for Lily

CONTENTS

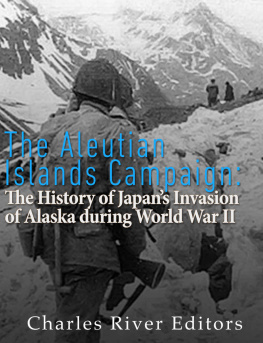

APRIL 1, 1943

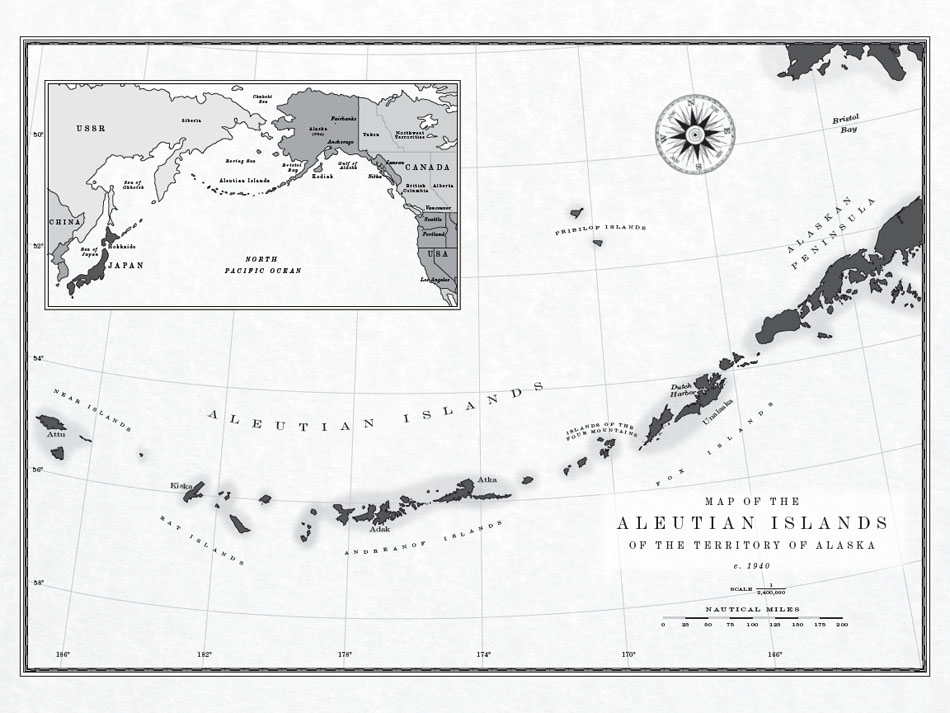

W HEN JOHN EASLEY OPENS HIS EYES TO THE MIDDAY sky his life does not pass before him. He sees instead a seamless sheet of sky gone gray from far too many washings. He blinks twice, then focuses on the tiny black specks drifting across the clouds. They pass through his field of vision wherever he turns to look. Last winter, the doctor pronounced them floaters. Said that by Easleys age, thirty-eight, plenty of people had them. Little bits of the eyeballs interior lining had come free and were swimming inside the jelly. What Easley actually sees are not the specks themselves, but the shadows they cast as they pass over his retina. To avoid their distraction, the doctor advised him to refrain from staring at a blank page, the sky, or snow. These are his first conscious thoughts on the island of Attu.

He sits up straight. When he does, it feels as if his head has a momentum all its own, as if it wants to continue its upward trajectory. A dull pain jabs his ribs. He places bare hands in the snow to keep from keeling over. The parachute luffs out behind hima jaundiced violation against the otherwise perfect white. Fog so thick he cant see the end of the silk. For a moment, he is anxious it might catch a breeze and drag him farther upslope.

Planes whine and circle overhead, unseen.

Easley flexes his hands. The gloves were ripped away by the velocity of the fall. He gazes down his long legs and moves his boots from side to side. He slides the flight cap from his head, runs fingers through his hair, checks for signs of blood. Finding none, he unclips the harness, rolls over on his stomach, pushes himself up. He is, unaccountably, alive and whole. And so it begins.

The fog is better than an ally; it is a close, personal friend. It covers his mistakes and spreads its protective wing over him, allowing him to escape detection. But it also separates him from the crew, if indeed anyone else has survived. Then a red flash of memory: an airmans lapel suddenly blooms like a boutonnire before the mans head slumps forward and lolls.

Not far downslope, the snow gives way to an empty field that spreads off into the mist. Yard-long blades of last years ryegrass are brown, laid flat from the full weight of winter. Easley returns to the parachute, gathers it up, hastily shoves it back into its pack. It does not go willingly. He hoists the pack onto his shoulders, winces at the pain in his side, then stands defiantly erect, wondering what to do.

