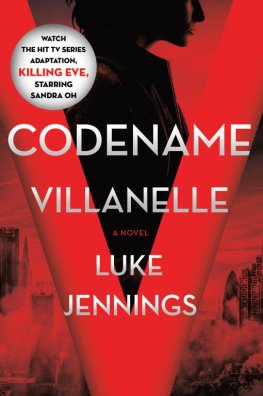

First published in hardback and export and airside trade paperback in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright Luke Jennings 2010

The moral right of Luke Jennings to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The author and publisher would gratefully like to acknowledge the following for permission to quote from copyrighted material: Burnt Norton from Four Quartets in Collected Poems 19091962 by T.S. Eliot, T.S. Eliot 1944, reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber for the author; The Pike in Collected Poems of Ted Hughes by Ted Hughes, Ted Hughes 1960, reproduced by permission of Faber & Faber for the author; A River Runs Through It by Norman McLean, 1976 by The University of Chicago, reproduced by permission of The University of Chicago Press.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

First eBook Edition: January 2010

ISBN: 978-1-848-87748-1

To Nicky, Basil, Rafe and Laura, as always

BY CLOSING TIME THERES NOT MUCH TRAFFIC GOING PAST the Kings Cross goods yards; perhaps its too late at night, or too close to Christmas. You can hear the distant rumble of the cars on the Euston Road, but in the yards its quiet. And very cold.

To get to the canal you have to duck underneath an advertising hoarding and push open an iron gate; although this used to be padlocked, someones taken a pair of bolt-cutters to it and now it just needs a good shove. Beyond it theres a railway maintenance supply area piled with concrete railway sleepers, rusted steel reinforcing rods and rectangles of welded wire mesh. Overlooking this are two low sheds. A pyramid of ceramic powerline insulators stands outside one of these and beside it a couple of figures are bowed over a flickering lighter. The tiny flame dies as I pass and then rekindles. There may be other people that I cant see. Some of the yard is lit by the sodium glare of the lights on Goods Way, whilst most of it is black shadow.

At the top of the yard theres the sharp smell of fox shit. The second gates hard to see, concealed behind ragged bushes of sycamore and wild lilac, but I know its there, just as I know to avoid the razor wire that loops above it. The gate swings open. In front of me, flat and metallic, is the canal, reflecting the Mars-red glow of the city. I stare at it for a moment, my breath vaporizing, and wonder whether to fish right here. Its deep at this point, a great tank of water held between banks of Victorian brick. Opposite me, on the far bank, is the dark mass of a disused warehouse, rusted bars guarding its long-broken windows. At its base, as if awaiting collection from the towpath, stands an old spin-dryer. Everything about the place suggests neglect. And big pike thrive on neglect.

However, its not where Ive come to fish. Ive come to fish downstream of here, in a place Ive been tipped off about. My source is Dejohn. Most fishermen will tell you anything, just for the hell and the geniality of it, but Dejohns information is usually good. Aged fourteen and a habitual truant, he knows every inch of this stretch. Were not friends, exactly, but we talk.

I saw him a week ago at the Vale of Health Pond on Hampstead Heath. It was a Saturday afternoon, and the light was going. Dejohn had caught a small rudd and was using it as live-bait, illegally but excitingly drifting it across the pond beneath a fluorescent yellow float in the hope of enticing a pike. We swapped stories as usual and I told him that Id heard that someone had landed half a dozen jack-pike weighing up to six pounds from a barge on the Kingsland Basin in de Beauvoir Town. Dejohn mused on this for a moment and then said that hed heard second-hand, but he trusted the source about some bloke whod been drinking in the Pentonville Road and at closing time, well pissed up, had decided to go fishing. So hed hauled his gear out of the van, dragged it to the canal, set himself up with a dead-bait rig, and gone to sleep in his chair. At 3 a.m. hed woken up to find line running off his reel, and had struck into a big fish. When he felt the weight of it, Dejohn said and the dead, dour resistance of a really big pike is nothing like the angry jagging of a middleweight fish the hairs had gone up on the back of his neck. After a minute or so, during which the pike moved unstoppably upstream, the wire trace gave way and the guy was left there on the towpath, shaking like a leaf.

Now of course this story has all the elements of the classic pike myth. Its hearsay, its uncheckable, and it involves a monster. But to me it has the ring of possibility, being chaotic and unheroic, as these things often are. And Dejohn has been specific as to the location. Specific to the nearest yard. I move carefully downstream, watching my step in the near-darkness, past dim clumps of dead nettles and through a piss-smelling underpass. Distantly, theres the whisper of a sluice and the sound of swearing. Its a girls voice, probably one of the teenage prostitutes who bring their punters down to the towpath a cheaper if colder place to turn a trick than the local hotels.

Im out of the underpass now. Above me, against the dull red of the sky, stand the skeletal outlines of the St Pancras gasworks. Soon, my rod and tackle bags bumping against me as I walk, I come to a low bridge and push through trailing brambles into the tunnel. I can see nothing in the darkness except the faint red semi-circle of the exit, but theres an echoing drip and the stone slabs are greasy beneath my feet. When a truck passes overhead with a booming shudder the drips fall faster.

At the far end, as I step out into the ambient light, the towpath and the canal widen. At my back, behind galvanized-steel security fencing and a ragged thicket of wild buddleia, is some kind of electrical installation. A steel sign on the fencing warns of power-grid cables beneath the towpath. In front of me is a long oblong of water, perhaps twenty feet across. Its surface rocks like molten copper. There is no far bank, just a high wall of mossy brick, weeping with damp. As I lower my gear to the paving stones, the cold immediately begins to fold around me. This is the place.

I set up quickly, keen to get my hands back into my gloves. Im using an old fibreglass spinning-rod by Rudge of Redditch, heavy by todays standards but pretty much unbreakable. The reel, battered but well balanced, is an Aerial-style centre-pin. The baits are frozen sprats, mounted by a single treble-hook to wire traces. Pen-torch in mouth, I knot a trace to the fifteen-pound breaking-strain monofilament. A small coffin-lead goes between line and trace, to hold the bait to the bottom. Its the most straightforward rig possible. You dont want to get elaborate in the dark.

A final check. The red bulb of the pen-torch is bright enough to inspect the knots and swivels, but doesnt knock out my night vision. The landing net stands within reach against the bridge. The rod-rest is jammed securely into a crack between the glazed bricks at the towpaths edge. Stripping half a dozen yards of line from the reel, I send the sprat looping into the darkness. There is the faintest of splashes and I sense the coffin-lead sinking deeper and deeper, before, with a tiny slackening, it touches bottom. I reel in until the line is tight, engage the ratchet, lay the rod in the rest and sit down on my folding stool. Incline my back against the cold brickwork of the bridge. Wait.