Henry Iles (first and last page, p.).

Thanks

I met some wonderful people in the course of writing this book; their names are mentioned throughout and to them all I owe a debt of thanks. Some, Im happy to say, have become friends and theyve been kind enough to save me from myself. Mistakes and misapprehensions have been corrected, knowledge generously shared, and my stupidities tactfully brought to my attention before they were set in print.

To Tim Dee, especially for the birds; to Donald Wilkie, skipper of the Annag; to Dawn Kemp, museum curator at the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh; to Sarah Money of the RSPB, to Robin and Caroline Guthrie, Pete Barrass and Don Paterson, many thanks. Colette Bryce shared birds and basking shark enthusiasms, and Krys Hawryszczuk kept hauling me out into the hills, especially during the nappy years.

Things archaeological were explained to me by Steve Watt of Historic Scotland, the staff at Maes Howe, and Dr Simon Gilmour at the Royal Commision on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.

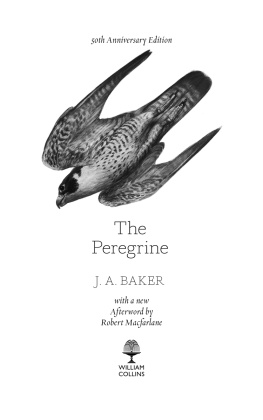

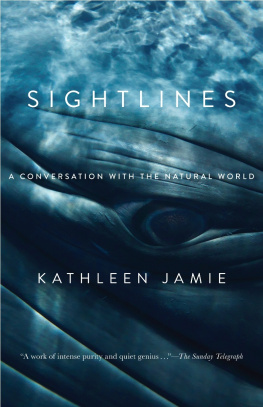

Peter Straus and Mary Mount saw the potential in this book from the start. BBC Radio 3 and the editors of the London Review of Books and the Dublin Review were good enough to publish parts en route. Peter Dyer and Henry Iles turned a manuscript into a thing of beauty.

Nat Jansz is a gifted editor: everything was discussed with her, often while walking on Hampstead Heath (those parakeets!). I thank her and Mark Ellingham for their hospitality, commitment and vision.

Finally, Id like to thank Phil Butler for his continuing gifts of time and space. It was Phil who gave me my first binoculars and encouraged me to buy a mountain bike. To him, and to Duncan and Freya, my love and gratitude.

They did the deed of darkness in their own mid-light

JAMES WRIGHT

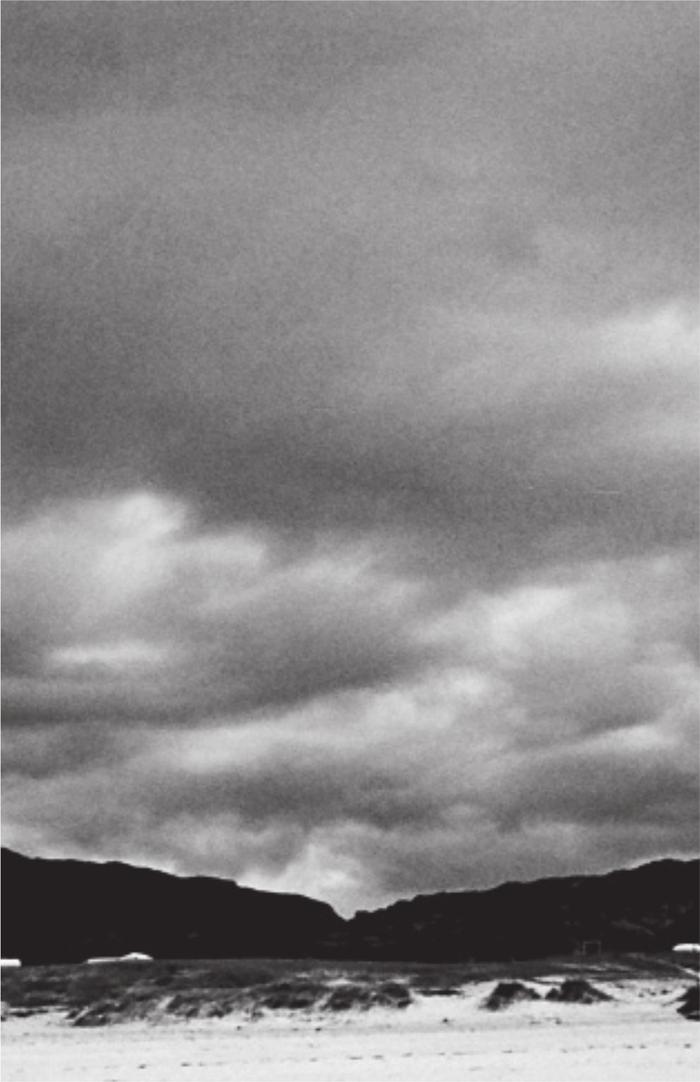

Mid-December, the still point of the turning year. It was eight in the morning and Venus was hanging like a wreckers light above the Black Craig. The hill itself seen from our kitchen window was still in silhouette, though the sky was lightening into a pale yellow-grey. It was a weakling light, stealing into the world like a thief through a window someone forgot to close.