The occasional report of Japanese antiaircraft fire begins to define space. Between distant burstsfive, ten miles?is the nearby cascade of breakers. But like staring into deep water, the fog misdirects, distorts. Within the hundred-yard range of visibility, there is no cover. He is fully, completely exposed. He unshoulders the pack and uses it as a seat.

He stares at the backs of his hands, which have gone pink with the cold. Lately they have been putting him in mind of his father. They are no longer the hands of a young man, clear and smooth. Suddenly it seems as if every pore and vein reveal themselves. A topography of thin lines and faded scars.

John Easley was all of seven years old when he let go of his brothers sticky hand in Londons Victoria Station. They had arrived from Vancouver, by way of Montreal, only the day before, destined to spend the next eight months in a tiny flat as their father advanced his engineering credentials. John would have responsibilities. For the moment, however, while their mother was off searching for a job and their father stood in line for tickets to the Underground, Johns only task was to remain on the bench and watch over three-year-old Warren. But those magnificent trains easing into and out of the station drew him like a spell. He is sure he had his brothers hand when he first wandered down the concourse, just as he knows that he was the one who let go.

The guilt came on like a fever. After all these years he can feel it still. He turned round, but the benches, the platforms all looked the same. There were numerous toddlers from which to choose, each firmly attached to other families. What started as a trot turned into a sprint, out of the station and into the conviction that it was already too late. Adrenaline gave way nausea, then dizziness overtook him.

He awoke to a ring of female faces and the vague idea that he had risen from the dead. But his father soon appeared, cradling his brother Warren, his face twisted and pale. He thanked the women and grabbed John by the upper arm. Once a discreet distance away from the scene, he set Warren down on the pavement, then turned to his eldest son. How could you leave your brother? Where on earth did you think you were going? Then, for the first and only time, Easley watched his father break down. Unwilling to let anyone see him cry, he reached up with both big hands and covered his face in shame.

Antiaircraft fire grows sporadic then stops altogether. The wind begins to stir. Easley rises and stares into the mist. He makes his way downhill two hundred yards, off the last patch of snow and onto flattened rye. The terrain, soft and spongy underfoot, slopes toward the beach. Not a single tree presents itself, no bush of any description.

A small stream bisects his path. Less than a yard across, it snakes through the weathered grass. Easley lies down on his stomach with his head above the water. He puts his lips to the cold little stream and drinks so deep his head begins to ache. When the pain subsides, he drinks again as if he hasnt seen water in days.

He pushes himself up and notices a glimmer in the current, a suggestion of reflected sun. A gust blows the fur-lined collar of the flight suit against his cheek, then lays it down again. The far-off scream of an arctic tern is followed, strangely, by what sounds like a cough. Easley spins around. He now has perhaps a hundred feet of visibility and that is improving rapidly. The farther he sees, the more he realizes how completely exposed he is. No stump or boulder to duck behind, no ditch to conceal him. His heart trips a beat. Easley strains to hear the cough again but detects only the breaking of waves. He stands with thumbs hooked in the straps of his harness, at a loss for what to do.

And then he turns to see a rift open up in the fog. Like endless curtains parting, the rift widens and moves his way, brightening the land, warming the air on approach. Finally, the sheet splits open and the sun spills down directly overhead. It is such a miraculous thing that he forgets, for a moment, that he is behind enemy lines.

The opening extends down the slope and onto the beach. He can make out the waves pealing white under pale blue sky. As the opening expands and liberates more and more terrain, Easley hears the faint cough again and stares through the vapor for its source. Unarmed, he can only watch as a form takes shape near the edge of the beach. Japanese? A member of the crew? It is clear that the man has seen him. Easley doesnt know whether to raise his hands or run.

The fog slips like satin from the slopes of a dormant volcano, revealing a frigid beauty. All is laid bare in the bold relief of the rare Aleutian sunpatches of white, tan husk of last years grass, blood blue North Pacific. When Easley recognizes the lone figure, he stifles the urge to shout for joy. He unhooks his thumb from the harness, raises his hand, and waves.

A fresh bust of antiaircraft fire and they both buckle at the knees.

Then, just as swiftly as it began, the fog stalls its retreat. Like a wave racing down a beach to the sea, it hesitates, reverses course, then comes flooding back again. They walk toward each other in the gathering mist, the preceding color and light now seeming like a dream. They approach each other with widening grins, like theyre the only ones in on the joke. And when they meet, they hug long and hard, like men who had cheated death togetherlike men convinced the worst is behind them.