch is detested as a pest by the fruit farmer, though its handsome appearance endears it to others. The Greenfinch, the Linnet and the Goldfinch are familiar even to the relatively unobservant countryman. Other birds included here range from the Hawfinch, not uncommon locally but seldom seen in many areas, to occasional migrants such as the Scarlet Rosefinch which most of us never expect to be lucky enough to see at all.

Dr Ian Newton shows himself to be the ideal author to pioneer this new development. He combines the rigorous standards of the professional scientist with the fresh approach of the dedicated field observer. He knows all the birds described from personal experience. However, no one scientist could cover the whole of such a wide subject completely, and Dr Newton is sufficiently familiar with the work of others and with the international literature to be able to deal with his vast subject in a critical manner. He has himself contributed substantially to the literature on finches, with many important scientific papers on the Bullfinch and other species. His own work includes both intensive field studies and laboratory experiments to illuminate observations made under natural conditions.

The thing which readers will find most exciting in this book is the way Dr Newton so frequently draws on his own observations to illuminate his text. This he does in such a modest tone that we do not immediately realise what enormous efforts have been expended to produce the relevant information. Thus we are told that, when studying the Linnet, repeated visits were paid to 62 different broods, and full records were made on each occasion. How many of us in a life time of observation have even found anything like 62 Linnet nests, without having made any serious observations on any substantial number of them?

The finches are shown by Dr Newton to be a fascinating group of birds. The whole of their ecology is described, not by a boring catalogue of facts, but in such a way that their reactions to different factors in the environment are discussed, giving a dynamic picture of their relationships to the whole countryside. Obviously full explanations of the successes and failures of all the species cannot be given, but the comparisons between these closely-related birds does begin to show us the way in which we may ultimately understand these processes.

It is impossible today to include the wide range of coloured photographs used in some of the earlier New Naturalist volumes. However, we still endeavour to include illustrations of a high standard. Here, instead of having any colour photographs, we have produced four pages of the superb paintings by Hermann Heinzel, showing all the distinct plumages of the birds considered in the text. These, we believe, are not only of real artistic merit, but also give more accurate representations than could be obtained by any other method.

We believe that Ian Newtons Finches will be warmly welcomed by all those interested in our countryside. Ornithologists and birdwatchers will learn much that is fresh about their particular specialities, and others will increase their general understanding of the interdependence of all forms of wildlife on the changing environment.

THIS book is intended for anyone who wants to know more about the European finches, but who has neither the time nor inclination to search through scientific periodicals. Technical terms are kept to a minimum. The first three chapters are mainly factual, and set out to summarise the main characteristics, habits and distribution of the individual species. The remaining fourteen chapters discuss particular aspects of finch-biology, such as feeding, moult or migration, on a comparative basis for the group as a whole. These chapters are unashamedly biased towards those problems which have caught my own interest. Thus, eight are based almost entirely on my own research, while others aim to draw together both personal observations and a scattered literature, and in this sense the resulting syntheses are new. One result of this form of presentation is that the information on each species is scattered through the book, though the index, I hope, will take care of this.

To compile the book, I have searched the literature to 1970 (but had to be highly selective), and the ringing recoveries from 1955 to 1966, or in some species to 1969. Also, to illustrate certain points, I have not hesitated to refer to related finches in other parts of the world, if these species have been studied in more detail than the European ones. For the latter, the nomenclature follows Vaurie (1959).

My own research was carried out mainly during six years at the Edward Grey Institute, in Oxford, and I owe a great debt to the director, Dr David Lack, for stimulation and advice, and for kindly and helpful criticism of parts of the book in draft. While in Oxford, most of my field-work was carried out on Wytham Estate, and I am grateful to the University for permission to work there. I would also like to thank Drs R. S. Bailey, P. R. Evans, D. Jenkins, A. D. Middleton, D. Nethersole-Thompson, C. M. Perrins and P. Ward for helpful comments on the early drafts of particular chapters; Miss J. Coldrey and Dr J. Pinowski for bibliographical help; J. Cudworth, A. Frudd, C. J. Mead, H. Ostroznik, R. S. Scott, and J. G. Young for allowing me to use their unpublished data or for help in other ways; and the British Trust for Ornithology for allowing me to consult their ringing data. Finally, I would like to thank Hermann Heinzel and Robert Gillmor for their delightful illustrations. The former is responsible for the colour plates and figures 3, 8 and 17; and the latter for the pleasing and accurate representations of various displays and postures. Figure 46 was taken from Guy Mountforts (1956) book on the Hawfinch, and was drawn by Keith Shackleton.

I. NEWTON

To most people, the word finch implies a small, seed-eating bird with a stout bill. But in one part of the world or another, the same word has been applied to at least eleven different groups of birds of varying degrees of affinity, namely the sub-families Fringillinae (chaffinches and allies), Carduelinae (goldfinches and allies), Emberizinae (buntings), Tanagrinae (tanagers), Geospizinae (Galpagos finches), Pyrrhuloxinae (cardinal-grosbeaks), Bubalornithinae (buffalo-weavers), Estrildinae (weaver-finches), Viduinae (whydahs), Ploceinae (weavers), and Passerinae (sparrows). All these birds have the same specialisations for dealing with hard seeds: heavy, conical bills, strong skulls, large jaw muscles and powerful gizzards. Yet they differ so much in the other details of their anatomy and their behaviour, that they are without doubt derived from several ancestral stocks. They provide an example of convergent evolution of unrelated animals growing to look like one another because they have the same way of life.