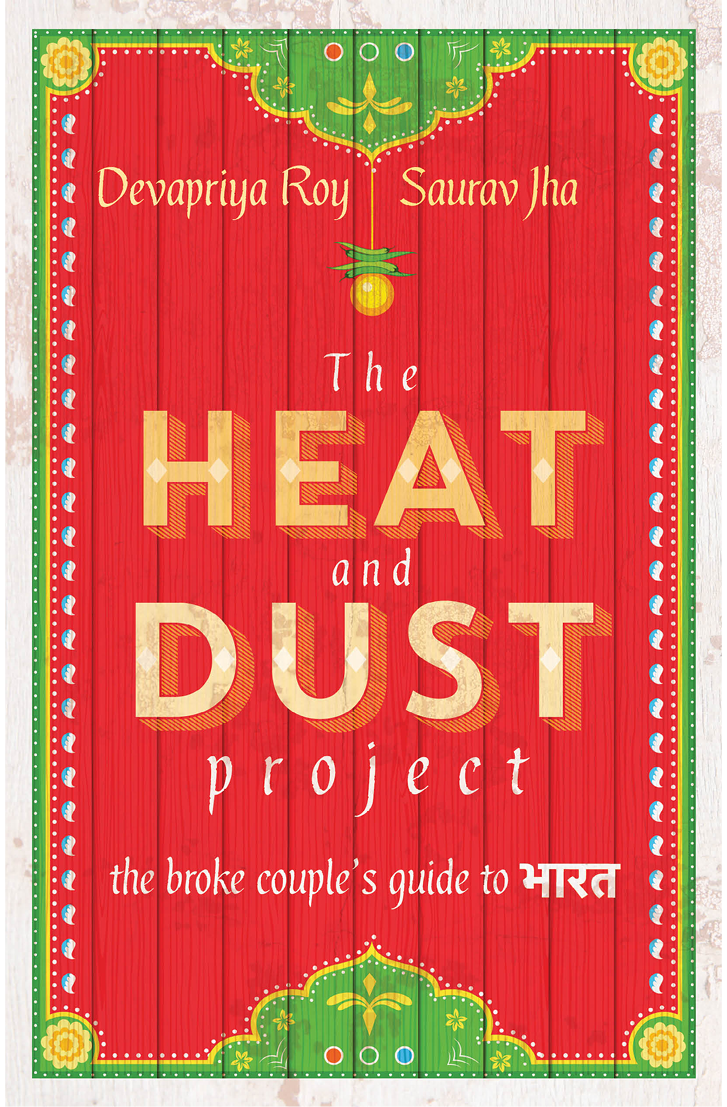

Cover

Title page

THE HEAT AND

DUST PROJECT

The Broke Couples Guide to Bharat

Devapriya Roy and Saurav Jha

Dedication

For

Meenakshi, who was born two weeks before the journey and was the fair star monitoring its mad course; Saksham,

who offered to write a part of the book (as long as

we helped with the spellings); and Priyanka, who heard all our stories first and is reading our books now.

Contents

In many parts of the world, there is something called a gap year. Not so in India. While young people elsewhere contemplate a gap year (amply aided by exchange rates), eighteen-year-old Indians of certain classes swot madly for entrance exams. It might not be off the mark to say that middle-class Indians truly peak in focus and ambition between the ages of sixteen and eighteen. It is great hormone management too in a way.

One hears of parents in the Western hemisphere who are mortally afraid that their childrens jobs are going to be Bangalored, outsourced to some briskly busy Indian IT professional who thinks nothing of working fifteen hours a day, every day. If he were to go back in time though, and see his seventeen-year-old version, and the sheer amount of effort he put into cracking the exams the ones that would morph him to the said IT professional well, hed have to confess he was taking it really easy at his fifteen-hour workday. Their kids, with all the cheerleading and prom and sex and protection talk, are no match whatsoever.

But, to cut a long story short, we did not come from a tradition of gap years, and now, past our mid-twenties, wed missed that age group by nearly a decade. We lived yuppie lives in the heart of Delhi. We had decent, soulless jobs. We even had a garret apartment in a lovely neighbourhood that would be filled, on certain mornings, so generously with the sun and the sound of children playing outside that it was easy to decide in favour of householding and consumption.

We were the usual: nine-to-sixers, investment-makers, mall-goers, office-trippers and city-slickers. We were life-going-to-seeders.

Then we came up with an insane idea.

Everyone thought we were mad to put all our eggs in one basket: the idea of a transformational journey through India. On a very, very tight budget. We went ahead anyway.

This book is the story of what happened then.

