To she who must be obeyed

A H ISTORY OF

H IGHWAY R OBBERY

D AVID B RANDON

First published in 2001

This edition published in 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL 5 2 QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

David Brandon, 2001, 2004, 2010, 2011

The right of David Brandon, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6820 4

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 6821 1

Original typesetting by The History Press

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

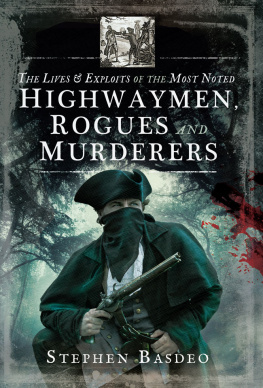

W hy is the highwayman perceived as a romantic and glamorous figure? Why have heroes been made out of men who were violent bandits and sometimes murderers and rapists as well? This book attempts to move towards an explanation by examining the activities of some of the best-known highwaymen in England and by trying to describe highway robbery while placing it in its social and economic context. Unlike most other works, it examines highway robbery generally, not just the activities of highwaymen. It covers the period from medieval times to the 1860s, when the citizens of London went in fear of being attacked and robbed by the dreaded garotters.

Mention the word highwayman and everyone has the image of a masked, caped, tricorn-hatted, cavalier-like figure astride a handsome roan, moving out of a wayside thicket, pistols at the ready and uttering the immortal command, Stand and Deliver!. His victims, at least in popular mythology, are well-to-do travellers in their own carriages, on horseback or being conveyed by stage or mail coach. The travellers include a damsel of bewitching beauty who goes into a dramatic, well-timed swoon on catching sight of this menacing yet tantalising robber. The myth continues. The highwayman, because he rides a horse, is likely to be a gentleman by birth. He is gallant and considerate towards his victims, as any gentleman would be. Rumour says that he donates some of the proceeds of his robberies to the districts most needy citizens. Fashionable and wealthy ladies intercede in court on his behalf when he stands trial and visit him in the condemned cell, fulfilling their own fantasies and providing some last-minute succour to the still defiant miscreant about to embark on his awful last journey.

Highwaymen feature in countless folk-tales and ballads, nearly always cast in this kind of romantic light. Novels, plays and films have consistently placed the highwayman in the role of hero, as a dashing gallant or at the very worst, a likeable rogue. Similar adulation is not extended to other highway robbers such as footpads, pickpockets or those now called muggers. How often do we hear of popular songs celebrating the activities of other members of the criminal fraternity such as pimps, embezzlers or burglars? The reality is that many highwaymen were ruthless cut-throats who had no intention of disbursing the proceeds of their robberies to the meek and needy. For such people they had total contempt. They could stay where they always had been, down at the bottom of the social hierarchy. Meanwhile, fortune favoured the bold and so the highwayman grabbed whatever he could and did so totally without scruple or concern for his victims.

The received wisdom that sees crime as antisocial and deviant sheds little useful light on how the common people saw the activities of reprobates like highwaymen. Neither does it illuminate popular perceptions of the nature of criminal activity and of the role of the authorities in attempting to maintain their law and order, their property and privileges while all around them large sections of society went without many of lifes necessities. The helpful concepts of social crime and the moral economy were developed by historians such as E.P. Thompson in the 1970s. They denoted the kind of illegal activity that, even if not intentionally, represented a challenge to the status quo and may have enjoyed considerable support from the mass of the population. Most people warm to Robin Hood whenever he gets one over on corrupt and greedy people like the Bishop of Hereford or the Sheriff of Nottingham. Here is the folk-hero, popular because he cocks a snook at those in positions of power and wealth thereby helping to undermine a status quo that the common people know is deeply flawed. Smugglers and poachers are other criminals whose activities have enjoyed widespread popular approval. The social crime concept goes some way towards explaining the selective and irrational nature of popular attitudes towards the different kinds of criminal activity. It is hard to believe, however, that many highwaymen saw themselves as striking a blow against social injustice. The highwayman was there for the money. Many also enjoyed the excitement and the notoriety.

The highwayman may personify some of the aspirations that lie, often well hidden, in most of us. He is a freebooter, a libertarian, a devil-may-care individualist who scorns stifling conventions. Not for him the crushing tedium of a life of diligent but unrewarding toil. His purpose in life was to fill his belly and acquire enough money to enjoy the good life whoring, gambling and drinking with little thought for the morrow, and to do so at the expense of others who may have worked hard for what little they had. In reality the highwayman was a very unlikeable character whose intentions differed little from those of the basest cut-throat or pickpocket also out on the road. For that reason it is hard to grasp why he seems so greatly to have endeared himself to the public.

It undeniably took courage to hold travellers up and highwaymen needed to exude confidence as well as an air of menace and ferocity with which to browbeat their victims. Force of personality could help to avoid the use of physical force. The job required superb horsemanship and stamina because of the need to be out in all weathers and perhaps to ride pell-mell over long distances when being chased. Patience was also needed because the highwayman might wait hours for a suitable opportunity whereupon he would suddenly leap into violent and possibly hazardous action.

Society might have felt some sympathy for the dashing but demobilised cavalry officer after the English Civil War and excused his taking to highway robbery because he had no other useful skill. They did not feel equal compassion and toleration for his subordinate who was a robber on foot, a footpad, a pickpocket or other street nuisance. The highwayman therefore occupies a unique and somewhat contradictory place in that collective consciousness called history.

What kind of society is it that provides the conditions in which highway robbery can thrive? It has flourished in this country at times when the hold of government and of law and order has been tenuous and incomplete. However, society will not have been in a state of complete breakdown, because a prerequisite for the robber was a supply of travellers, preferably affluent, and that required at least some degree of political stability and economic prosperity. Such a situation was to be found in the England of the fourteenth century, frequently wracked by internecine struggles between king and nobility and among the nobles themselves. However, in spite of political and social instability, the countrys trade and commerce were growing and there were abundant pickings along the highways for the bold opportunist. Likewise, in the middle of the seventeenth century the Civil War disrupted the tenor of government but continued economic expansion saw traffic on the roads running at unprecedented levels. A factor that partly helps to explain the public perception of the highwayman is that he frequently operated at times when the forces of government were unpopular and enjoyed no real legitimacy. This made it easy to transform a brutal bandit who was handsome, mysterious, rode a fine horse and was outside the law into a popular hero.