The talk was all of Christmas shopping and kids parties. Quietly, though, like a coded message, an invitation arrived to a meal to celebrate the winter solstice. Only six people would be there, and no electric light.

That afternoon it was Saturday we took the kids to the pantomime. This year it was The Snow Queen. She was coldly glittery, and swirled around the stage in a platinum cloak with her comic entourage of ravens and spiders. The heroes were a boy and a brave, north-travelling girl. At one point the Snow Queen, in her silver sledge, stormed off stage left, and had she kept going, putting a girdle round the earth, shed have been following the 56th parallel. Up the Nethergate, out of Dundee, across Scotland, away over the North Atlantic, shed have made landfall over Labrador, swooped over Hudsons Bay, and have glittered like snowfall somewhere in southern Alaska. Crossing the Bering Sea, then the Sea of Okhotsk, shed have streaked on through central Moscow, in time, if she really got a move on, to enter stage right for her next line. Of course, we have no realm of snow here, none of the complete Arctic darkness. Nonetheless, when it came time for the Snow Queen to be vanquished for another year, to melt down through a trapdoor leaving only her puddled cloak, everyone was cheered. Before she went, however, the ascendant Sun God kissed the Snow Queen in a quick, knowing, grown-up complicity. I liked that bit.

I like the precise gestures of the sun, at this time of year. When it eventually rises above the hill it shines directly into our small kitchen window. A beam crosses the table and illuminates the hall beyond. In barely an hour, though, the sun sinks again below the hill, south-southeast , leaving a couple of hours of dwindling half-light . Everything we imagine doing, this time of year, we imagine doing in the dark.

I imagined travelling into the dark. Northward so it got darker as I went. Id a notion to sail by night, to enter into the dark for the love of its textures and wild intimacy . I had been asking around among literary people, readers of books, for instances of dark as natural phenomenon , rather than as a cover for all thats wicked, but could find few. It seems to me that our cherished metaphor of darkness is wearing out. The darkness through which might shine the Beacon of Hope. Isaiahs dark: The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light: they that dwell in the land of the shadow of death, upon them hath the light shined.

Pity the dark: were so concerned to overcome and banish it, its crammed full of all thats devilish, like some grim cupboard under the stair. But dark is good. We are conceived and carried in the darkness, are we not? When my son was born, a midwinter child, he cried pitifully at the wards lights, and only settled to sleep when he was laid in a big pram with a black hood under a black umbrella . Our vocabulary ebbs with the daylight, closes down with the cones of our retinas. I mean, I looked up darkness on the Web and was offered Christian ministries offering to lead me to salvation. And there is always death. We say death is darkness; and darkness death.

In Aberdeen, although it was not yet five oclock, the harbour lights were lit against the night sky. Ships were berthed right up against the street, and to reach the Orkney and Shetland ferry I had to walk under their massive prows. The ferry Hrossa was berthed among other ships, and though the Hrossa the Norse name for Orkney looked like a toppled office block, and was therefore a ferry, these other vessels were inexplicable mysteries to me, containers of purpose and might. Some carried huge yellow winches, others supported complex and insect-like antennae. The ships were named for strength and warriors, Scots and Norse: the HighlandPatriot, the Tor Viking. I boarded the ferry and went at once out on deck, although it was cold, and leaned over the rail. There was the Solar Prince (was it not he whod kissed the Snow Queen?) and, berthed beside it, the EddaFrigg.

The Edda Frigg was in the process of putting out. Where she was bound, what her purpose was, I had no idea, but it pleased me that I knew what the name meant: Edda the great Icelandic mythological poems. Frigg: Norse goddess, wife of one-eyed Odin. Off she went, the Queen of the Heavens, taking a long moment to pass, first the prow, then the low deck, then the super-structure , stirring the dirty dock water as she went.

Then it was our turn to edge out past other ships. Aberdeens streetlights, spires and illuminated clock-towers began to recede, and there was the moon itself, above the town. I was shivering now. A sudden flock of seagulls glittered under the harbour lights. Little scenes slipped by: two men hanging on the hook of a crane; stacks of ships containers; a sudden siren wailing, a line of parked-up lorries; the hammering of metal on metal. We inched past the red-hulled

![Kathleen Jamie [Kathleen Jamie] - Among Muslims](/uploads/posts/book/141349/thumbs/kathleen-jamie-kathleen-jamie-among-muslims.jpg)