Devapriya and Saurav

Atha

(Here, Now)

T he bus is late. When we reach Jaipur, the touristy blue sky has begun to deepen incorrigibly. We hail an auto. By the time we get to the fork in the road it is the hotel district close to Mirza Ismail Road, fairly central dusk has leapt forward to night. Or perhaps, it is just the cold.

We know the first hotel at the mouth of the street: daintily designed and set back inside a little garden. It is quite expensive. (Wed stayed there once in the past and we couldnt afford the prices then either.) We walk straight past it and pop into the next reception. Prices at the second hotel, a functional-looking structure, start from a shocking Rs 1,200 plus taxes.

Outside, the lane is streaked with dim shafts of light leaking from hotel rooms on either side. We stop religiously at every hotel; ask the rates, the facilities. True to the project, we step out and sigh, suffering a curious mix of outrage and nerves at room rents. But it is day one it will not do to cave in already. It will not do to end up taking one of the better rooms with the promise of hot water.

Eventually, on to the last few deluxe 2-stars in that series. The character of the neighbourhood has changed perceptibly. We are now deep within the recesses of that rough mohalla, down a typical Indian lane which has seen several relayerings of asphalt over the years, but never once evenly and ugly rooms are freely available for 400 rupees. They are painted an unvarying dull off-brown, if there were such a shade. Their Indian-style bathrooms are streaked with old red stains, which, I can only hope, is paan. The straps of my backpack have begun to cut my shoulders.

At long last, the final hotel. A narrow building, terraced, with a name so elaborate that it sits off-kilter, almost wayward, on peeling walls: Hotel Veer Rajput Palace . We pause a moment to regroup.

Itll have to be this one, I guess, S says, almost relieved. Shall we try to settle at 300? I dont think theyll go lower than that.

I am exhausted. I cannot think of returning to any of the hotels weve just left behind. In front, where the block ends, there is simply a claque of dogs guarding the entryway into a dark by-lane of small unpainted houses. No hotels.

I nod and follow him up the three steps. The door is ajar.

Dear God, this parachute is a knapsack.

Chandler Bing, Friends

J anuary 2010: It is a foggy winter day in Delhi when it begins .

Dilliwalas will, of course, say that all winter days in Delhi are foggy. But on some days, like this one, the fog that is barely endured in the morning stretches well into afternoon making the city irritable and chilly, edgy with remorse.

Buses for Jaipur leave at regular intervals from Bikaner House.

It is about one-thirty now, midday, and we find ourselves rushing that way in an auto, unaccountably though, as there is no reason to rush. Not any more. We are or so we would like to believe free individuals. We have no bosses to report to, no landlords to be paid at the end of the month, not even a sad plant gathering dust at the office desk to chide us. We can, if fancy strikes, take a detour to Himachal Bhavan which is close by, take one of their buses and dash off to, say, Manali. I smile as I think this aloud, stretching my arms in an arch of delicious freedom.

We cant, S replies shortly. We have to stick to the plan. As it is, we are behind schedule. It takes a minimum of four-and-a-half hours to get to Jaipur, by when itll be evening. And then we will have to scout for a really cheap hotel. Dont imagine for a second that thats going to be easy. Its winter, high season in Rajasthan. Plus, he adds, as if this were a clincher, we dont have enough warm clothes for Manali.

Its not that I dont have appropriate answers to each of the above claims because I do (I always do) but, for now, I let it go. I busy myself checking if weve stashed our luggage alright. In addition to my cavernous canvas handbag, there are two backpacks one red, one black which wed bought in Calcutta last month for about 700 rupees apiece from a luggage store in New Market. There had, naturally, been posher brands in the shop. A remarkable rust-coloured Samsonite, for instance, with a thousand loops and discreet zips and dinky pockets. It was for 5,000 rupees. Hung in a special alcove in the shop, a thing of beauty. S didnt even allow me to go within sniffing distance of it. Spending one-tenth of the entire (proposed) budget on gear? Not on his watch, apparently.

While were on the subject, you might as well know there was a mighty row last night over the said backpacks.

To be honest, this is my first backpacking trip across India. Across anywhere, actually. So I did not want to take any chances with equipment. Given that we were to be gone for months, I came up with a pretty comprehensive list.

1.3 jeans (one could get wet while the other is dirty, in which case I would thank my stars that Id packed a third).

2. 9 8 7 6 t-shirts (they are ordinary cotton t-shirts v.v. light).

3.A couple of salwar-kurtas (we may be travelling through rather conservative places where it might be considered too firang to prance about in jeans; for fieldwork, for people to talk to us freely, we need to be discreet and fit in).

Next page